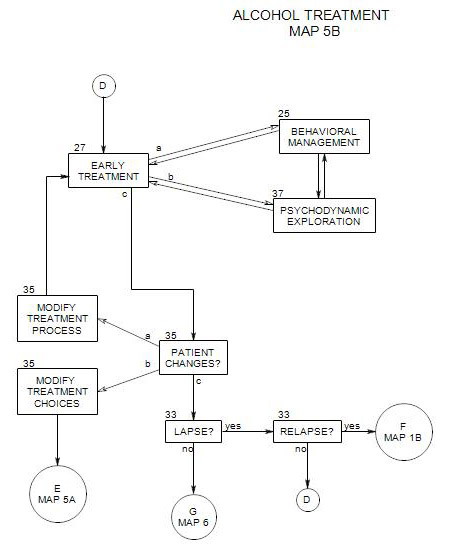

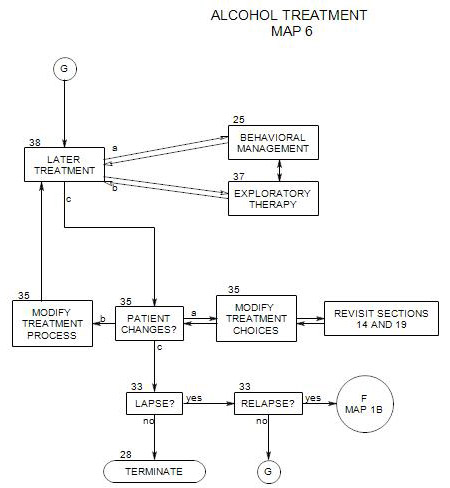

38. LATER ONGOING TREATMENT

- This section follows Map 5 and organizes Map 6. It covers the major time in treatment with alcoholic patients. It coordinates with Section 25 (Behavioral Management) and Section 37 (Psychodynamic Therapy), and Section 35 (Patient Changes).

When a patient has continued actively in therapy and maintained his/her sobriety for a period of time, the situation gradually changes. He/she gains in stability, develops strategies for dealing with temptations to drink, and is able to work differently on his/her psychological issues.

The tasks and temptations change. Behavioral management is still important, but because of increases in internal strength, there is less need for external control. There is also greater opportunity to work on intrapsychic aspects of the patient’s drinking and other psychological issues.

Changes come slowly, and not all changes happen at the same time or at the same pace. A change in any aspect of a patient’s life can have an impact on the overall treatment process and the rest of the patient’s life. Therapy can focus on the impact of each change on the person’s mood, self esteem, relationships and commitment to sobriety.

Ideally, the patient will achieve a long-term sustainable state in which his/her alcohol use is not dangerous or seriously disruptive to self or others, and in which other intrapsychic and interpersonal issues can be effectively treated.

There are many components to treatment, including –

- coordinating alcohol treatment with psychotherapy for other issues.

- coordinating with others, including family members and professionals who are providing adjunctive care.

- balancing behavioral management with psychodynamic exploration.

- dealing with comorbid disorders

This section is divided into several parts:

- Behavioral management vs. psychodynamic exploration.

- Patient stage of change.

- Cognitive issues

- Therapeutic Issues.

- Risks of relapse

- Changes in adjunctive care.

38a. Behavioral Management Versus Psychodynamic Exploration

At any time, an exclusive focus on the person’s alcohol use can leave unresolved other psychological issues that require attention and may provide continuing pressure to relapse. In addition, a patient who wants to focus on other important issues may feel misunderstood by a therapist who insists on an exclusive alcohol focus.

As time passes and patient and therapist grow more confident in the patient’s ability to remain sober, the amount of attention needed to focus on the mechanics of abstinence can be reduced. This means less reliance on behavioral procedures for controlling the urge or opportunity to drink. Behavioral control issues are not gone completely; they may still be important part of treatment, especially at times when the person’s sobriety is threatened. However, they can become generally more automatic and regular. They work, and the patient will continue to use them; but they are less central.

