37. PSYCHODYNAMIC THERAPY

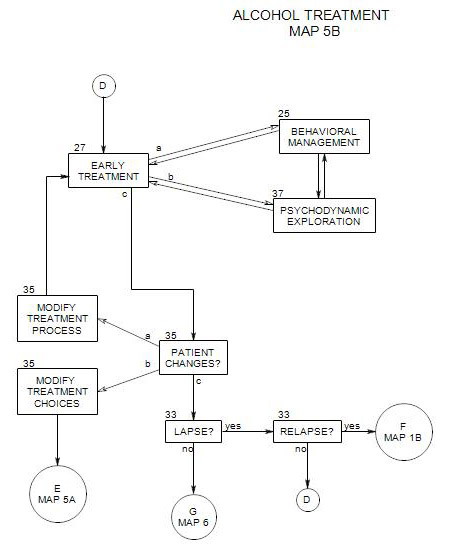

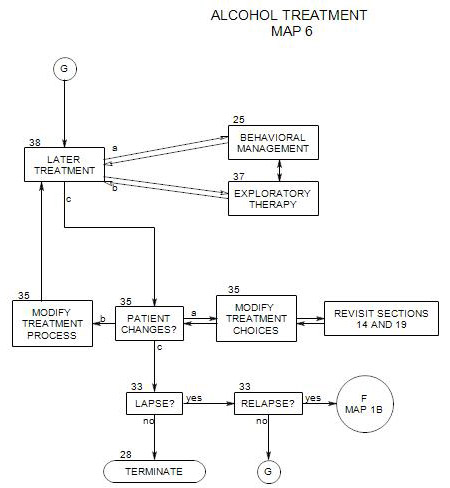

- This section coordinates with Section 27: Early Ongoing Treatment, Section 38: Later Ongoing Treatment, Section 25: Behavioral Management and Section 35: Change

Psychodynamic therapy can take on several functions, including –

- helping the patient adjust to treatment;

- addressing defenses that either support or undermine alcohol use;

- dealing with issues that may contribute to the need to drink;

- helping the person stabilize and improve his/her internal consistency and relationships with other people; and

- helping to manage or resolve other psychological issues or disorders.

Its focus is on the patient’s intrapsychic functioning, as opposed to behavioral management, which aims to help the patient gain control over his/her behavior and environment.

This section can only be suggestive of possible directions for therapy to follow. Additional help can be found in Section 34 and more extensive treatments of the topic in psychotherapy texts.

This aspect of treatment assumes that a large portion of a person’s thinking happens outside of awareness: that he/she is affected by unconscious motives and conflicts, and that the person’s awareness may be distorted in a variety of ways. A person may also have cognitive deficits and interpersonal misunderstandings due to unconscious conflicts and personal history. Part of the work of treatment is to understand, uncover, and unravel any intrapsychic and interpersonal issues that lead to difficulties in dealing with self and the world.

Psychodynamic therapy can be either more supportive or more exploratory. In exploratory therapy, the process focuses on uncovering unconscious material, which then can be evaluated consciously and loses some of its power to control the person. However, a search for unconscious material with active or newly recovering alcoholics can be destabilizing, both because the material uncovered has the potential to be psychologically threatening and because the common techniques for searching are themselves stress-inducing.

In supportive therapy, there is greater focus on strengthening ego functions, establishing psychological homeostasis and improving adaptation. The therapist is more real and open, and the work needs to be practical, immediate and cooperative.

Early on in treatment, supportive therapy is more helpful because the patient needs to stabilize and adapt more effectively.

However, exploration can happen within a supportive approach, and the patient can still uncover material that was previously out of awareness. Some of that material can be useful in moving him/her to greater self-awareness and more effective adaptation. This can happen in a variety of ways, including the examination of the idiosyncratic meanings to the patient of events, symbols, objects, people, actions, and so on. Sometimes, an examination of the meaning of an event can lead to a better understanding of the patient’s reaction to it. This in turn can lead to other associations and recollections, similar events in the past and so on. The extent of the associational train may need to be controlled, however, if there is a chance that too diligent pursuit of it could neglect to address the person’s drinking or could increase intrapsychic stree and lead to an increased need to drink.

