34. DEALING WITH DENIAL AND OTHER DEFENSES

- This section expands on one aspect of exploratory psychotherapy and coordinates with Section 15 [Individual Psychotherapy] and Section 27 ]Ongoing Psychotherapy] . It also relates to Section 2 [Intake] and Section 42 [Intake Issues].

A patient’s defenses can come into play at various times throughout treatment. The extent to which a person uses defenses and the kinds of defenses uses may be related to many things, including the person’s other psychological issues and stage of change [ Section 47 ]. Defenses may lead a person to misinterpret other people’s behavior or the meaning of the situation, with consequent urge to drink. Proponents of motivational interviewing [ Section 24 ] argue that early use of defenses by alcoholics is often in reaction to critical attitudes from their families, law enforcement people and counselors.

34a. Typical Defenses Used by Alcoholics

While recovering alcoholic patients may use any of the full range of ego defenses, some are more likely and should be watched-for by therapists. These include denial, projection, projective identification, rationalization and splitting. Many other intrapsychic defenses and interpersonal strategies may also be used by alcoholics, but the treatment principles remain the same.

Overuse of a limited range of defenses contributes to the patient’s vulnerability to alcohol dependence or abuse.

A natural therapeutic goal would seem to be to reduce the patient’s dependence on these defenses as soon as possible, and thereby reduce his/her need to supplement inadequate defenses with alcohol [if actively drinking] or the risk of relapse [if not]. However, any attempt to undermine the patient’s defenses may actually increase his/her chances of drinking, by leaving him/her open to feelings and conflicts that s/he is poorly equipped to handle. In fact, drinking may be thought of as a defensive maneuver that operates in lieu of other defenses, to prevent the patient from experiencing those same feelings and conflicts. Undermining other defenses may increase the probability that a patient will drink.

A more effective strategy early in treatment is to support defenses that promote sobriety and continued treatment and undermine defenses that are likely to lead to drinking or withdrawal from treatment. Commonly the psychodynamic strategy is to ignore effective defenses and to examine ineffective ones. Examination includes noting them, naming them, asking about their origins, functions, and so on.

Typically, feelings to be avoided include anxiety, fear, guilt, shame, anger and loneliness.

Denial is commonly thought to be the most pervasive and dangerous defense of alcoholics. Active alcoholics deny that they are dependent on alcohol, deny that they drink too much, deny that there are dangerous consequences of drinking, and so on [see Part 34b following]. Drinking itself may be considered to be a form of denial, in which an unpleasant reality is simply put out of mind, as though it doesn’t exist.

Rationalization is the process of finding reasonable-seeming explanations for unreasonable behavior. An active alcoholic uses rationalization to bolster denial and continue drinking, or to explain away the outrageous things s/he has done while drunk.

Displacement see Keller p 98a. See also McWilliams treatment of defenses

Externalization [mentioned in Section 37 ]

Projection occurs when a person disavows his/her own feelings, thoughts, attitudes, etc., and attributes them to others. Projection, including blaming, can be used to redirect thinking and to justify continued drinking and other harmful behaviors.

Projective identification is used here to refer to the tendency to attribute ones own thoughts and motivations to others, without disowning them as in projection.

Splitting, in which the person divides or splits the world and other people into neat categories – commonly making one category or group “good” and the other “bad”.

Sublimation mentioned in Section 37

34b. Denial

Whenever there is alcohol dependence or abuse, we should be alert to the use of denial as a primary defense.

The term “denial” is used to describe a variety of interpersonal and intrapsychic activities, involving the refusal to admit or even recognize aspects of his/her thinking, feeling, or behavior that are obvious to others. Relative to alcohol use, a person may refuse to admit to him/herself that –

- he/she is drinking more than one or two.

- or more than he/she used to.

- or that it has any impact on his/her life.

- or that there is any serious risk.

A person may also simply refuse to discuss his/her drinking with anyone else, and get angry when pressed to do so. In the psychoanalytic literature, denial and other defenses are seen as unconsciously operating – that is, the person has no conscious awareness of using them. In the behavioral literature, they may be seen as strategic – the person sees things differently from the therapist or has made a decision not to admit to behavior that the therapist appears to be challenging [Morgan, p.204].

34c. General Therapeutic Strategies for Dealing with Defenses

In the therapeutic setting, a patient’s willingness to talk about his/her alcohol use will depend to a great extent on the therapist’s attitude and approach. A judgmental or attacking approach is likely to increase a patient’s defensiveness, whereas a low-key, sympathetic approach may lead the patient to greater willingness to look at his/her own behavior and its consequences. See Section 24 in this regard.

