SECTIONS: 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 19 | 24

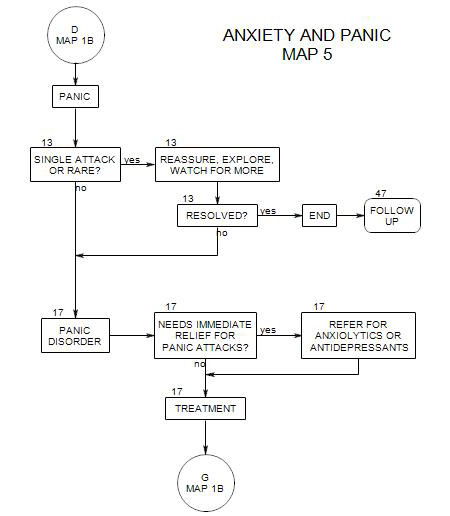

- Appears on Map 5; follows Section 13 on Map 2

A person is said to have a panic disorder when he/she has a series of panic attacks that can’t be attributed to another anxiety disorder or to a medical cause. This definition emphasizes the idea that in some cases another disorder can be primary, and once it is treated, the panic attacks may stop. An alternative view would be that other causes should be sought, but in the meantime, the panic should also be treated as primary.

Typically such a series of panic attacks will be accompanied by-

- worry about having another attack.

- fear that the next attack will lead to loss of control, a heart attack, etc.

- a significant change of behavior related to the attacks.

It may be helpful to consider the disorder as having three components: [1] spontaneous panic attacks. [2] anticipatory anxiety about places or situations associated with the attacks, and [3] phobic avoidance of those places or situations (Hollander, Aronowitz an Klein, 327). Treatment should be planned to deal with each aspect.

Treatment should begin as soon as possible, because of the degree of the person’s discomfort and fears of another attack.

17a First Step: Reduce the Power of the Panic Attacks

First, you should eliminate the panic attacks or reduce them substantially, because these typically are your patient’s greatest concern. (Preston, O’Neal and Talaga, 2002, pp. 109-111; Mavissakalian and Martin, 1997, pp. 196-7) Refer him/her to a psychiatrist or other physician for-

- high potency benzodiazepines, such as Xanax [Alprazolam], Klonopin [Clonazepam], or Ativan [Lorazipam] for immediate control of the panic attacks and anticipatory anxiety.

- beta blockers, to reduce physical symptoms temporarily.

- antidepressants [except for Wellbutrin, which may exacerbate panic attacks] for longer term control. It may be important to introduce an antidepressant early on, if the patient is discouraged and has suffered loss of self esteem.

17b At the Same Time, Gather Information About the Attacks

You can think of a panic attack as a kind of explosion of the person’s autonomic nervous system, producing the symptoms listed in Section 13. There are several possible paths to a panic disorder.

- The symptoms can be the result of a medical disorder.

- The person can have an autonomic dysfunction that has been exacerbated by stress.

- The person can have a mild imbalance and can be experiencing a lot of stress.

- Note that there is a risk of overinterpreting a patient’s avoidance behavior or failure to “understand”. It can be a mistake to attempt to uncover unconscious sources before the patient is ready.

You should gather background information about recurrent patterns of antecedents:

- events that could have set the stage for a panic disorder. Look for stressful life events and ongoing stressful conditions.

- events at the beginning of the series of attacks.

- triggers for particular attacks, including thoughts, places, activities.

- anticipatory anxiety and the avoidance of situations that have led to panic attacks.

- symptoms and thoughts during attacks- especially: what the patient imagines will happen as a consequence of the attack.

- details about the first attack, including the date and time, place, immediate context, and general stress level at the time.

Explore precursors and preconditions, such as-

- anxiety sensitivity. People with panic disorder may be extremely sensitive to anxiety, and prone to an extreme reaction.

- a catastrophizing cognitive style.

- habits of avoidance.

- dependence on others.

- a strong need for safety and security.

- a history of soft signs of autonomic system dysfunction, including blushing, wet or cold hands, faintness or palpitations (Roberts, 1984, p. 415).

