25. BEHAVIORAL MANAGEMENT

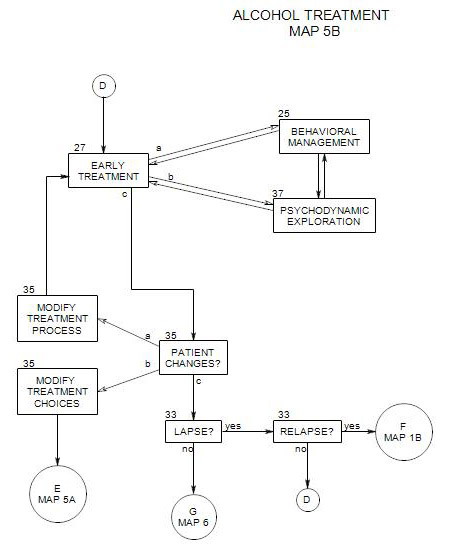

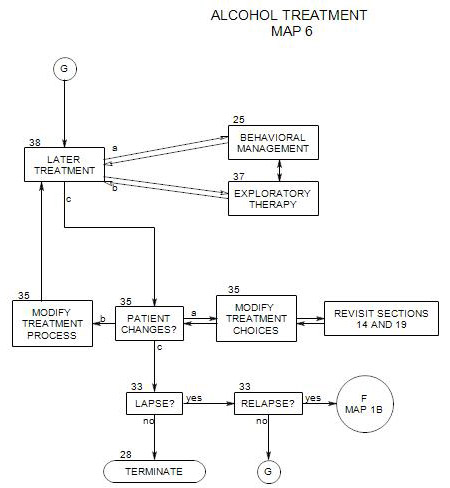

- Behavioral management is one aspect of early treatment, where it is associated with Section 27 and Section 37 [Psychodynamic Therapy]. It is also an aspect of later treatment, where it is associated with Section 38 and Section 37.

Behavioral management is especially important when a person must take action to change some aspect of his/her life. When a patient is actively drinking, behavioral changes are important in moving toward better control or sobriety; when a patient is newly sober, behavioral strategies are crucial to consolidating and maintaining sobriety.

Parts of this Section:

- Managing cravings and triggers

- Dealing with deficits

- Working with people close to the patient

- Patient’s stage of change

- Controlling the situation and opportunities to drink

- Using the results of a behavioral technique as a springboard for psychodynamic exploration

- Recognizing consequences of drinking

- Other potential issues

- Special issues for controlled drinkers

25a. Managing cravings and triggers

Once triggers for drinking have been identified [ Section 27 ], the patient needs to develop techniques to avoid them or neutralize them. Cravings can be seen as cognitive-emotional reactions that have been conditioned and are controlled by reinforcement contingencies. Behavioral therapy involves taking action to undo connections among the stimulus, response and reinforcement.

Managing a craving depends on the person’s strengths and needs to be planned with the patient. It can include –

- distracting oneself, as for example by changing focus from the internal experience of the craving [including emotions and obsessive thoughts] to something external [which could include immediate events or activities.]

- avoiding or leaving a situation where the craving is experienced [by not driving or walking past bars or liquor stores, by avoiding parties where alcohol will be served, or by removing all alcohol from the home].

- working on techniques to endure cravings, such as reminding oneself that they will soon pass.

- carrying a note-card that reminds oneself of the negative consequences of drinking or the benefits of not drinking, and referring to it when tempted to drink.

- dealing with other people to create a network of support for abstinence [or self control]. This might include trying to convince family members to drink elsewhere, avoiding friends who encourage him/her to drink, or asking friends for help with not drinking. New friendships can be started with people who don’t drink – although this takes time. AA is one good place to meet people who make a point of being abstinent.

- arranging circumstances to support abstinence, as by spending time engaging in hobbies and other activities that are inconsistent with drinking.

- general ways of reacting, such as practicing ways of saying “no” and imagining the reactions of others or having the therapist role-play them.

- developing situation-specific reactions e.g.: when eating at a restaurant, ordering before others and choosing non-alcoholic beverages].

25b. Dealing with Deficits

A person’s sobriety can be threatened in many ways. Often people drink in order to manage internal and external situations where they lack more effective skills and reactions. Any skill deficit can lead to an urge to drink. It commonly starts with an emotional or cognitive reaction, such as frustration, anger, lowered self-esteem, or a wish to avoid the threatening situation. The patient’s reactions can then lead to solitary drinking, drinking with bravado, party drinking, or drinking with less discriminating companions.

One way of helping a person cope more effectively without drinking may be to identify the person’s limitations and teach compensatory skills. By doing so you can help to undermine the need to drink.

To do this, the first step is to explore the situations and thoughts that lead to the urge to drink, in enough detail that a clear understanding is developed. If you identify limitations that appear to be leading to the urge to drink, behavioral or educational work may be helpful in dealing with them. Once that is done the work can be evaluated relative both to the deficit and to the person’s alcohol use. It may be enough. If not, further exploratory work can be used to determine what else may be needed.

The table below serves as a map relating some common symptoms to brief descriptions of educational and behavioral treatments that follow. Each of the proposed treatments has been suggested by therapists as a way to reduce patients’ urge to drink by increasing their coping abilities. Because they were developed in separate programs, these treatments may overlap. Also, for any patient, the effectiveness of a treatment depends on the person’s specific needs and expectations, and a program may need to be adapted to fit.

General tension or anxiety

Systematic relaxation

Stress management

Relaxation training

Assertiveness training

Anger management

Dealing with defenses [Section 34] Cognitive therapy

Communication skills training

When a person has difficulty expressing him/herself appropriately, it can affect the reactions of others and the person’s own sense of efficacy and belonging, and be a source of low self esteem. Self expression includes include giving criticism, handling criticism, making requests, dealing with requests from others, and giving and receiving compliments.

Common issues include –

- being too passive and inhibited. This person may feel taken advantage of, unappreciated, weak and bitter. The bitterness can be turned inward to self-destructive solutions, including drinking, or outward, in verbal or physical outbursts.

- being indirect. Others may not understand what the person is trying to say, leading to a sense of frustration or of being abused.

- being too aggressive with others and standing up for him/herself at their expense. Alcohol may be used to bolster resolve or to deal with rejection by others.

Assertiveness involves expressing one’s own needs, wants, and opinions openly, clearly, directly and honestly, while at the same time paying attention to both one’s own rights and the rights of others. Examples of passive, aggressive and assertive behaviors can be found in a table in Epstein and McCrady, 2009[b], p. 113. The goal of assertiveness training is to help people be more direct and appropriate in expressing their thoughts and feelings, especially in alcohol-specific situations, or situations where the inability to get one’s point across can lead to loss of self-esteem and an urge to disappear.

Jarvis etal [2005: pp. 107-119] provide an outline of assertiveness interventions that can be incorporated into a treatment context, together with references to more extensive treatments.

COMMUNICATION SKILLS TRAINING

A person may be tempted to drink in social situations or the anticipation of social situations if talking with others is experienced as unrewarding or painful. Communication skills training attempts to help the patient overcome issues of verbal interaction, and thus feel more comfortable, interact more effectively, enjoy those situations more, and reduce the pressure to drink.

Goals include –

- being able to initiate and continue conversations comfortably.

- being sensitive to social cues from others about their reactions to the patient.

- being able to express important feelings to others.

- understanding the feelings of others.

- taking responsibility for one’s own feelings and opinions.

- expressing oneself positively in terms of requests rather than demands.

- initiating and maintaining conversations.

- expressing opinions in a variety of ways, depending on the situation.

The general protocol includes specific strategies for –

- dealing with silences.

- communicating nonverbally.

- listening actively to others.

- validating others.

- identifying and matching the level of seriousness in others’ conversations.

Exploratory work can be helpful in conjunction with the training, in understanding the internal forces that make communicating so difficult. This can include –

- ways others in the patient’s family expressed themselves.

- messages the patient got from others growing up and their effect on self esteem and willingness to be open.

- the patient’s own self-talk and how it can interfere with communication.

More on this topic can be found in Jarvis etal, 2005, pp. 121-127 and in Monti etal, 2002, pp. 50-64.

ANGER MANAGEMENT

Anger is a natural reaction to frustration, feeling abused or neglected, or becoming aware of wrongful or unfair actions by others. The problem is not that a person gets angry, but that it may be inappropriate, debilitating, or lead to dangerous, unwanted or unproductive behaviors.

Anger is a by-product of a person’s thinking and actions. Anger management deals with [1] ways to deal with issues so that the person doesn’t need to get angry; [2] ways to recognize anger so that it doesn’t lead unconsciously to action that will later be regretted; or [3] ways to manage reactions to anger to make them more effective and appropriate. Techniques include –

- alternative interpretations of situations or another person’s intentions.

- being more assertive.

- appreciating one’s own impact on the situation or other person.

- increasing empathic awareness and understanding of others.

- reducing one’s own tension through stress reduction techniques.

- re-interpreting triggering events or thoughts that lead to anger reactions.

- seeking sources of agreement with adversaries.

- managing the connection between experiencing anger and acting on it.

For more on anger management, see Monti etal, pp. 104-108 and 123-125.

SOCIAL SKILLS TRAINING

Drinking may be a habitual way of coping with the stress of interpersonal situations. If so, training in social skills could be helpful. Patients can be given coaching and practice in dealing with social pressure, interpersonal conflict, the need to please others, and help in enhancing interactions with others [see Morgan, p.216].

Patients can be taught ways to identify situations that could lead to stress and skills specific to their social issues.

DRUG REFUSAL

Refusing offers is a common problem in social living [Jarvis etal, pp. 103-106]. In this approach, you patient is taught ways to refuse offers of alcohol with confidence. It is used with patients who lack confidence in their ability to resist social pressures to drink. Patients are trained in the use of body language and tone of voice, and given specific suggestions about what to say. Often role playing is used to make the training more realistic.

Drug and alcohol refusal is usually thought to be a part of assertiveness training [Monti etal, pp. 215] Specific strategies include –

- clear and firm refusal

- asking others to stop pressing the patient to drink;

- suggesting an alternate activity inconsistent with drinking;

- changing the topic;

- nonverbal communication of seriousness, through eye contact, gestures, facial expressions and voice quality.

Pressures to drink can range from a casual offer to serious insistence. Patients can be taught that their strength of refusal needs to match the pressure they are feeling from others.

More detailed suggestions can be found in Jarvis, etal, p. 103f, Monti, pp. 65-66, and Morgan pp. 215-16

PROBLEM SOLVING

This teaches general skills to work on life problems that could threaten the patient’s abstinence. As proposed by D’Zurilla [1988], problem solving therapy is a general treatment approach that trains patients to re-organize their thinking process and actions and affects their overall way of living. Therapeutic work includes recognition of the pervasiveness of opportunities for problem solving and exploration of maladaptive coping styles.

Others [Monti etal, 2002, pp. 99-102 and Jarvis etal, 2005, pp. 95-99] approach it as one set of skills among many that can be offered to patients, possibly in a single session. If it is offered as one skill among many, it may come up repeatedly and can be returned-to as needed.

As with other educational approaches, the therapist teaches the skills then offers practice in applying them.