This can be a time when skill building leads to greater benefits, when the patient is better able to take interpersonal risks and develop new skills more effectively. When there are doubts or setbacks, they can be processed therapeutically, with less reliance on drinking to manage discomfort.

Over time, treatment can shift to a more uncovering and expressive mode, to understand the person’s motivation to drink and any other issues that are now more obvious than before. If alcohol had been used to cope with cognitive, emotional or interpersonal issues, they can now be explored in greater depth, with reduced concern that the person will revert to drinking to cope with them.

This can mean a change in the way the therapist functions in the treatment setting, becoming less immediately helpful, less controlling, less available at odd hours, and so on, and encouraging the patient to rely more on self and outside relationships for comfort, ideas about daily life, and practical solutions to problems. Therapy can focus more on uncovering hidden conflicts, increasing self-awareness, and encouraging emotional expression.

If a patient believes that it will be sufficient to focus on his/her other psychological issues, treatment can follow that path; but you should remain skeptical, and alcohol-related questions may continue to be relevant for a long time. Drinking services a variety of needs, and the job isn’t complete after one or a limited number of underlying issues have been identified and examined.

38b. Patient Stage of Change

By definition, a person in later ongoing treatment is in the maintenance stage. Action to stop drinking or continue with a highly restricted level of drinking has been taken and consolidated, and the person has been relatively stable for an extended period of time. However, a person in maintenance still needs to pay attention to drinking issues and temptations and continues to be at some risk for relapse.

One can ask whether a person ever leaves the maintenance stage. It’s an important question, because many people want to put their drinking behind them and move on without thinking about it any more. However, the answer is complicated. First, if the person has a genetic predisposition to alcohol excess, then it’s better to assume that maintenance will never end. At any time, drinking even small amounts, especially in the context of social pressure or stress, could precipitate a relapse. At present, there is no genetic test. For some people, there may be evidence for a genetic predisposition, if there is a family history of drug or alcohol abuse, but an absence of it is not definitive.

Second, if a person has ever been physiologically dependent on alcohol, the risk of relapse should be taken seriously forever. If he/she has been physiologically dependent for a long time or repeatedly, the risk is even greater.

It should be noted that some people move on to abstinence or controlled drinking without further treatment. Klingemann cites a number of studies that report large proportions of patients recovering without professional help. However, as always, the immediate question is about the applicability of those data to this particular patient.

A couple of statistical rules of thumb have been offered. Connors, Donovan and Diclemente argue that a person can be finished with maintenance when he/she is 100% confident of never using again and has no temptation whatever to drink. That’s a tough standard, and risky because it is not capable of objective measurement. As an alternative standard, we might consider the stage ended when the person’s risk of misuse is no greater than that for matching people who have never been dependent or abusive. This is also difficult to measure for one person.

In general, the safest answer is that a person who has misused alcohol should consider him/herself to be in maintenance forever, and continue with some level of vigilance regarding risk of relapse.

38c. Cognitive Issues

In the present organization, cognitive treatments have been parceled out among aspects of behavioral training, exploratory therapy, and – mostly – adjunctive care. However, in a middle phase of treatment, these approaches can be crucial for many patients. It is a time when a patient can become more rational as well as more expressive, can learn new ways of looking at the world. If a therapist is cognitively trained, that approach can be the most effective way to pursue.

38d. Therapeutic Issues

As the patient’s recovery stabilizes and the work becomes more psychodynamic, the issues may change. Exploratory work at this point is less about supporting behavioral control and more about re-evaluating the patient’s interpretations of self, others and circumstances, and uncovering the patient’s unconscious motives and conflicts. Increased self understanding and self awareness leads to different ways to manage impulses and more effective defenses, while also improving general awareness and richness of experience. [For other approaches to these issues, see Kaufman, 1994, ch. 7 and Washton and Zweben, 2006, ch. 11, and Section 37.]

Many different alcohol-related issues can be approached psychodynamically. Below are some that may be especially helpful to pursue. At the same time, other psychological issues can also be explored, even if they don’t appear to be alcohol-related.. Because the patient is relatively stable, there can be less concern that work on them will interfere with a primary focus on drinking.

However, some patients are unstable for a long time after they have become sober. For them, exploration must be done cautiously to avoid triggering a relapse. If the patient’s moods, affects or impulses appear to be dangerously strong, it may be necessary to cut back on exploration, change the topic more frequently, re-focus on behavioral management, or arrange for a medication consultation.

HOW THE PATIENT STARTED DRINKING

If details of early drinking experiences and the reasons the patient first started drinking haven’t already been discussed, this might be a good time to do so. This study has many possible benefits, including –

- patient appreciation of the kinds of pressures he/she was facing at that time and why they led to drinking.

- opportunity for the patient to examine any drinking-related guilt and to forgive him/herself for early mistakes.

- patient awareness of early pressures and the dangers they present, in case they might recur in some form.

- opportunities to expand the treatment focus to other psychological issues, possibly when discussion of early pressures brings up subjects that have been avoided by continued drinking.

MEANINGS OF DRINKING

The meanings of alcohol often occur in the form of associations to drinking or to being around people who drink, and could include –

- meanings attached to drinking based on early experiences, such as trying alcohol the first time, or becoming an adult and being able to drink legally for the first time.

- recollections of drinking in the person’s childhood family, at holidays or parties or in daily life.

- identification with an adolescent group whose members supported each other, possibly through drinking and rebellious activities.

- attending work-related parties, in which co-workers relaxed and supported one another.

- identification with special people – relatives, friends, or lovers, whose drinking may have partly defined them [e.g.:”I was very special to my Uncle Bill. He was always drunk, and everyone else was scornful of him, but I loved him.”]

- the place of drinking in the person’s fantasies.

- opportunities to be “wild and crazy”, or to act out against others, institutions or the law.

- relief from tension or pain.

Exploring these meanings can help the person find their place in his/her history without having to re-enact them in the present. It can lead to re-interpretation of the past and possibly de-idealization of critical people and events. It can also lead to a better understanding of other psychological issues and disorders.

THE FUNCTION THAT DRINKING SERVED FOR THE PERSON

It can help to continue reviewing the ongoing function that drinking had for the person, possibly including the management of emotions or avoidance of conflicts. Some examination of the functions drinking served may already have been part of early work, as the patient dealt with behavioral issues. If so, that examination can be reviewed, continued and expanded. A review can include re-evaluation of the effectiveness of drinking [whether it worked], the underlying issues that made drinking important, and alternative ways to understand and manage those underlying issues.

REACTIONS TO CHANGES IN LIFE

A patient may already have made life changes, or may need to make changes in many aspects of living, or may have to react to changes that have been forced from the outside. There is a complex interaction between a person’s living situation, sense of self, history, and unconscious interpretation of self and experiences, all of which can be profitably examined. These changes can include –

- consequences of drinking behavior in the past, including job loss, loss of relationships, career opportunities, and loss of the ability to drive.

- changes in work and the patient’s ability to work.

- changes in the patient’s living situation, as in living alone following a divorce or the need to live in a sober house.

- financial issues and their consequences, which can include loss of residence, confiscation of property and bankruptcy.

All of these have implications for the person’s self-concept and motivation to go forward.

UNDERSTANDING RELATIONSHIPS

Current relationships can be examined, from a variety of perspectives:

- Relationship issues can be explored. The patient’s ongoing relationships may be more or less satisfying as a result of his/her sobriety.

- Old relationships may no longer be sustainable, especially when they have been destroyed by the person’s drinking or when they are dependent on continued drinking in the future.

- Changes may have to be negotiated with members of the patient’s family of origin.

- Relationships with spouse and children may change dramatically, possibly including divorce and loss of custody of children.

- New friendships may develop, through changes in work or living arrangements, or through self-help group participation.

For some patients, drinking may no longer be available to mask or run away from unsatisfying aspects of relationships. For others, it can no longer be used as an excuse for inappropriate, unsympathetic, angry or violent behavior toward the people around them.

