SECTIONS: 5 | 8 | 16 | 19 | 21 | 22 | 24 | 25 | 39 | 44 | 46 | 47 | 48

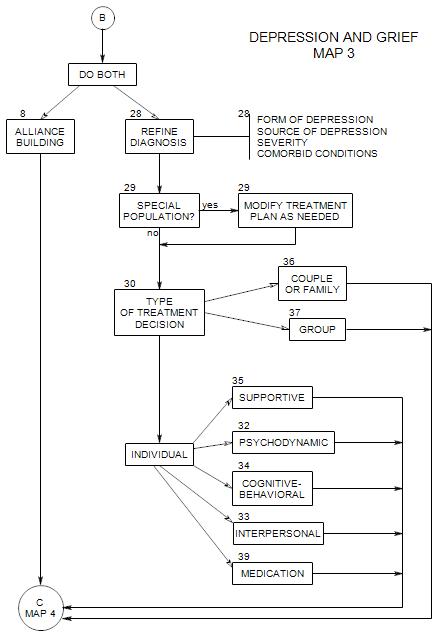

SECTIONS: 8 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 39

-

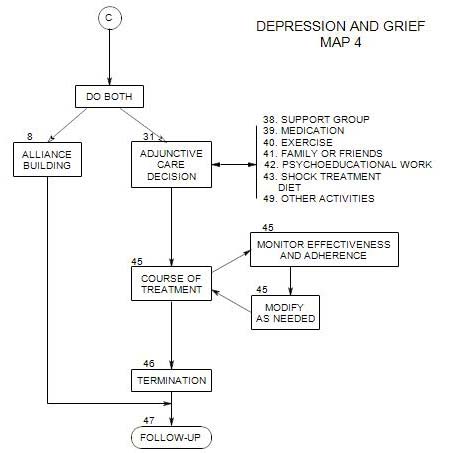

This section coordinates with Section 31 (Adjunctive Care Decision) and Section 45 (Course of Treatment) on Map 4.

In Sections 30, 31, and 45, we are deciding how to treat this patient: choosing a primary form of treatment and any additional services that can be of help, then following the patient through the process of gaining short and long term relief from his/her depression.

The overall treatment process will be governed by

- the form of treatment you consider primary.

- adjunctive treatments.

- case management issues.

- external limitations and pressures [patient’s life, your time limitations, financial constraints, demands of third parties such as managed care reviewers].

This section is divided into several subsections:

- Deciding on the goals for this patient’s treatment

- Patient factors that affect the choice of treatment

- Treatment options

- Making the choice

- Changing your choice for this patient

The process of making choices and carrying out the treatment affects the outcome. Part of the process involves a decision about the extent to which the patient and/or the patient’s family should be involved in selecting and carrying out the treatment.

Chances are that this patient’s depression is the consequence of multiple convergent causes:

- hereditary.

- neurochemical imbalances.

- social conditions and pressures.

- childhood losses.

- recent disappointments and conflicts.

- customary and habitual ways of thinking.

The treatment problem consists in determining what kinds of interventions are likely to be helpful in breaking the logjam that has led to the depression, then carrying out those interventions, and evaluating the results.

The treatment itself consists of ongoing management of the patient [Section 45 ], in which some form of psychotherapy is provided, along with other services.

The psychotherapeutic position is that at least part of the patient’s depression results from some behavioral, cognitive, or emotional problem, and relief from depression follows when the underlying problem is resolved.

30a. Goals of Treatment

Typically, patients only want to feel better, to be less depressed. This is reasonable, but not enough.

Therapeutically, there may be some treatment goals that are common to all forms of psychotherapy. These may include:

- for the patient to gain a sense of control of his/her life, within reasonable limits.

- for the patient to be able to accept support from others.

Among other things, patients must may need to…

- recognize the signs of depression.

- cope with their anger and shame.

- repair family ties, careers, friendships that were disrupted by the patient’s mood fluctuations.

- correct habits of social withdrawal.

- correct overdependence on family.

- cope with temporary setbacks.

30b. Factors Affecting the Choice of Treatment Approach

Your choice(s) will depend on your treatment goals, your own training and preferences, and patient qualities. Some of the latter are discussed below.

PATIENT EXPECTATIONS

Effective treatment must either be consistent with patient needs and expectations, or clearly justify to the patient the use of some other approach. Therapists who begin by “doing what they do” may drive patients from treatment.