Later, when the patient is more stable and the threat of relapse is reduced, it may be possible to work in a more exploratory manner. Then more traditional psychodynamic approaches can be of greater benefit – exploration of dreams, working with the transference, examining object relations and so on [see Kaufman, 1994, chapter 7].

Parts of this section include

- Supportive psychotherapy

- Adapting treatment to the patient’s stage of change

- Working with transferences

- Working with denial and other defenses

- Strengthening ego functions

- Exploring reactions to life events and situations

- Exploring triggers

- Examining the consequences of drinking

- Finding alternatives to drinking

- Treatment of other disorders

- Other common psychotherapeutic issues

- Dealing with lapses and anticipating relapse

37a. Psychodynamic Supportive Psychotherapy

Although some alcoholic patients may eventually be able to benefit from conventional psychodynamic therapy or psychoanalysis, most will not; and it is not generally effective to attempt treatment whose primary purpose is the uncovering of unconscious conflicts with any patients in early recovery.

However, psychodynamic supportive therapy involves a wide range of related techniques, designed to improve a patient’s ego functions and provide for better adaptation. that can be helpful with patients in early recovery. These have been described by Rockland [1989: pages 84-98] They include..

- encouraging the therapeutic alliance by emphasizing the cooperative aspect of treatment

- furnishing reassurance and hope

- giving suggestions and advice

- accepting abreaction

- giving encouragement and praise

- making prohibitions and setting limits

- emphasizing strengths and talents

- making clarifications

- using confrontation

- furnishing a model for identification

- strengthening adaptive defenses and undermining maladaptive ones

- supplying inexact or partial interpretations

- using benign projections and introjections

As always, the choices among behavioral management, supportive psychotherapy and exploratory therapy are ongoing and changing moment-to moment, and in many instances involve combinations that you invent on the spot for working with a particular patient.

37b. The Patient’s Stage of Change

Patients differ in their readiness to change their drinking behavior. A therapist needs to respect the patient’s degree of readiness in order for treatment to be effective. For a discussion of the stages of change, see Section 40.

PRECONTEMPLATION OR DENIAL

A person in this stage sees no problem with his/her drinking, or refuses to focus on the problem.

Part of a therapist’s job is making the person’s drinking a legitimate topic for discussion and understanding. The work can include examining –

- the issues that got him/her into treatment at this time. If the patient doesn’t see drinking as the problem that needs to be dealt with, then he/she must have an idea about what the problem is. While this could allow the person to self-justify, this topic can also segue into issues of drinking, as a response to the “real” issue, a mistaken interpretation on the part of others, a [possibly recurrent] result of unlucky circumstances, and so on. If nothing else, looking at this question provides an opportunity to begin building a treatment alliance.

- why drinking is important to the person – what he/she likes and dislikes about drinking. This can include discussion of the anticipated and actual effects of drinking in a variety of typical circumstances, as well as a review of immediate and long-term consequences.

- the patient’s history with alcohol, including childhood exposure to family drinking. It can be informative to look at how and when the person started drinking: the circumstances, the motives, etc., especially in the context of his/her history and background.

- the advantages and disadvantages of drinking. This can be of some interest to patients with more intellectualized defenses, if it is handled in the abstract and doesn’t challenge the person’s denial. It can also lead to a more personal discussion of the risks of alcohol use and how the patient deals with them. The patient may not have thought about risks seriously, and the discussion could be helpful by bringing those risks into awareness. The patient may also be exposing him/herself and others to risks he/she hasn’t considered, and that can be explored as well.

If the person is coming under protest, you may be able to forge an alliance around the perceived antagonist and your patient’s reactions to the pressures to come for treatment. If the pressure for treatment is unavoidable, you may be able to join him/her around the purpose of making good use of your mandated time together.