These changes provide opportunities to work on interpersonal relationships, which have likely been neglected and remain in a primitive form. This work would include –

- engaging in a more realistic examination of interpersonal relationships.

- attaining a balance between caring about the needs of self and of others.

- gaining increased awareness of narcissistic vulnerabilities and his/her own part in being hurt by others.

- increased recognition of the patient’s impact on others.

- relinquishing narcissistic entitlement and rage

- gaining a broader perspective about his/her own place in relationships, organizations, and the wider context of community and the world.

EXPLORING SEPARATION-INDIVIDUATION

- Many alcoholic families are enmeshed in ways that can contribute to a patient’s urge to drink. These may have to be addressed and modified with the patient and family members. If others won’t change, the patient may have to develop new defenses, possibly by creating distance [not calling mom every day; or not going to family gatherings or moving away].

- Friendships may also be enmeshed, with expectations of involvement and anger and punishment for failure to give what the friends want. These relationships may also have to be re-negotiated or abandoned.

In addition to reducing immediate pressures to drink, greater separation-individuation can also lead to less need to self-soothe following interpersonal conflicts with friends or family members.

INTIMACY

An alcoholic’s relationship with alcohol has to some extent replaced and interfered with relationships with other people [Keller, p.111].

According to Kaufman [1994, pp. 134,139-140] attainment of a high level of intimacy with significant others is a major goal for this phase of treatment. In this area, work can have a goal of improved intimacy with a partner, parents, siblings, children and close friends. The person must work toward increasing intimacy with others and simultaneously build a more autonomous sense of self.

This aspect of the work depends on the ability of the patient and his/her partner to work together on positive changes. It may be a time for an emphasis on couple work, including work on communication and conflict resolution. If improvements in autonomy and intimacy are not possible with the current partner, the patient may need to move on.

MOODS

A person in recovery may experience intense mood swings for a long time, in part because of life changes, and in part because of the inability to hide from his/her moods by drinking or engaging in drinking-related activities. Common emotions include –

- grief over loss of alcohol and related activities and life style.

- grief over opportunities wasted while drinking – for relationships, jobs, or living situations.

- fear of having to face the conflicts and emotions previously avoided by drinking.

These moods and affects can be addressed directly by a variety of therapeutic methods, including –

- direct examination of the moods or feelings themselves, along with their antecedents and consequences.

- exploration of the roots of critical affects such as guilt, shame and rage, with the aim of tolerating them better or re-interpreting situations, and forgiving self or others.

- releasing affect in acceptable ways and in a safe setting.

- re-interpreting past and current life events.

- re-examining the perceived motives of other people.

To the extent that drinking served as a defense, the patient may feel less defended, and substitutes may seem awkward or ineffective. Psychodynamic work can be helpful here, in modifying the substitutes of finding more effective substitutes. To the extent that the patient must also avoid triggers, whole areas of activity may have to be renounced.

TRAUMAS

For many alcoholic people, there are unexamined childhood losses, or histories of trauma and abuse, including physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. As with other post traumatic stress patients, they may have nightmares or flashbacks to traumatic situations, that they have run from, covered over, or denied. Drinking may have helped the patient avoid remembering past traumas and prevented him/her from working through them.

Once a patient stops drinking, early traumas can return to awareness, and he/she can feel unprotected from their impact. However, painful experiences, if faced and worked through, can be managed and their power lessened. This is one function of exploratory psychotherapy. For some patients, specific trauma-related therapeutic approaches [e.g.: Ogden, Minton and Pain] may be necessary.

With adult trauma, there is also the possibility of the patient’s involvement in precipitating it, with consequent guilt nd loss of self-esteem. Examples include drunken fights in which someone was hurt, abuse of others, and drunk-driving accidents. Here the work can include making reparation and finding a path to self-forgiveness.