At the most general level, the basic strategy for dealing with defenses is to make the person aware of using them. The assumption is that, because they are ineffective ways of handling situations, the person will have difficulty continuing to use them, once he/she is aware of using them. Then he/she will have to move on to some other way of coping with the issue that the defense was attempting to handle.

A variety of therapeutic interventions can be helpful. They vary according to degree of intensity and cohesiveness, and their relative effectiveness must be judged on an individual basis. We may try:

1. Ongoing therapeutic confrontations of the patient within the regular therapeutic setting.

Confrontations need not be angry or critical, but they do have to get the patient’s attention. They may involve –

- pointing out, or leading the patient to realize, the consequences of drinking for his/her life.

- questioning inconsistencies in the “facts” that the patient has presented.

- challenging the patient’s “facts” with other evidence.

Another tactic is to focus on the consequences of using alcohol:

- What happens first when the person drinks, and how does it progress as he/she continues to drink?

- What is the general effect of the patient’s drinking on his/her family, on his/her job, on other interpersonal relationships?

- Is there any impact on the person’s day-to-day functioning, mood, alertness, motivation, or choices of activities?

- Have there been consequences in terms of job raises, promotions, attendance at work?

Such confrontations typically must occur many times, over an extended period of time, before the denial can be substantially affected and the patient motivated to change behavior.

2. Involving significant persons from the patient’s life in the treatment process. This has the advantage bringing to bear social pressures on the patient, not only to conform, but also to accept the judgments of others as to alcohol misuse and degree of danger. It could take the form of simply involving others in the patient’s treatment process [ Section 21 ], of couple therapy [ Section 17 ] or of family or network therapy [ Section 22 ].

MORE CONFRONTIVE INTERVENTIONS

It may be necessary ultimately to place the patient at a desperate choice point, where continued drinking is more painful than abstinence.

3. You may need to consider a law enforcement intervention, when the patient’s behavior constitutes a clear and present physical danger to self or others. For example, if a patient arrives at your office drunk or on drugs, leaves still under the influence, intending to drive home, you need to prevent that from happening – by insisting that he/she call someone to come for him/her, or take a taxi. Otherwise you might tell him/her that you will be obligated to call the police immediately. Or, if a patient is threatening violence to him/herself or others, you are legally required to warn the intended victim and notify the police.

4. A family/network intervention (see Section 13 above), may be necessary. In this case, a single group meeting is used to pressure the patient to accept immediate hospitalization.

34d. Therapeutic Strategies and Stage of Treatment

Although it is important to identify the patient’s defenses in order to understand how and why s/he operates as s/he does, the handling of defenses should change as sobriety continues and the focus of treatment changes.

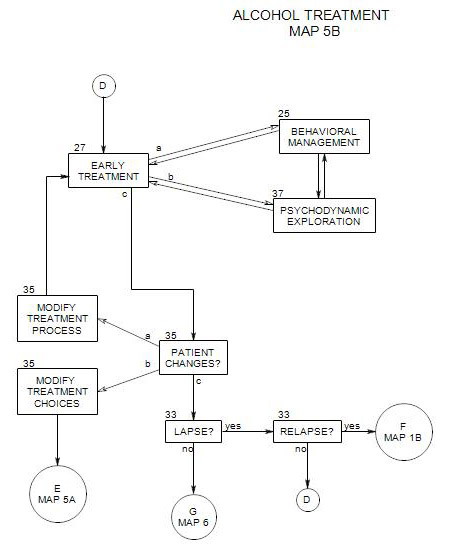

Early on, ego defenses should be respected. They are the patient’s choices of ways to self-protect from unpleasant awarenesses and emotions. If they are confronted before the patient is ready to give them up, a crisis may be precipitated, and the increased stress could precipitate a relapse of drinking or drive the patient from treatment. Because the primary task of early treatment is to maintain sobriety, defenses which serve that goal should be supported and defenses that interfere should be confronted and challenged. At this time, the work is primarily behavioral management, and defenses should be evaluated relative to their usefulness in supporting behavioral tasks and participating in adjunctive care.

A second major goal at this time is to support defenses that operate in the service of adaptation and sobriety.

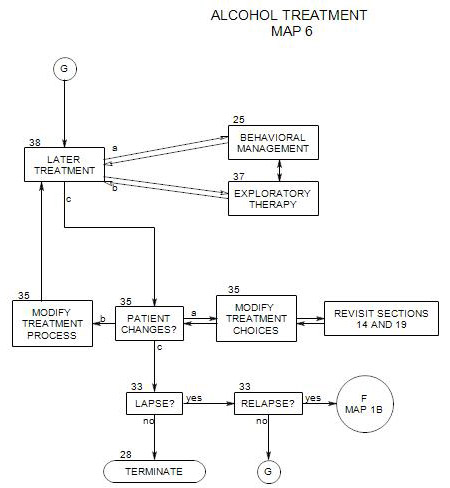

Later on, as the patient’s sobriety becomes more secure, work on the defenses is desirable, to help the patient become more flexible and adaptive. There also may be a change in the patient’s use of defenses as the effects of drinking leave the patient’s system and life style.

How you deal with denial and other defenses depends on many factors, including the patient’s motivation and trust in you, the stage of treatment, the patient’s personality, outside forces, and your own style.

ACTIVE ALCOHOLIC

Active alcoholics are generally considered to be poor candidates for psychotherapy, because their alcoholic defense interferes with the motivation to change. However, with some psychologically dependent or abusing patients, you may decide to treat the person and continue to press for abstinence. Mitigating qualities might include some insight, curiosity about motives, a spouse who is pressing for sobriety, prior therapeutic success, and so on.

In such a case, psychotherapy can be helpful to the patient in understanding his/her reasons for drinking (both historic and immediate), what alcohol does for him/her, and what the short- and long-term consequences of drinking are. Trial periods of sobriety can be attempted, to explore the effect of abstinence or the patient’s ability to remain sober. Alternatives to drinking can be considered and attempted. The immediate stimuli that precipitate drinking can be listed, and the patient’s ability to carry out “controlled drinking” can be assessed.

In this context of exploration, the patient’s defenses can be examined, and alternatives to drinking can be encouraged [including alternative defensive maneuvers]. For some rare individuals, drinking can be controlled. This approach may help him/her manage or control drinking more effectively. However, for most patients, this is an opportunity to encourage him/her to work toward abstinence.

EARLY SOBRIETY

At this point in time, a main focus of therapy is to protect the patient’s sobriety, which is constantly at risk.

A helpful focus at this point is to treat the patient’s drinking as the cause of all of his/her problems. This relieves guilt for past behavior, offers a single remedy, and promises hope for the future. It also finds support from self-help groups.

Specific therapeutic strategies can include many of those used with active alcoholics: reflecting on the causes of the patient’s drinking, the functions it served, etc., as past events. Alternatives to drinking can be examined, including ways of thinking about events and emotions. In this process, the patient’s preferred defenses can be strengthened in the service of continued abstinence. Membership in a self-help group can be discussed and supported as well. Resistance to attending meetings, to working with a sponsor, to taking on responsibilities can be examined and worked on.

The alcoholic’s defenses of choice should not be undermined; rather, they should be directed toward maintaining sobriety. Some examples follow.

Early in sobriety, denial is a valuable asset to maintaining abstinence. The recovering alcoholic tries to put out of mind the thoughts that could lead to drinking: past failures, future temptations losses, guilt, things that could have been. Phrases like “Let it go;” “Try not to think about it;” “One day at a time” use denial in the service of maintaining sobriety.

A therapist may support denial in other ways, by not demanding that the patient acknowledge and reveal all. Too much pressure for self-disclosure may increase the patient’s anxiety to the point of greater defensive reactions, including the possibility of drinking or withdrawal from treatment.

Being sober doesn’t stop a person from using rationalization in a variety of ways: to explain drunken behavior, to avoid anxiety-producing situations, to get special attention (“I need your help, to stay sober.”).

Rationalization can also be useful in maintaining sobriety in many ways – for example: making excuses for not going to places where alcohol is available or for not spending time with heavy drinkers.

Splitting can be useful in helping keep the states of “drinking” and “sober” separate, relegating “drinking” to the past, and offering relief from prior failures. In a related form, all-or-none thinking can be seen in the motto “It’s the first drink that gets you drunk.”

LATER IN SOBRIETY

When the patient has been sober for a period of time – usually a year or more – and his/her sobriety is stable, then treatment can turn to dealing with defenses.

When the patient is ready, denial needs to be replaced by awareness and acceptance – of past failures, of future issues, of the patient’s limitations and weaknesses.

Eventually, rationalizations need to be confronted, so the patient can become more realistic in his/her awareness of self and others, more open and direct about motives and limitations, and more flexible in dealing with the world.

If splitting can be tempered, it can also lead to a less emotionally volatile perspective on others and the world, reduced sense of powerlessness, fewer enemies and oppressors, and a lessened likelihood of relapse.

References

Wallace, John. “Tactical and strategic use of the preferred defense structure of the recovering alcoholic.” National Council on Alcoholism, Inc. ( An ego-psychological approach)

Wallace, John. “Critical Issues in Alcoholism Therapy.” Chapter 3 of