If you can’t find a handle to use in working with the person, you may need to work on other psychological issues and bring in alcohol-related problems as they arise in the course of therapy. In the absence of a compelling reason to continue, it is likely that the person will stop coming.

CONTEMPLATION

A person in this stage is considering change and/or making tentative first steps toward change. However he/she is ambivalent and can’t make a commitment to it. A focus on the expected consequences of continuing to drink versus changing can help the person articulate needs and fears. Some of those expectations may be open to experimentation.

You can help the person accept and articulate both sides of his/her ambivalence, generally starting with the positive side. [“What are the advantages / good points – about drinking, for you?”] In any case, both sides are seen as important and worthy of exploration.

If the patient is willing to try out some hypothetical experiments, then psychodynamic work can be used to uncover some of the meanings and conflicts in the patient’s reactions. For example, you might ask whether the person can imagine going to a party without drinking, and if so, explore his/her feelings, expectations about self and others in that context, and likely outcomes. Perhaps the person could go through in fantasy the full sequence of drinking: the first drink, the second, and so on to the next day, the hangover and its impact on his/her mood and activities.

At the same time, you can work on the person’s other psychological issues and continue working on his/her awareness of the impact of drinking on his/her life.

PREPARATION

Here the person is making active preparations and choices toward change but hasn’t actually started.

It can be helpful to examine the changes that the person is considering: what they are, what precedents there may be in the person’s life or family, how he/she feels about each possibility, and so on. If you identify environmental pressures to drink, you can also explore their meanings and history. The patient may be unaware of some conflicts around these pressures, and bringing them to conscious awareness can make it easier to handle them.

If the person actually carries out an experiment relative to drinking then it can be examined in session in many ways. For example, if he/she goes to a party with a plan not to drink, then what happens in the real party? Does he/she drink or not? If not, how is it managed, and what are his/her reactions to self, others and the party? If he/she drinks, what led to breaking his/her resolve? Examination of the patient’s reactions and associations can lead in many directions, including behavior changes [ Section 25 ], such as a new plan for the next party or a need to avoid parties for a while.

The way a person reacts to specific plans is likely to be consistent with his/her general defensive operations [see Section 34 ]. Exploration of defenses may have implications relative to his/her other psychological issues as well.

ACTION

In this stage, the person is aware of the need for change, has identified one or more goals, and is actively working toward them. A therapist’s job can include noting the patient’s reactions to taking action. You can –

- examine the patient’s reactions to each action taken.

- encourage the patient to talk with others about alternative behaviors and their effectiveness in managing drinking.

- discuss the patient’s reactions to overall progress and change.

- discuss the patient’s temptations not to follow through, and to lapse.

- re-evaluate the patient’s goals and his/her reactions to them.

- explore any resistances to change.

- strengthen the defenses that help the patient take action and stay on track.

Early on in treatment, psychodynamic work is secondary to behavioral management, because the most important issue is changing the person’s drinking behavior. However, to the extent that intrapsychic and interpersonal issues increase the patient’s stress level, contribute to his/her urge to drink, or need to be addressed as independent issues, psychodynamic therapy can be an important part of early treatment.

EARLY MAINTENANCE

It is important to continue to monitor the patient’s ongoing relationship with alcohol and watch for triggers to relapse. At the same time you need to help the person in early maintenance move on to other issues.

As time passes, the person’s diagnostic picture may clarify somewhat. Some symptoms may abate as alcohol leaves the person’s system. This can present new directions and issues for psychodynamic work.

LATER MAINTENANCE

As a person moves on, psychodynamic work becomes a more important part of treatment. As indicated in Section 38, the focus and dynamics change, with some issues peculiar to recovering alcoholics. In other ways, over time a recovering alcoholic becomes more and more similar to patients who have never had drinking as a primary issue. Treatment of these patients becomes more and more like treatment of non-alcoholic patients – and more a function of patient issues and therapist technical choices.