EXPLORE ALTERNATIVES TO DRINKING

A person who has gotten this far has already made significant life changes: a binge drinker is avoiding binges; a physiologically dependent person has been through detox and rehab and has reorganized life to continue without ongoing alcohol use; a socially anxious person is avoiding parties or going to them without drinking; and so on. Long term change shouldn’t depend only on teeth-gritting avoidance of alcohol but also on finding better ways to move forward. For a person who drank to relieve social anxiety, a better understanding of the sources of that anxiety can lead to more effective ways of getting pleasure from social situations and possibly of findng ways to expand on the kinds of social settings that are enjoyable.

Better self-understanding can lead a patient to a life that is less plagued by the issues that led him/her to drink and is generally richer and fuller, regardless of the person’s drinking style or background. Examination of patient history can provide directions to activities that could once again fill needs that had been renounced, lost, or allowed to atrophy.

EGO WORK

Alcoholics typically have neglected significant aspects of their relationships with themselves, other people, and the larger environment, in the course of their withdrawal into drinking. This neglect can be seen in their difficulties in coping in each of these arenas. Psychodynamic therapy can address these issues, with the goal of increasing the person’s cognitive abilities and self-awareness and acceptance, and of improving his/her life.

Patients in recovery typically need to work on self regulation, including –

- increased capacity for physical self care.

- affect management.

- finding more realistic wishes and goals.

- self-comforting.

- finding value in self and maintaining overall self-esteem.

- renunciation of some forms of immediate reward in exchange for long-term benefits.

The misuse of alcohol is consistent with overuse of several common ego defenses, as discussed in Section 34.

Improved involvement with the outside world includes –

- improve reality testing. Less reliance on preconceptions about the world and better ability to examine and respond to the facts in any situation.

- avoiding emotionally dangerous situations and people.

- more accurate anticipation of consequences and anticipation of dangers.

- better planning and improved judgment.

These issues are discussed in Blackman ( pp 48-58 and 89-93), Blanck and Blanck (1974, chapter 2), Keller, (pp. 110-112), Blanck and Blanck (1979, pp. 219-226), and the Cognitive Therapy literature.

GENERAL EXPLORATION

Whatever the person’s other psychological issues are, they can be more effectively and safely addressed at this time than they could have been earlier in treatment. A therapist must always be aware that change, even positive change, can increase a person’s stress and may in itself need to be examined [See Section 35 ].

It is likely that the patient’s personal history will be a recurrent focus of therapeutic attention, as it tends to be in exploratory psychotherapy generally. The combination of sobriety and exploratory therapy can lead to new awareness.

This can be a time to examine other unconscious conflicts that the patient avoided by drinking, including possible conflicts about intimacy and autonomy, sexual performance, or adequacy as a worker, parent or partner.

An alcoholic may have used drinking to bolster self esteem – to feel smarter, cleverer, funnier, more popular or more connected to other people. A person who is more self aware and stronger is less likely to need alcohol as a support. The patient may already have become more assertive about not drinking but still needs to understand vulnerabilities to other pressures from family, friends and co-workers.

38e. Relapse Risks

A number of alcohol-related issues are likely to appear when a patient has been sober for several months or more, related to the wish for the addiction to be over and to not have to deal with it any more. These include –

- a wish to reduce controls and see what happens.

- a wish to try out controlled drinking, having been abstinent for a while.

- a wish to test out his/her “will power” by facing temptations and triggers.

- the use of drugs other than alcohol, with the idea that because they are not the patient’s drug of choice, they are safe.

- a belief that alcohol is no longer a problem and he/she can stop avoiding people or situations that have been tempting in the past.

- boredom or annoyance with self help groups and the people who participate in them.

The danger of these issues is that the risk of a lapse is great, any time that a problem drinker attempts to vary from abstinence; and a temporary or trial return to uncontrolled drinking can easily lead to a full-blown relapse [see Section 33].

A related issue is the idea that the person was only drinking to self-medicate for a psychological issue, which is now resolved; and that it is therefore safe to resume drinking. However, it is risky to encourage resumption of drinking, because [1] the identified issue may not be completely resolved and could recur, leading to relapse; [2] other psychological issues may also lead to alcohol misuse for this person; and [3] the psychological issue may have been a consequence of drinking, so that a return to drinking could lead to recurrence of the psychological issue and another addictive spiral.