Ask about medical disorders that could cause symptoms that lead to panic attacks:

- Mitral valve prolapse

- Hypoglycemia – here, inadequate brain sugar leads to a rapid uptake of adrenalin, which raises sugar levels but also produces panic symptoms.

- Hyperthyroidism

- Hypoparathyroidism

- Cushing’s syndrome

- Pheochromocytoma

- Temporal lobe epilepsy

Explore long-term consequences of the attacks, including-

- coping behaviors: things the person does to reduce or alleviate the attacks. This might include avoidance of places, thoughts, or activities; or ritual behavior; or self-medication of some kind.

- the person’s cognitive style, especially if it is rigid or extreme relative to the symptoms. “I can’t let myself feel any anxiety.”(Wilson, 1996, pp. 263-266)

- possible sense of hopelessness (“I’ve tried everything, and nothing helps.”).

- possible effects of the attacks on the person’s self-esteem. ( “I can’t deal with the world.”)

- shame regarding the inability to cope more effectively.

- depression.

- risk of suicide, possibly as high as 20% (Weissman, etal., 1989).

Ask about causes of the attacks. People will often have ideas or theories about the reasons for their attacks, and they could be right. But even if they are wrong, their ideas could be useful. For example, if a person’s theories involve paranoid delusions, such as being singled out and attacked by terrorists using radio transmitters, etc., then it becomes at least equally important to treat the paranoia.

Ask about the patient’s attempts to treat or manage the panic, including use of alcohol, marijuana cocaine, or other drugs.

If the person was afraid of a medical disaster, such as a heart attack, then ask if he/she consulted with a physician or went to the emergency room. Ask if tests were done, and if so, what the tests showed. If necessary, get a release, and contact the patient’s physician or hospital.

It may be helpful to watch for other issues in people with panic disorder. If they occur in a particular patient, they may become useful directions for treatment to pursue, whether they are antecedents or consequences of the disorder. They could include:

- poor physical and emotional health.

- alcohol and drug use.

- marital issues.

- financial issues.

- poor social functioning.

- prior suicide attempts.

17c. Formal Diagnoses

Consider the following:

300.01: panic disorder without agoraphobia

300.21 panic disorder with agoraphobia

17d. Provide Information about Panic

Along with gathering information, this can be a good time to provide information about panic attacks: what is typically involved, what the person can expect with or without treatment, anticipated side effects of medications, etc.(Carmin and Pollard, 1996, p.59; Hollander, Aronowitz and Klein, 1996, p. 327). Additional psychoeducational work may be helpful at various times throughout treatment.

THE COURSE OF AN ATTACK

The symptoms of a panic attack can be described as follows:

- It starts with a sudden and apparently unprovoked attack of fear.

- This leads to a burst of adrenalin, our normal way of preparing to cope with danger.

- Adrenalin causes rapid breathing, increased heart rate, and sweating. We are ready for either fight or flight.

- If you neither fight nor flee [for example, you might be standing on line at a supermarket] rapid breathing leads to more oxygen and less carbon monoxide in your blood.

- This in turn, can cause symptoms of lightheadedness, dizziness, and tingling or numbness.

If the symptoms persist, they may intensify, as you recognize each of them and become frightened about what might be happening to you.

SOME THEORY AND IMPLICATIONS

Many professionals now believe that panic disorder is at least partly caused by autonomic system dysregulation, and that the surprise of an attack can be due to their being little direct central nervous system [esp: conscious thinking] involved. However, an attack may occur in times of overall increased stress, and a person’s thinking may have a lot to do with his/her stress level or interpretation of stress.

This leads to some treatment implications:

- Trying to understand the psychological meaning of the attack may be wasted effort. The attack may not harbor a lot of meaning.

- There is a strong possibility that a physiological or neurological process is contributing to autonomic stress.

- Medical diagnosis is important and has a better chance of uncovering underlying causes for the panic attacks than psychological exploration.

- Medication can relieve symptoms temporarily, but it is unlikely to have a permanent effect. Even if medications stop the attacks, discontinuation of the medication is likely to be followed by their recurrence.

- The person may be under a lot of stress, including anxiety or depression. The anxiety, depression and environmental stress may be amenable to exploration.

- The patient’s thoughts are consequences of the attacks, not the cause of them. The thoughts can be explored fruitfully, however the patient’s interpretations may be associational: “It felt like a heart attack.” ,may mean, “the symptoms remind me of symptoms I associate with heart attacks.”

- Psychological treatment can be directed to any underlying psychological stress that the patient may be experiencing, as well as to the patient’s interpretation of the symptoms.

- Many patients can expect that there will be no cure, and that similar autonomic flare-ups will recur. It is possible that, if the panic attacks can be recognized as physiological reactions without deeper meaning or implication, they can be accepted and managed more effectively.

17e Deal With Comorbid Conditions

The patient may have reacted to his/her panic attacks in a variety of ways, in attempts to avoid them, to understand them and to control them. Reactions can include…

- depression from feeling helpless to prevent the attacks and from the limitations that the attacks have imposed on the person’s life.

- substance abuse from attempts to treat the fears or depression.

- phobias, possibly as a background condition for panic attacks or as a consequence of generalization from panic attacks to the conditions under which the attacks have occurred.

- agoraphobia, [ Section 21 ], which can occur in either of two ways: [1] from associating attacks with specific places or events; and [2] from associating certain activities [aerobic exercise, sauna baths, scary movies, caffeine, sex, etc.] with internal cues experienced during panic attacks. (Mineka and Zinbarg, 2006, p. 16)

Alternatively, other conditions may have made the person more vulnerable to panic. Whichever the direction of causality, these comorbid conditions need to be addressed (Preston, O’Neal and Talaga, 2002, pp. 110-111, Mineka and Zinbarg, 2006, p. 16):

- For example, post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD] [see Section 9 ] includes symptoms that can lead to panic attacks: chronic tension, loss of sleep, ruminations about the traumatic event or events, re-living them, fear of recurrence, lowered self esteem.

Early on, a decision must be made relative to other condition[s] – whether they should be addressed first, concurrently with treatment, or subsequent to it.

17f. Ongoing Data Collection

In addition to gathering information in session about the person’s symptoms, it can be very helpful to track them throughout treatment (Hollander, Aronowitz and Klein, 327) by having the person keep a diary to record avoidances, anticipatory anxiety and actual attacks. This has the benefit of allowing evaluation of each aspect of treatment, especially should the patient doubt the effectiveness because of persistent anticipatory anxiety.

Part of the patient’s process of avoiding threatening situations and thoughts may involve trying not t0 think about them or working to remember them, once they are past. For this reason, recollection of prior panic attacks may be incomplete or distorted. Some people may not want to talk about panic attacks, either because they are too frightening or because they are afraid of precipitating one by thinking about it. You may need to reassure the person that thinking about an attack won’t bring it on. With some patients, you may challenge them to bring on an attack, as a demonstration that thinking about it won’t make it happen.

As part of the work, ask the person to carry a notebook or other way of keeping a record. Then following any attack, he/she can make a record of each of the above considerations [triggers, anticipatory anxiety, thoughts, coping behaviors], for processing in therapy.

17g Cognitive Therapy

Cognitive treatment [ Section 29 ] is designed to work with the conscious thoughts and thought patterns that lead a person to expect the worst.

- It can address the logic and consistency of the accompanying thoughts [cognitive], together with providing alternative cognitions that undermine the panic-inducing thoughts. (Hofmann and DiBartolo, 1997, 57-82)

- It can also address the thinking that infers catastrophic consequences from internal sensations and lead the person to attribute the sensations to normal body processes. (Barlow, 1988, p. 451; Carmin and Pollard, 1996, pp. 62-64).

- Patients can be helped to work out the likely consequences of their expectations and test them against actual events. Then they can be helped to generate other reasonable hypotheses and compare outcomes.