37c. Exploring Transferences

Patients begin treatment with expectations that are based on many things – some from prior therapy experiences, the experiences of others, media exposure, past history with other counselors, teachers, parents, police, and so on. Those expectations, loosely called transferences, have an effect on what the patient is able to take from treatment.

Greenson, a classic psychoanalyst, defined transference reactions as the “experiencing of feelings to a person which do not befit that person and which actually apply to another.” [Greenson, 151-152].

Therapists differ widely in their use of patient transferences, from ignoring them to encouraging them by attempting to remain as ambiguous as possible, to seeing them as a product of patient-therapist interaction For the latter point of view, see Wachtel [esp.: pp. 176-184] or Aron [1996, esp: pp 47-52]. Currently, few therapists deny their existence, and differences lie in where we see their sources and how we make use of them. Whether the focus is on the patient’s transferential projections under conditions of therapist ambiguity or exploration of the interconnectedness between patient and therapist depends on treatment goals.

Early in the treatment of alcoholic patients, the goal for psychodynamic work is largely support of the patient’s self-control, with regard to his/her thoughts, emotions, circumstances, and behavior – especially his/her drinking behavior. For that purpose, exploration of subtle transferences – however pervasive they may be – is typically not an effective direction to emphasize.

This is not to say that a patient’s perception of the therapist and the therapy are unimportant at first, but rather that they can become a distraction from the early purpose of the treatment. The opportunity for disruptive transference is minimized and the focus is on reality issues. The therapist is a real person who is providing concrete help.

Transference occurs no matter what and may require the attention of patient and therapist. This is especially of negative transferences, as when the patient sees the therapist as a demanding and hostile authority figure, like a policeman or critical parent. Such a perception could encourage the person to be evasive, avoidant or deceptive. Left unaddressed, it could increase to the point that treatment appeared intolerable and the patient would feel forced to leave.

At the same time, positive transferences to the therapist may be left unchallenged early on, if they contribute to the patient’s early work of staying sober.

As treatment continues and the patient gains control over more aspects of him/herself and his/her life, therapy can and should be directed to more subtle intrapsychic and interpersonal issues, which can include unrealistic positive fantasies about the therapist. While the risk of relapse may always be present – for some patients more than others – treatment of stable alcoholic patients can be much more like the treatment of patients who don’t have alcohol misuse as a central issue.

37d. Working with Denial and Other Defenses:

Ego defenses distort reality in order to serve a purpose, such as the management of emotions, and the preservation of self-esteem, safety and continuity, or the defense of some other aspect of self that the person values and can’t handle directly. Defenses can operate consciously or unconsciously [Blackman, 2004, p.4], but the person is typically unaware that any distortion is taking place.

Like other people, alcoholics use a variety of ego defenses, some of which maintain and justify their addiction. Common defenses include rationalization, denial, projection, minimization and splitting. For many people, drinking is itself part of their defensive structure, a chemical adjunct to the denial and avoidance of issues or emotions they don’t want to face.

Defenses are inherently neither good nor bad, and they need to be evaluated in terms of their function. Some lead to drinking and other undesirable consequences; others help the person function more effectively.

It can be helpful to inventory the person’s defenses and support the ones that make the person stronger and better able to adapt. For example, obsessive defenses can be helpful, if they help a person handle painful emotions or focus on skills that work toward recovery. Introjection can be used in the development of normal psychic structure [Blackman, 2004, p.7].

According to traditional psychoanalytic literature, defenses should be addressed before the unconscious content of the patient’s productions [Greenson, p.137]. However, this rule of thumb may assume a level of structuralization that an alcoholic patient doesn’t have. The assumption appears to be that if an ineffective defense is interpreted, the patient will then resort to more effective ways of operating. As a consequence, the unconscious determiners of the patient’s neurotic behavior can become conscious and be examined. However, an alcoholic patient’s defense is too quickly interpreted, he/she may experience the interpretation as an attack or breach of empathic support. An attack on a defense may also lead to confusion and anxiety that are experienced as intolerable leading the patient to resort to another defense, resume drinking, or leave treatment.