A first step is to determine just what the patient expects from you, and you may have to accommodate to that expectation to some extent, at least during the initial stages of treatment.

If the kind of treatment that you can provide or think is best for this patient is different from what he/she expects, you will need to address the discrepancy or risk an early termination. You can

- negotiate a compromise.

- have a trial period.

- refer the patient on to someone else.

BIOLOGICAL VS REACTIVE DEPRESSION

If the depression appears to be largely biologically based, it may be more likely to respond to medical or physical interventions than to psychological ones. A primary treatment for seasonal affective disorder is a light box – a physical intervention. A patient with recurrent major depression may need a base of control with medication and psychotherapy to help manage his/her reaction to the depression and need for medication.

On the other hand, if the patient’s depression appears to have had a beginning and is triggered by interpersonal events, medication may be ineffective, have undesirable side effects, and discourage the patient relative to all treatment.

DEPRESSION IS EPISODIC VS ONGOING AND CHRONIC

When the patient’s depression is episodic, you are more likely to look for circumstances or events that serve as triggers for the episodes. Then you need to know the meanings of those events or circumstances to the person, in order to understand his/her reactions.

To the extent that the person is consciously aware of the meanings of the triggers for his/her depressive episodes, a cognitive approach can be helpful. The more that the meanings of the trigger events are hidden from the patients conscious awareness, the more helpful a psychodynamic approach can be.

The more that the patient’s depression is chronic and longstanding, the more helpful a psychodynamic approach is likely to be, because here again, the origins and meanings are hidden from conscious awareness.

CONTROL ISSUES

A patient’s dependency vs. need for self-control may also have an effect on the type of treatment chosen.

Some very dependent patients may only be able to conceptualize treatment in which the therapist takes over and performs a cure. This might include a wish for advice or sympathy. However, they might also not follow advice and might think they have fooled the therapist, who is too sympathetic. Such a person might best tolerate a beginning using primarily supportive techniques [ Section 35 ], including a further examination of the patient’s goals and expectations.

Other, more controlling patients may try to run the treatment so they can feel in control of themselves and safe with the therapist. Here also, further examination of their needs and expectations in the light of possible therapeutic success should be addressed. Clear limits must be set, and the roles of therapist and patient defined.

LIFE TRANSITIONS

CAPACITY FOR INSIGHT

PHYSICAL, SOCIAL, OR ENVIRONMENTAL LIMITATIONS

PSYCHOLOGICAL MINDEDNESS

Patients who look inward for causes of their own unhappiness may be better candidates for psychodynamic, insight-oriented therapy than patients who blame others, the government, the climate, their spouses, etc. The latter group may benefit from cognitive approaches that examine belief systems carefully and systematically.

STABILITY OF PATIENT’S ENVIRONMENT

CAPACITY FOR FORMING A RELATIONSHIP

STAGE AND SEVERITY OF DEPRESSION

OVERALL LEVEL OF FUNCTIONING

The type of approach that may be effective with a particular patient can depend on the patient’s overall level of functioning. A neurotic patient may be able to tolerate continued depression for a period of time, during which seemingly remote topics are discussed in treatment, with the understanding that the discussion will lead eventually have an effect on the depression. Even at the beginning of treatment, a neurotic patient will be thinking in terms of the underlying causes of his/her depression.

By contrast, a borderline patient who is depressed is likely to be vague about causes but focused on the feeling. The presentation will be chaotic; the reasons, when given, will be vague or inconsistent. A borderline or psychotic patient may only be interested in symptom relief and unable to tolerate a treatment that is not obviously and directly related to that task. A borderline patient may also engage in episodic self-destructive behaviors.

30c. Treatment Approaches

There are many treatment options, each predicated on a particular understanding of the presumed source of the patient’s depression. Here they will be considered separately; however, most therapists use their own combinations of therapeutic techniques, and the relative weights of the component approaches may vary from patient to patient and throughout the course of treatment for a single patient.

A mixed approach might use some supportive techniques as a foundation, then use cognitive-behavioral techniques as a first primary approach. If the depression hadn’t lifted, the therapist could move on to a psychodynamic approach, family or couple therapy, or group techniques.