- Patients can be encouraged to identify and recognize negative thoughts and use “thought stopping” [which consists of saying “STOP” or the equivalent, sometimes out loud, when they catch themselves thinking that way, and then deliberately thinking something else, or changing focus to their immediate environment.] Simple as this reaction may seem, and difficult as it may be to carry out consistently, many patients are able to use it effectively.

17h Work Directly on the Internal Sensations Accompanying the Attacks

Barlow (1988, p .451) and Carmin and Pollard (1996, pp 64-66) recommend direct, systematic exposure to the internal symptoms of the panic attacks, by generating those sensations in controllable ways, and in the relative safety of the therapy setting. The goal here is to separate the physical symptoms from ideas of physical and emotional disaster.

- Have the person exercise to stimulate cardiovascular symptoms. Running in place, stair-stepping, etc. will work here.

- To simulate the respiratory symptoms of a panic attack, the person can voluntarily hyperventilate, hold his/her breath, or breathe through a straw.

- Having the person tighten the intercostal muscles simulates tightness in the chest that may be interpreted as an impending heart attack.

- Induce dizziness to replicate lightheadedness by having the person turn in circles or spin in a chair.

- Cause shakiness by having the person tighten the muscles of his/her arms or legs for an extended period of time.

In addition to demonstrating that the symptoms of a panic attack are easily generated, you can help the person work on controlling the symptoms as they arise.

Breathing exercises [ Section 37 ], especially slow, deep breathing, can help deal with respiratory symptoms and give a sense of self-control.

Relaxation training [ Section 31 ] can help with all of the symptoms involving muscle tension. The goal here is to be able to relax at will, and undermine the second phase symptoms.

Autogenic Training [ Section 32 ], because of its focus on physical sensations, can provide an opportunity for a patient to experience some of the internal cues of a panic attack in a relatively safe setting. This can offer an opportunity to explore the sensations and gain some control over them. At the same time, the experience can lead to exploration of the meaning of the sensations in dynamic therapy ( Section 28 ). See also Linden and Lenz (1997, p. 148)

17i. Adjunctive Treatment [see Section 30 ]

If medications are chosen for extended use, antidepressants can be helpful (Mavissakalian and Ryan, 1997, p. 184), because they reduce anxiety and are not physiologically addictive. Antidepressants can also be effective with both stress-inducing primary depression and with depression that many patients experience as a consequence of feeling damaged and out of control from repeated panic attacks.

Benzodiazepines may be the medication of choice for long-term management. The recommended dosage is low, and the side effects are minimal; and many panic disorder patients are able to lower their doses over time.

17j. Deal with Avoidances

Panic attacks are inherently frightening, and people naturally try to make sense of them and avoid having more in the future. It is normal to seek causes in the places that the panic occurs, the events, people or thoughts that were occurring when panic occurred in the past.

Over time, a person may learn to avoid the objects of situations associated with panic attacks. This can lead to a specific phobia – of dogs, gatherings, driving on the highway, standing on line in supermarkets, etc.

If panic is associated with several different situations, a person may infer that it isn’t safe to leave home, and develop agoraphobia; see Section 21. If nothing works, a person may become depressed about his/her ability to manage, lose self-esteem, despair, and possibly suicide.

17k. Issues for Dynamic Therapy

There are a number of issues that may have laid the groundwork or served as precipitants for panic attacks. These can be explored therapeutically and their power lessened through better understanding.

- Explore their sources, in the patient’s personality structure and interpretations of situations and events. (Almond, 1997, pp. 151-174)

- Long-term antecedents of panic attacks may include experiences that lead a person to feel helpless and vulnerable. (Mineka and Zinbarg, 2006, p. 17)

- Major losses may have left the person feeling weak and helpless.

- Other life changes can impact on the person’s stress level.

- Look for an early history with uncontrollable stresses or chronic illnesses that may have made the person vulnerable to heightened anxiety and fear. It could include a history of early separation and loss, early separation anxiety, or school phobia.

- Parents and other models may have prepared the person to expect disaster.

- Observing pain and suffering in others may have led to a sense of vulnerability and the inevitability of pain.