Early in treatment, all of an alcoholic’s defenses should be approached with caution; but some, especially those that interfere with behavioral control, must be addressed. Later on, when the person has established behavioral control over drinking, an attempt may be made to examine unconscious psychological sources of the need to drink, and at that time, it may make sense to try to clear away some other defenses as well.

Maladaptive defenses are generally clarified, confronted, undermined and actively discouraged [see Rockland, 1989]. A therapist can even encourage use of another defense.

For example, if a patient says, “Why does she keep saying I’m too accommodating? I don’t think I am.” A therapist might respond with, “That’s very important. Let’s come back to it later, when you have your drinking under control.” In this case, the therapist’s intention might be to undermine denial and strengthen repression relative to the issue being discussed.

See Section 34 for more on this aspect of treatment.

Typically, modifying defenses and resolving psychological issues are not sufficient to stop drinking, however, because –

- drinking is still a part of the person’s defensive repertoire, that he/she is likely to fall back on when not thinking or when under additional stress.

- drinking over time comes to service many motives and help the person avoid many issues. Even if several of those issues are resolved, a person may still drink to deal with others.

- the behavior of dependent or abusing alcoholics may no longer be sustained primarily by unconscious conflicts, so uncovering them won’t stop the behavior.

Early in sobriety, issues and feelings that had been self-medicated by alcohol may return and present problems for the patient. Forcing a patient to face them too soon or too fully runs the risk of triggering a relapse. At the same time, exploring any one of the patient’s avoided issues in treatment can also lead to better solutions to that issue, reducing the need to be defensive about it, and possibly the need to drink as well. This presents a dilemma with risks on either side. We must proceed with caution, attempting to expose and resolve some underlying issues, while watching and asking about possible increases in anxiety and temptations to drink.

37e. Strengthening Ego Functions

Early in treatment, therapy functions to help the patient gain control of him/herself. In psychoanalytic terms, we are working to support the patient’s ego functioning.

Alcoholics may be deficient in many of the psychic structures needed for adequate self-regulation as well as skills for coping with external reality. These can include

- ability to obtain need satisfaction.

- relationships, “object relations”.

- self care.

- internal comforting.

- self-validation.

- obtaining nurturance and validation from others in a consistent, mature way.

- ability to anticipate danger.

- ability to worry about, anticipate, or consider the consequences of their actions.

- self-regulation of his/her own behavior and emotions.

Kaufman [1996, chapter 6] discusses treatment of a variety of personality disorders in addicted people.

One general approach to dealing with many of these issues is supportive therapy which, according to Rockland [1989, Chapter 5], helps to improve the patient’s ego functioning along a number of dimensions at the same time. A therapist using supportive therapy –

- supports reality testing by “clarifying, confronting and undermining primitive defenses,” such as projection and externalization.”

- strengthens the patient’s regulation and control of drives by “discouraging impulsivity and encouraging delay and sublimations.”

- improves object relations by “encouraging and praising healthier modes of relatedness.”

- works to improve thought processes by “confronting and clarifying vague, overly circumstantial or tangential thinking and idiosyncratic logic.”

- improves the patient’s synthetic function by “confronting, clarifying and undermining excessive splitting operations.”

37f. Exploring Reactions to Life Events and Situations

Everything in the patient’s life has potential for understanding in terms of its impact on his/her moods, self-concept, etc.

Part of treatment involves preparing the patient to handle risky situations and feelings, and it is important to check repeatedly with the patient about his/her temptations and opportunities, ways of coping, etc.

This includes the person’s reactions to all forms of adjunctive care. Exploration can help the person handle mistrust of a prescribing physician, issues that come up in couples therapy or the difficulties in sticking with an exercise program.

A re-framing of a patient’s resistance to a medical referral might open the door to exploring some of the unconscious meanings of his/her reactions:

“I’m not going to a psychiatrist: they just want to drug you up.”

“Have you ever thought of alcohol as a drug?”

