-

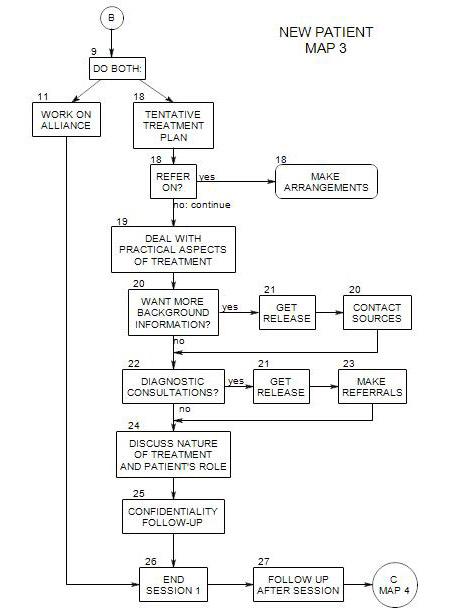

This follows Section 10 on Map 2

At this point, it is helpful have some working hypotheses about the patient. These make use of the information you are gathering to guide early phases of the treatment.

The first diagnosis can be crude, tentative, and incomplete. It includes-

- A preliminary awareness of the patient’s issues, symptoms, and kinds of discomfort.

- some ideas about what the source or sources of the patient’s discomfort may be,

- some idea of what to expect from the patient in terms of cooperation and resistance,

- some ideas about what additional information you need to gather.

Generally it makes sense to think of levels of diagnosis, ranging from symptoms through preliminary or surface diagnosis, to a deeper understanding of the sources of the patient’s problems. We typically want to work from the surface to underlying causes and sources. However, we want to work slowly and thoroughly, and to be prepared to change our understanding as necessary to accommodate to new information.

We should also expect to find multiple sources of the patient’s difficulties, so we aren’t tempted to end the diagnostic process too quickly. In fact, diagnosis typically continues throughout treatment, and new perspectives may appear at any time.

A diagnosis serves other purposes as well. It can aid in giving you a focus when discussing the patient with other professionals.

12a. Multiple Tentative Diagnoses

It can be helpful to start a list of symptoms and tentative diagnoses early on, then refer to it from time to time, to think about changes, tentative or partial treatments, or gathering more information. A blank starter list appears in Appendix B of Section 7.

For example, a patient may admit to having some fears, some depression, some interpersonal conflicts, and difficulty sleeping. To give only one diagnosis might be premature and limiting, any any early treatment is likely to be partial and incomplete.

Symptoms can be connected in ways you won’t understand for a while. Relief from some symptoms can have unpredictable consequences for the patient’s experience of other symptoms and issues.

It is typically necessary to have a diagnosis when dealing with insurance and managed care companies. In this case, a diagnosis helps to legitimize the treatment, and to justify the expense of therapy to third party payers. An insurance diagnosis is relatively specific: the patient is placed in one or more of the categories provided by the International Classification of Diseases [ICD] or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association [DSM]. Without one or more of these labels, you won’t get paid by the patient’s insurance.

Many insurers want a five-factor DSM diagnosis, and it is a good idea to refer to the latest edition of the DSM for guidance. Here symptom lists appear for each of the disorders listed, along with discussions of the disorders and symptoms that distinguish one from another.

Mental Status: