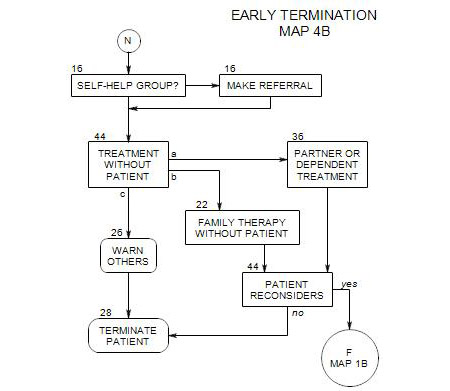

This section follows Section 6, and refers to a physiologically dependent person who is in serious danger to self or others but refuses detox.

An intervention is a procedure designed to convince a person in denial of the necessity for inpatient treatment. It is a way of dealing with a person who is in desperate need of treatment and also in the precontemplation stage [Section 40]. The person is a danger to him/herself and others but can’t or won’t see that there is a problem.

Before Vernon Johnson invented the Intervention in the 1960’s, it was commonly believed that an alcoholic person had to “bottom out” [by becoming so miserable from the consequences of his/her drinking that he/she could no longer deny how bad drinking was] before he/she would be psychologically available for sobriety.

Part of the rationale for having an Intervention is to help the alcoholic become aware of the consequences of his/her behavior before losing his/her job, killing someone in an auto accident, being divorced by a spouse, or causing some other disaster.

The goal is to convince the person that his/her alcohol misuse is harmful and that it is now time to get help and stop drinking. A successful outcome of this procedure results in immediate hospitalization.

There are at least three ways to have an intervention:

- individually

- Johnson or Minnesota model

- family treatment model

Of these three, informal interventions are probably the most common, Johnson Interventions are the best known, and family treatment interventions are gaining interest.

13a. Individual confrontation

Probably the most common kind of intervention occurs when a single individual in the patient’s life confronts the patient about his/her drinking and its consequences. The meeting is typically private and may not be discussed by either person after it happens. The other person could be a friend, employer or family member who knows the patient well and is prepared to speak forcefully. In many cases, the other person is also prepared to apply sanctions if the patient refuses to begin treatment immediately.

While such confrontations typically occur without professional consultation, it can be valuable for a therapist to guide the confronting person, to help the meeting be both supportive and forceful. Some therapists who specialize in interventions offer consultations for this type of confrontation as well.

13b. Johnson Institute or Minnesota Model Intervention

This is the kind of Intervention most often mentioned fro dealing with physiologically dependent patients who are “in denial” or refusing to admit the severity of their issues with alcohol.

In this case, a specially-trained therapist meets with the person and any number of relevant family members, friends, and/or significant others, for a forcefully confrontational session that may last from several minutes to several hours.

Most desirably, it occurs in the patient’s natural environment, such as his/her home, but it could be conducted in a professional office or other setting when the natural environment is not available.

The confrontation is a surprise to the alcoholic. It is arranged without his/her knowledge and he/she is typically misled about the way the upcoming time will be spent. What he/she expects to be a party, meeting, family gathering, etc., turns out to be an event where he/she is the center of attention of everyone there and unable to leave until each of the others has spoken. The others have been prepared in advance for a carefully scripted event that is difficult for the alcoholic to avoid or deny. The shock and social pressure are intended to drive the person to realize his/her impact on others and his/her own life, and to accept the necessity of immediate hospitalization to deal with the problem.

An Intervention was originally designed to confront the alcoholic in a forceful but sympathetic and non-confrontational way [Johnson, 1980]. However, such confrontations can become combative and critical, depending on the leader’s approach and the reactions of the patient and of other family members.

13c. Other forms of intervention

There have been at least two additional criticisms of the Minnesota Model:

- It assumes that only the alcoholic has a problem, whereas the alcoholic’s drinking may be expressing something about overall family dysfunction. In this case, to single out the alcoholic person is not only unfair but ineffective.

- Once the alcoholic is in an inpatient facility the job is assumed to be done, whereas treatment involves a long-term commitment going far beyond detox and rehab and requiring an extended commitment from others in addition to the patient.

The Systemic Family Intervention Model© [Raiter, 2006] focuses on the entire family, rather than the one alcoholic person. Other family members also need help, and the entire family system should be addressed.

An extended workshop is offered to the family, including information about addiction and its effects. The roles of all family members are examined, the ways that others enable the alcoholic, and alternative reactions that could be more effective. The alcoholic’s drinking is seen as symptomatic of family dysfunction. If he/she chooses not to attend the workshop, the leader and remaining family members hold it without him/her. The goals include re-structuring the family and changing the roles, reactions and communications of all family members. If the family no longer supports the alcoholic’s drinking, he/she must change as well, whether he/she participates in the intervention or not.

The ARISE model [Landau and Garrett, 1986] offers a graded series of interventions, from less intrusive to one similar to the Minnesota Model.

- In an initial phone call, a coach gathers information from one family member about the family, the patient, and the patient’s treatment history. During the same call, an evaluation interview is scheduled for the patient’s network of family and involved friends.

- At the evaluation session, information is gathered about the problem from all who participate. Plans are made for treatment for the patient and future meetings of the network.

- If the patient fails to enter treatment within a reasonable time period, a Minnesota-style intervention is planned and held, to pressure the alcoholic into treatment of apply sanctions if he/she still refuses to go.

13d. Deciding about having an Intervention

Reasons to have an intervention include

- the patient is at serious risk to self and/or others. [ See Section 6 and Section 26. ]

- he/she refuses to go for detox

- there is a good chance that he/she will respond to social pressure by going to the hospital (and not just dismiss everyone else’s testimony)

Reasons not to have an intervention may include

- absence of people who will participate (possibly because he/she has no close friends or family, or because co-workers are afraid of him/her)

- the patient’s expected lack of responsiveness (he/she is a schizoid, a sociopath, stubborn, or for some other reason)

- that it isn’t needed, either because the patient will go for treatment willingly or the reasons for insisting are insufficiently urgent.

- that the risk of failure is too great. This may especially be true when the intervention is a surprise and the family is already torn by the patient’s drinking or other issues. It may also be true if the patient is strong enough or detached enough simply to leave the intervention without listening.

- that the patient is someone who will comply with the social pressure by going to detox but most likely will not follow through afterwards and will return to drinking immediately.

- costs. An intervention can cost between $2,000 and $10,000 and require a great deal of coordinating and time involvement from family members. These issues must be weighed against the risks and costs of continuing without a dramatic change.

13e. Who Should be Involved?

A one-on-one confrontation should be handled by someone with credibility, personal strength and real power to affect the person’s life.

A formal intervention should be organized and run by a substance abuse professional who is experienced in the procedure, to ensure that it is carried out effectively. The participants should be people who are important to the patient and who are prepared to stand up and confront him/her about his/her behavior and its implications. They need to know the patient well and have meaningful relationships with him/her. Family members, friends and employers can all be helpful. The more participants there are, the better. The more unified they are in wanting change, the better.

13f. Preparations for a formal Intervention

Preparations include meeting with the significant members of the patient’s network in advance to plan the intervention, developing a list of issues related to alcohol misuse, deciding on a time, getting the person and others to the meeting place, and making sure of the availability of inpatient care. Inadequate preparation relative to any of these issues could lead to failure, and the opportunity could be lost.

Timing is extremely important. The critical participants [including the leader] need to be available at the time of the intervention. The patient should be sober [This might mean having it early in the day]; and ideally the intervention is timed to follow an alcohol-related problem, [such as an accident, an angry confrontation or fight, a blackout or time of confusion, a failure to carry out responsibilities, etc.].

Participants in a Minnesota model should be prepared to carry out their parts in the intervention. They should be

- factual and detailed about the patient, his/her actions, and the consequences of those actions to him/herself and others.

- able to express themselves with appropriate feeling. The lead may be given to those who can be forthright and emotional in their presentations.

- caring – not trying to punish or humiliate the patient, but rather to help him/her deal with a difficult disorder.

- prepared to stand up and confront the patient about his/her behavior.

- prepared to insist that the patient make an immediate change.

- prepared to state consequences for not changing and to carry them out.

Participants in a family model intervention need to recognize that they are involved in the problem and its solution, rather than being dedicated to blaming the patient for all that is wrong.

13g. Immediate follow-up

If the initial goal of the intervention is to get the patient into detox, then someone should have contacted facilities and made arrangements for the patient to be treated. His/her personal effects should be packed and ready to go, and someone should be available to get the patient to the facility as soon as he agrees and the intervention is concluded.

13h. Long-term follow-up

Preparations for an Intervention should not stop with getting the person into a detox facility, or even detox and subsequent rehabilitation. It cannot be assumed that a person who begins treatment will continue it, especially if the person has been coerced into it. Rehab facilities are filled with people who are only waiting to get out so they can drink again.

It is extremely important that plans for continued treatment are in place before the person is released from rehab, including return to therapy, self-help meetings and continued family involvement.