It can be very helpful to explore the patient’s reactions to self-help group participation to understand his/her feelings, expand on ideas raised in the group, and handle defenses engaged by participation in the group or the need to participate in it. For example, a patient who objects to the concept of a “higher power” may have had bad experiences with formal religion or have had argumentative atheists as role models. Exploration of these issues could lead to greater tolerance for the language of the group and a better appreciation of the patient’s assumptions and biases. A patient who is critical of other group participants for their style, obsessive repetitiveness or lack of participation may benefit from looking at his/her own style and obsessions in that context. Knack [2009] provides a program for integrating psychotherapy with AA involvement.

Exploring Emotions

A common problem for drug and alcohol misusers is difficulty articulating and distinguishing different emotions. If a person isn’t sure of his/her emotional reaction, specific reactions are more difficult to understand. Many different reactions can run together in the person’s awareness, and the situation can seem overwhelming. This is especially problematic in negative states such as fear, anger, disgust, envy and guilt. This leads to confusion about what to do. When things become overwhelming, the person may have an increased temptation to escape the pressure through drinking.

37g. Exploring Triggers

As indicated in Section 27, it is important to explore in detail the immediate antecedents to the person’s drinking. These can be multiple and complex, and you shouldn’t assume that because you have found some you have found them all. They can include –

- specific moods or emotions [e.g.: excitement, boredom, anger, confusion, anxiety, depression, etc.] and their implications and meanings. A possible question might be “What do you think would happen if you let yourself be angry and didn’t try to tune out by drinking?”

- situations and times [eg: happy hour; walking past a bar on the way home; Friday night when the wife and kids have gone to bed; watching sporting events on television; etc.]

- physical stresses such as chronic pain, fatigue, or difficulty falling asleep.

- associations [eg: flashbacks to traumatic events; realization of personal failure; anticipation of an upcoming event, etc.]

In addition, any of the triggers previously identified is a possible candidate for exploration. Whatever produces an automatic and unconsidered urge to drink constitutes a risk for a lapse or relapse [see Section 33 ]. If the patient can increase awareness of the antecedents, meanings, and emotional impact of triggers, it may be possible to reduce their power. This can, in turn, increase the opportunities for behavioral management. Occasionally, a patient will simply lose all interest in drinking.

Once a patient is alerted to the concept of triggering situations, thoughts and emotions, he/she is more likely to talk about them, even when describing other events of daily life. When triggers are mentioned, you can explore them. When the patient is tempted to drink or has a lapse, you can explore it with regard to its antecedents: conditions or social settings, intrapsychic conflicts, fantasies, ego weaknesses that need support from drinking, etc. These then can be handled with your usual therapeutic approach.

37h. Examining the Consequences of Drinking

Drinking is a relatively passive and indirect solution to many issues that leads to unintended consequences. Becoming more aware of those consequences may enable a person to find more active solutions, solutions that put him/her more in control of his/her life, with fewer unintended consequences.

Exploring consequences can be a way to learn more about a patient’s defenses, as he/she tries to examine what happens as a result of drinking. It also can be motivating to some patients, to look closely at the real consequences of drinking – motivating them to try to find ways to reduce or stop their alcohol use.

IMMEDIATE CONSEQUENCES

How you use this perspective depends on whether a person is actively drinking or not, as well as the person’s stage of change.

For active alcoholics, you can examine the consequences of drinking between sessions: explore the person’s reactions while drinking, the same day that he/she was drinking, or the next one, to look for negative consequences. As each one is identified, it can be examined in detail.

If he/she is a serious drinker, opportunities for mild confrontation will be abundant. For example, “Do you think that your bad mood on Saturday could be related to something that happened on Friday or Friday night?” [Like: being hung over??]

For a person no longer actively drinking, the consequences may already have been forgotten or woven into personal myths about drinking, but there still may be sufficient recall of specific events to work with.

You can examine the consequences of not drinking, too. This can happen naturally with respect to particular situations in which a person is unable to drink. Or he/she could plan not to drink, as an experiment, then look at the consequences. Or the experiment can be conducted hypothetically [“What do you imagine would happen if -“] However, a hypothetical experiment is generally not sufficient, and it would need to be followed-up with data from real events.