There are some alcoholic people who can reasonable work toward and eventually sustain a pattern of controlled drinking. However, they are difficult to distinguish from others who also believe that controlled drinking is a reasonable goal for them and are at high risk for relapse. Until these two groups can be reliably distinguished, it is safer to recommend continued total abstinence to all patients.

So long as a person is only considering these issues, psychodynamic supportive therapy [Section 37] may be the most effective treatment – understanding motivations, strengthening defenses, and possibly uncovering some relevant unconscious material. Should the person act on these issues, relapse is a risk, and a re-evaluation of behavioral management techniques [ Section 25 ] or adjunctive care [ Section 19 ] may be in order.

If a patient announces a “test of sobriety” in advance and refuses to be dissuaded, then it may be possible to get him/her to load the test in favor of sobriety – by taking along a friend who doesn’t drink, by announcing to others that he/she is not drinking at the beginning of the night, by leaving early, etc. If he/she manages successfully, the experience should be reviewed and processed, to understand what was effective and why. It should be considered to be a step and not proof that the problem is resolved.

If the patient lapses, consider the treatment suggestions for dealing with lapses and relapse in Section 33. If the patient passes the test and is able to go without drinking, it raises other issues, including the patient’s interpretation of success, which should be explored in therapy. For example, it is likely that a patient who is highly motivated to be able to drink moderately or normally will see one successful instance as proof that his/her drinking problem is over.

When a patient reports an urge to drink, it should be taken as possible indicator that treatment has proceeded too rapidly, or that the patient is under other additional stress, and addressed accordingly. [Kaufman, 135-136]. It might be a time to reduce treatment pressures, to try to reduce other stresses, or to consider alterations in adjuctive treatment.

For another discussion of this issue, see Washton.and Zweben, Chapter 10.

38f. Changes in Adjunctive Care

As a patient changes in primary treatment, it may be a time to re-evaluate adjunctive treatment as well – to modify the number of group or self-help sessions the patient attends per week, to put more emphasis on work, family, and other relationships, and to re-evaluate medical issues and modify medications. The general trend in treatment may be toward reducing management aspects of adjunctive care as psychological awareness and self control increase.

When a patient talks about reducing his/her AA attendance, you should consider that the change might be defensive, to avoid facing some new awareness that actually ought to be addressed. Besides exploring the meaning of and reasons for the proposed change, you might also suggest a change in type of participation, possibly involving more step-work. Taking the 12 steps is a process generally done with an AA sponsor and is periodically repeated throughout recovery. Step-work, beginning in intermediate recovery, often can fit well with exploratory psychotherapy, as it encourages active self re-examination. Over time, an active AA participant may go through the steps repeatedly.

If a patient has gone through the twelve program steps and needs a change, then participation in meetings of Adult Children of Alcoholics or Al-Anon might be helpful. However, ACOA meetings are generally more advanced than regular AA meetings, in that there is less focus on sobriety and more on issues of being reared in an alcoholic family. Many new treatment issues can be stirred up by involvement in these groups. Because of that, it often pays to wait until a person has had 3-4 years of sobriety before recommending ACOA or Al-Anon participation.

All aspects of the patient’s treatment are open to revision as he/she changes. This may include an increase in some aspects – increased medication if the patient’s stress level increases, introduction of couple work when the patient is ready, or more individual sessions if a particular issue needs to be addressed more intensely.

A natural change in recovery is a reduction in frequency of attending self-help meetings over time. A therapist may support or oppose the change, but intensity of involvement will be decided by the patient. Ability to maintain abstinence is the primary criterion for assessing the intensity of self-help commitment.

If a patient changes AA participation without discussing it in treatment, you should be suspicious that it involves acting out, possibly preliminary to a relapse. On the other hand, some patients claim to have moved on and no longer need AA participation in order to stay sober. In fact, they may claim that involvement keeps reminding them of experiences that had otherwise left awareness.