A primarily COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL APPROACH [ Section 34 ] centers on understanding the functional relationships between thought processes an contents, overt behavior, and mood disturbance. It can be especially helpful to a person who

- is not available for intrapsychic exploration, but whose depression is based on his/her ideas about what he/she should think or feel.

- Is able to identify “triggers” for depressive thoughts or episodes and learn alternative thoughts or actions to take.

A PSYCHODYNAMIC APPROACH [ Section 29 ] might formulate the patient’s problems in terms of

- an internal conflict that is out of the person’s awareness.

- unconscious motives.

- pervasive but subtle feelings or attitudes.

- identifications from early childhood that interfere with effective living.

- early traumas that continue to affect the patient’s views of self and others.

An INTERPERSONAL APPROACH [ Section 33 ] focuses on the relationship between a person’s interpersonal issues in the here-and-now and his or her depressive symptoms.

INDIVIDUAL SUPPORTIVE PSYCHOTHERAPY [ Section 35 ]

Supportive interventions may be helpful [Rockland, 65-6] when the patient—

- is grieving for an identifiable loss, and you need to help him/her get through the grief to see if additional work is needed on the depression.

- is in crisis and needs help getting through it before intrapsychic work can be attempted.

- doesn’t want to go beyond support, doesn’t want to work on intrapsychic issues.

- is simply ignorant and only needs reassurance and encouragement in order to proceed normally and deal with his/her issues.

- is so internally depleted that there is no point to attempting introspective treatment, and all you can do is help him/her keep moving on.

- lacks some ego functions, and you need to provide them temporarily while he/she develops his/her own.

- is faced with life-issues that are likely to limit treatment, such as money or moving.

- doesn’t want to change, or wants to change someone else.

- is under chronic environmental stress.

- is not psychologically-minded.

- acts-out, somatizes, or has difficulty putting feelings into words.

FAMILY THERAPY [ Section 36 ]

This can be helpful…

- when the patient’s depression seems to be a function of role or status in the family.

- when the identified patient seems to be expressing the depression of someone else in the family.

- when the patient is a child or adolescent.

- when the focus is on communication, on trust, or on responsibility to others or by others.

COUPLE THERAPY [ Section 36 ]

- when the patient’s partner seems to be contributing to the patient’s depression.

- when the patient’s depression seems to be a symptom of the relationship rather than the individual.

- when the partner can throw significant light on the patient’s issues.

- when excluding the partner could lead to the partner’s sabotaging the treatment.

- when the partner can be a significant collaboration in the treatment of the patient or the relationship.

GROUP THERAPY [ Section 37 ] OR SELF-HELP GROUP [ Section 38 ]

- when the patient is isolated and needs significant contact with others that he/she is unable to find.

- when the patient needs to gauge the reactions of others to his/her behaviors or ways of being.

- when group pressure can be a significant motivator for change.

- when the patient can tolerate group interactions.

- when the patient has adequate social skills.

Differences in approach also lead to differences in treatment of the depressive symptom. Approaches that equate the patient’s experience of depression with the problem try to eliminate the symptom directly. Approaches that view the patient’s depression as a normal reaction to an unhealthy environment try to help the patient modify or leave that environment. Approaches that see the depression as a sign or consequence of an underlying conflict may leave the symptoms at least partly undisturbed, with the idea that symptom relief will be ineffective in itself, and symptom reduction can be an indicator that the underlying conflict has been resolved.

30d. Making the Choice

It is possible to apply any one of these approaches to all depressed patients. To do so requires some ingenuity, and treatment runs the risk of becoming a procrustean bed that ill-fits some patients and may actually harm them.

Often it pays to be able to draw from a variety of approaches in treating a particular patient: possibly handling mistaken beliefs with cognitive techniques, examining interpersonal relationships, and looking for unconscious motives and identifications from childhood.

Sometimes it makes sense to have a combination of individual treatment with couple, family or group therapy. Issues are identified in group or family work, then explored in greater depth in individual therapy. Or, issues identified in individual therapy are raised with the person’s partner present in a couple session.

Thus the choice may not be so much a choice between approaches as a choice of the balance between approaches or a selection of techniques from different approaches.

30e. Changing your Choice of Approach

You may not be locked-in to a particular treatment approach. During the course of treatment your goals may change, and the most effective form of treatment may also change as a consequence. At that point you may decide to modify the treatment [see Section 45 ].