Especially watch for increases in any symptom that the person was attempting to manage by drinking, or for unexpected relief from negative consequences. [For example, the comment, “I feel more alert recently.” -is an open door for questions linking the better feeling to having stopped drinking.]

LONG-TERM CONSEQUENCES

Go over the patient’s drinking history. Include when he/she began drinking, and the situations and conditions that he/she typically drinks. If the patient has experienced increasing tolerance (the need for more alcohol to achieve the same psychological effect) or increasing frequency, that can be pointed out as a sign of danger.

Examination of the patient’s family history may offer evidence of an inherited predisposition to alcohol or drug dependency. Ask about parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts and uncles relative to mental disturbances as well as addictions and discuss the possibility that the patient may be more susceptible if relatives have had similar issues.

If a relative or friend attempted to manage his/her life with alcohol, that too can be considered with regard to his/her success or failure at management, unintended consequences, etc. If a relative or acquaintance has or had serious long-term physical consequences of alcohol misuse, these can be explored and possibly used to predict long-term consequences for your patient. For example, if a patient says “My mother didn’t even know I was there when she was drinking,” you may have an opening for questions about your patient’s emotional availability to people s/he cares about when drinking. This in turn may provide some incentive to cut back or stop drinking.

Examining the long-term consequences of not drinking [“How are you managing without drinking?”] may lead to a discussion of long-term gains or losses, unexpected consequences, triggers and temptations, or a need for alternative ways to cope with moods or situations.

AVOIDING RELAPSE

For a patient who is currently sober but tempted to drink, you can try asking him/her to imagine a full-blown relapse in detail – what would trigger it, how it would progress, how other people would react to him/her and what the short- and long-term consequences would be. The patient wouldn’t be in treatment if the consequences are all positive, so this approach is likely to stir up some issues that can be profitably explored.

If the temptation seems likely to lead to a lapse, it might be a time to re-introduce some behavioral controls [ Section 25 ] or techniques from motivational interviewing [ Section 24 ].

37i. Finding Alternatives to Drinking

Drinking may be a way to manage a person’s emotions or reactions. It is important for the patient to work in the present to find better ways of dealing with his/her issues and symptoms without resort to alcohol, and to find more effective ways of handling conflict and stress.

It may be helpful to explore issues such as –

- why drinking works.

- alternative ways of coping and the patient’s reaction to them.

- feelings about abstinence as a goal.

- feelings about trial periods of not drinking.

- reasons previous attempts to stop failed.

37j. Treatment of Other Disorders

It is not unusual for another disorder to become apparent in the course of treatment. An alcoholic patient may also be bipolar, or suffering from a major depression or posttraumatic stress. Generalized anxiety disorder is common among alcoholics; as are a variety of physical issues such as chronic pain or sleep disorder. If the person has another clearly identifiable psychological disorder, you will need to be prepared to make treatment decisions about how to proceed. Options include –

- your own concurrent treatment of the psychological disorder and the drinking problem. If both are essentially psychological issues, your ability to coordinate the two aspects of treatment can be valuable.

- management of the other disorder [possibly through medication] while the patient’s drinking is brought under control; then a gradual switch to work on the other disorder.

- referral to a specialist for the treatment of the other disorder. This option might include regular contact with the specialist to coordinate the two aspects of treatment.

- inpatient treatment for dual diagnosis [Section 29]. This is especially needed when the patient is at risk for self harm or harm to others, or when the two disorders are severe enough that management of his/her daily life is necessary.

37k. Other Common Psychotherapeutic Issues

The full range of usual psychotherapeutic issues is of course open to investigation and treatment, including concerns about the patient’s current family, family of origin, reactions to others, behaviors, etc. However, it is not enough to uncover presumed causes of the patient’s alcoholic behavior in childhood experiences. Some people with a history of childhood abuse, neglect or unhappiness become alcoholics, others don’t. It may be helpful to uncover a connection between such past experiences and current drinking behavior, if that connection can then lead to re-framing of the experiences, re-interpretation of current experience, shifting of defenses, resolution of conflicts, etc.