There are several steps to problem solving using this approach: [1] recognize that a problem exists and define it [2] generate a variety of solutions [3] select the best solution [4] take action to implement the solution [5] evaluate the effectiveness of the solution. [Jarvis etal, 2005, pp. 95-99]

COGNITIVE THERAPY

A patient’s frustration, depression or anxiety may be in part a consequence of convincing but illogical thinking. If a therapist can identify the errors and convince the patient to think otherwise, some of the impetus for drinking may be reduced, and the patient may function more effectively in other areas of living as well.

Treatment goals include [1] to recognize negative thinking that could lead to drinking and interrupt the negative train of thought, and [2] to challenge common thinking errors and teach more productive ones.

A number of common cognitive distortions have been discussed in the literature. One list can be found in Dryden and Ellis [ p.222]. It includes such thinking errors as –

- all-or-none thinking.

- jumping to conclusions.

- minimizing one’s own accomplishments.

- perfectionism.

Other lists appear in Leahy [ p. 32] and Jarvis etal, pp. 137-8. Each of these resources also includes suggestions for challenging thinking errors and providing alternatives. [see esp: Leahy, 292-305]

Many of these thinking errors are similar to defensive distortions discussed [from a different theoretical and therapeutic perspective] in the ego psychology literature [see Section 34; Blackman, 2004].

Once errors are recognized, the patient is commonly asked to keep a record of using them while simultaneously working on alternate thinking that is more productive.

There are many valuable resources on cognitive therapy, including –

- ¾Heather and Stockwell, Ch 5, 69-86

- Jarvis, etal, pp. 129-143].

- Dryden and Ellis, [esp: list, p. 222]

- DeRubeis and Beck, 1988 [esp: list, p. 276]

RELAXATION TRAINING

If a person drinks to relieve stress or anxiety, then it can be helpful to provide him/her with another way to relax. This is the purpose of relaxation training.

The therapist helps the patient recognize his/her tensions and release them in session. Once the techniques have been learned they can be used to self-calm in everyday stressful situations. [Jarvis, etal., ch 11; pp. 143-153]

The best known procedure is probably progressive relaxation [also known as systematic relaxation and as one form of hypnotic induction]. Here, the person is taught to recognize muscle tension and gain control over it. People code their tension into their muscles, and when their muscles relax, their tension is reduced.

Progressive relaxation involves focusing on one set of muscles at a time [e.g.: left foot; right arm; face], and first tensing those muscles, then relaxing them. Different muscle groups are taken in turn, commonly working from the feet upward. Examples of the procedure can be found in Jarvis, etal, 2005, ch 11; Lehrer and Carr, 1997, 83-116, and in some protocols for hypnotic induction.

Many other forms of relaxation training are available, including –

- isometric relaxation, where the controlled tension comes from pitting one set of muscles against another, without movement [see Jarvis, etal, 2005: pp. 150-151].

- breath control, in which the person is encouraged to breathe slowly through his/her nose as a way to focus attention and gain self control.

- meditation.

- meditative relaxation [see Jarvis, etal, 2005: 149-150] combining deep breathing with a focus on a single word or image.

- guided imagery, in which a patient is led through a series of visual images that encourage relaxation. This is commonly used as a second phase of hypnotic induction, and protocols can be found in works on hypnosis.

- biofeedback, in which skin electrodes are used to help the person become aware of muscle tension and learn to reduce it by controlling feedback from the electrodes.

25c. People Close to the Patient

When you work with families and significant others, they can help you monitor the patient, to watch for changes that might indicate a potential for relapse. They can provide additional information about events in the patient’s life and his/her reactions to them. See Section 21 [Involving Others] for more on this.

Adjunctive care providers can be helpful sources of information about the patient as well.

25d. The Patient’s Stage of Change

The effectiveness of any interaction depends on what the person can respond to. Treatments that are consistent with the person’s stage of change are more likely to have an impact than treatments designed for a person who is either more or less ready to change [See Section 40 ]. The following is organized around those stages of change.

PRECONTEMPLATION OR DENIAL

Here, the person sees no problem, or refuses to focus on alcohol as a problem.

You can try to educate the person about alcohol misuse, but too much pressure could activate his/her defenses. Behavioral management generally requires cooperation between the patient and therapist toward control of one or more agreed-upon issues. It is difficult to come up with behavioral treatments for someone who sees no problem in the behavior being treated. This is a good time for the techniques and approach of motivational interviewing [ Section 24 ].

You may get the person to keep track of the amounts s/he drinks on a day-by-day basis, to look for patterns. But even this minimal action may be perceived as pointless and ignored. However, that and any other action or failure to act by the patient can provide material for discussion either within a management context [“How can we set up this task so you can carry it out?”] or a psychodynamic approach [“Did this task have some special meaning to you?”]

CONTEMPLATION

As with a person in the precontemplation stage, a person in contemplation is not likely to be open to changing his/her behavior – but he/she might be willing to think about change.

Here there is an opportunity to support and expand on the positive side of the person’s ambivalence, without pressuring for actual change. One possibility is to suggest that he/she try one or more hypothetical experiments and imagine how they might turn out. The experiments can be tailored to the person’s opportunities, strengths, and other psychological issues, for example:

- “Could you imagine going to the party without drinking?” and if so, then “How would you do it?” and “Do you think that you could keep from drinking all night?”

- “What do you think would change if you didn’t have the first drink until after lunch?”

- “Do you think that things would be different with your family over the weekend if you didn’t get drunk on Friday night? What could you do? Can you imagine everyone’s reactions?”

- “What do you think would happen if you went without drinking for a month?”

While a person might not actually carry out any of these experiments, thinking about them may ease the way to the preparation stage, in which some small changes are attempted.

If the person will experiment with drinking in different ways, or different quantities, then the anticipated and actual consequences of the experiments can be open for further exploration.

PREPARATION

Here the person is making active preparations and choices toward change but actual changes in behavior are tentative and often ineffective.

You can join the person in this stage by suggesting some minimal experients, while leaving the choices to him/her. The hypothetical experiments of the contemplation stage can be made more concrete and practical, for example:

- “Can you go to the party without drinking?” If the patient says “yes”, then “What can you do to make it easier not to drink?”

- “Could you try to postpone the first drink until after lunch?”

- “Do you think that things would be different with your family over the weekend if you didn’t get drunk on Friday night? What would you do? Could you try it as an experiment?”

- “It would be really helpful if you could totally abstain for a month, so we can see what the consequences are and compare them to your expectations.”

In each case, a follow-up can help identify the components of a successful experiment or the things that got in the way -sometimes, both. Follow-up can also be a time for psychodynamic work [ Section 37 ] on the person’s reactions to an experiment or the issues that arose during the process of experimenting.

ACTION

In this stage, the person is aware of the need for change, has identified one or more goals, and is actively working toward them. A therapist’s job can include helping the patient work toward achieving his/her goals, to evaluate the effectiveness of the actions taken, to help modify actions, to help stabilize the patient in new habits and attitudes, and to avoid relapse.

Behavioral management techniques can include –

- breaking down overall change into manageable behavioral components.

- making plans for specific actions and the order in which to carry them out.

- tracking actual changes, both positive and negative.

- encouraging the patient to report any temptations, cravings or lapses, and using the reports as a basis for formulating more manageable steps.

- keeping track of trigger situations, places and events, and working on strategies to avoid them or manage the patient’s behavior when in those situations.

- keeping track of positive situations or activities – especially those that are incompatible with drinking.

For each planned change, it can be helpful to list its pro’s and con’s, as well as its relation to other changes and the patient’s overall goals. You can also list possible problems and how they can be dealt with.

If other people are needed to help with change, make plans for including them, and enlisting their support and cooperation. If the patient has moved into this stage while in treatment, then this might be a good time to re-visit the adjunctive care choices that were made earlier [ Section 19 ].