If the person is aware of other psychological issues that need addressing, you can work on them, while moving at the same time toward greater awareness of the effects of alcohol use on those issues.

If the other condition is clearly independent of drinking or a precipitator of drinking, it may pay to work on it early in treatment. Otherwise, it should probably be postponed until later, when the person has been sober for a while. Often other psychological disturbances are the product of alcohol consumption and abate without explicit treatment after a period of sobriety. In the latter case, working on them is not only a waste of your time, but also discouraging, since they don’t respond to psychotherapy.

It is widely recognized that treating a person’s psychological issues may not be sufficient in itself to stop the person’s drinking. On the other hand, the other psychological issues need treatment also, and if left untreated may pressure the person to return to drinking. Here it is assumed that you already have a repertoire of strategies for handling other psychological issues or will seek them as needed.

CONFLICTS

Common conflicts for alcoholics include

- fear of closeness and dependency

- fear of failure or success

- conflicts about anger and aggression [their own and others’]

EMOTIONAL ISSUES

A person with a history of heavy drinking may also have a history of consequences to deal with. Drinking may have led to behaviors that a sober person realizes are unacceptable. An alcoholic person may justify or ignore the behavior, or possibly even drink more as a way of wiping it out.

Alcoholics may use alcohol for –

- self-regulation of affect (esp.: anxiety or depression).

- tolerance of affectionate or aggressive feelings.

- increased experience of self-esteem.

- release from tensions and inhibitions.

- coping with social pressures, as in parties or meetings

- to go to sleep.

They may be especially vulnerable to –

- guilt, or

- narcissistic injury.

The person may be confronted with a variety of reactions to his or her own prior behaviors. This could include –

- guilt for emotional harm done to others while drinking, through ignoring them, criticizing excessively, belittling, angry confrontations, or excessive dependence and clinginess.

- guilt for having caused harm to others, through physical fights, destruction of property, driving accidents, or other accidents.

- embarrassment and shame for inappropriate behavior, attitudes or appearance.

REAL LIMITATIONS

A person may also have to deal with other limitations, all of which have psychological repercussions and require attention. Physical handicaps, disease, cognitive disorders, legal complications, financial limitations –all can benefit from a better understanding. When an issue results from the person’s prior drinking behavior, the problem is more complicated, and there is greater need for exploration. A person needs to examine his/her reactions as well as plan for future management of the issue.

Psychotherapy can help the person look at these behaviors, understand them, and learn to accept him/herself and his/her history. It can also help the person look at alternative ways of reacting in the future.

37m. Dealing with Lapses and Anticipating Relapse

Every lapse is an opportunity to explore triggers and consequences, if the person continues in treatment, talks about it, and doesn’t fall into relapse [Section 33]. If the person is in full relapse, outpatient therapy – especially psychodynamic psychotherapy – loses much of its power, and behavioral measures may be needed. On the other hand, you may not even know that a patient has relapsed, and therefore be unable to react effectively and in a timely way.

When a lapse doesn’t lead to relapse, it is important to ask what allowed the person to stop. Because some people have a tendency to credit outside forces, it is worth pursuing the internal activity that allowed the person to recognize the risk and work along with whatever outside force he/she first gives credit to, e.g: “What about you allowed you to listen to your brother this time?”

In avoiding relapse, it may be helpful to identify life issues a patient has and work on developing corresponding skills; for example:

- developing prescribed responses to internal changes that could lead to relapse: what does the patient do – and not do, once he/she is aware of symptoms that may predict a relapse?

- developing prescribed reactions in case the person does relapse. Who will find out and how? Where can the person go for help? For example, a person who is in daily contact with his/her AA sponsor not only has the sponsor as a resource. The sponsor typically is attuned to signs of relapse and quick to take action when it occurs.