MAINTENANCE

The overall plan for the maintenance stage is to continue indefinitely along the patient’s chosen path relative to drinking, consolidate gains from previous stages, and avoid relapse. However, life is continually changing, bringing up new issues and reviving old ones.

This raises issues of consistency in the face of temptation and threat, the security of the patient’s goals, and the effectiveness of the methods chosen to meet them. A therapist can help by continuing to review the goals and methods, and by suggesting revisions as needed.

You and the patient also need to continue to watch for triggers to relapse. A psychodynamic approach can be especially useful here, in identifying internal issues that serve as triggers. Once identified, those issues can often be managed behaviorally.

At the same time, a patient can be encouraged to make life style changes such as –

- developing new relationships, with people who don’t drink.

- enlisting the help of friends in sticking to the patient’s goal.

- pursuing activities that are inconsistent with drinking.

- continuing to participate in self-help groups.

- beginning or expanding an exercise program.

25e. Using Results of a Behavioral Technique as Input to Psychodynamic Exploration

Patients have reactions to every technique, whether the technique is successful or not. Those reactions can be explored psychodynamically, with unpredictable – and thus interesting – consequences. Basic questions like “How did you manage not to drink for the whole night?” can reveal supplementary behavioral techniques that the patient used that time and can use again.

They can also lead to patient associations to other similar situations, prior successes and failures, model adults from the patient’s childhood, and so on. Similarly, when the patient fails, exploration of his/her thoughts can lead to a better understanding of defenses, object relations and so on. That new understanding can then lead to more effective behavioral control.

25f. Making Use of Psychodynamic Findings

25g. Some Other Potential Issues

Lack of compliance with a mandated treatment plan. If a patient has been mandated for treatment and fails to appear for scheduled sessions or is unreachable when you need to reach him/her, you may need to call the probation office and exert pressure either to ensure compliance or to trigger whatever consequence is required.

25h. Special Issues for Controlled Drinkers

A controlled drinker can either be a person whose goal is to drink temperately, or a person – possibly in contemplation [ Section 40 ] – who is in the process of deciding whether he/she is capable of exercising any control over alcohol or should forget about pursuing an impossible goal and continue to drink.

While working on a plan, you can help the person include a variety of techniques for controlling alcohol consumption. These include –

- specific limits on places or times s/he will drink [e.g.: “not in nightclubs or bars; never before bed; never two consecutive days; never before 5:00 PM”].

- specific rules about attempts at mood control [e.g.: Not if you are anxious or depressed].

- listing specific people or organizations that he/she won’t drink with, because the pressure to drink more will be too great.

- keeping a clear record of the amount consumed – by the day if small amounts, by the hour if drinking more heavily.

- spacing out drinks and drinking slowly.

- diluting alcohol with other beverages.

- alternating alcohol drinking with other beverages, such as diet soda or seltzer water.

A well-researched, educationally-oriented approach to consider is Behavioral Self-Control Training [BSCT], which has goals ranging from moderate drinking to abstinence. As described in some detail by Hester [2003], it involves eight steps, that emphasize self-efficacy and self-control.

- agreeing to limits on the patient’s number of standard “drinks” per day and the maximum acceptable blood alcohol concentration.

- patient self-monitoring of drinking.

- changing the rate of drinking.

- practicing assertiveness in refusing drinks.

- setting up a reward system for success in achieving goals.

- learning which antecedents lead to excessive drinking and which don’t.

- learning alternative coping skills to drinking.

- learning ways to avoid relapse into heavy drinking.

Hester also reviews studies of the effectiveness of BSCT and cites a treatment protocol from Miller and Munoz [2005]. Another review of BSCT can be found in Morgan [ pp. 213-215]. In general, this approach may be more effective with problem drinkers who have not been either alcohol dependent or abusive [Morgan, p.207].

Additional readings

For another treatment of this topic, See Washton and Zweben, pp 76-79 and 170-179.