-

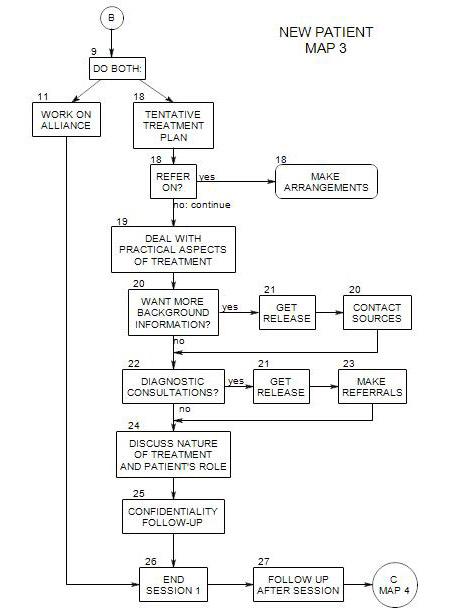

Comes from Map 3

At this point, you have gathered some basic information [ Section 10 ] and decided that outpatient treatment may be helpful [ Section 14, Section 17 ]. You already have a general idea of a direction for treatment. A complete diagnosis is not desirable this early in the process, and would probably be wrong in some significant aspect.

In most cases, the best procedure is to continue working with the patient to learn more. But you probably have a good idea already of productive directions in which to head.

Three other questions are important:

- What additional information do you need, in order to begin work?

- What are reasonable startup-goals?

- How should you proceed, for now?

This of course depends on how much information you have gathered already [ Section 10 ] and the quality of your alliance with the person you are currently seeing [ Section 11 ].

18a. What information do you need, in order to begin?

In an important sense, the work began when the person made the first call. The first session is a continuation of that process, as is every subsequent session.

Probably a better phrasing would be, What else do you need to know in order to have a clear direction for now? This leaves open the likely option that the direction could change at any time.

You need to decide, with the help of your patient[s]:

- who should be seen, for now

- whether formal assessment is needed, and if so, what professional should do it.

- how treatment should proceed, for now, and who should provide it

- what issues or symptoms to focus on, for now

- how you can best gather the information that will help make these decisions

The answers to these questions depend on the patient’s self report, presenting symptoms, and information about the patient obtained from other sources.

In general, you want to learn all you can about the person’s symptoms and issues.

18b. What are reasonable startup goals?

Having goals keeps us in touch with a larger picture. They set the direction of treatment and help us select out the additional information that help us move forward.

You may have a set of goals from your theoretical orientation that you apply to all patients you accept into treatment. These could include-

- increase patient self-understanding.

- replace dysfunctional behaviors with more adaptive ones.

- decide on the balance between therapy and medication.

You may also have goals that you apply to patients with similar symptoms. These could include-

- reduce the likelihood of self-destructive behavior.

- get the patient into AA or NA.

- help the patient learn to talk with a boss or partner.

- focus on the patient’s impulsive actions.

Patients often come with their own goals. This is a good time to ask what the patient wants from therapy. It could include-

- to stop drinking.

- to be a better husband and father.

- to get a job and pay bills.

- to stop having panic attacks.

- ―to get a referral for medication

- to satisfy a judge’s demand for anger management.

A comparison of your general goals and the patient’ goals may suggest a compromise set that can serve as a starting point. It could include-

- helping the patient see AA as a helpful resource in his/her sobriety.

- to explore the relationship between anger and self-destructive behavior.

- to see the connection between anxiety and not speaking up to authorities.

18c. How do you gather more information, if you need it?

Self-report is typically the most valuable information source, at least for adults.

However, people often leave out important pieces of the puzzle, for a variety of reasons, and the picture they provide may be distorted or skewed as well.

Typically omitted or minimized are

- use of alcohol, drugs, caffeine, tobacco

- their own angry or critical provocations of others

- embarrassing things, like binge eating or purging after eating

- impulsive behaviors

- ego-syntonic styles that affect others negatively [being cold, overly logical, clingy, whiney, etc.]

- and a variety of interpersonal behaviors that would be acceptable to others in some contexts but are out of place or insensitive to the people they want to be with

Often the best approach is to keep working with the person, and see what develops. It is not unusual for different issues or perspectives to emerge after a person has been in treatment for a substantial period of time.

For some issues, especially the kinds of things a person will omit or minimize about him/herself, the reports of family members can be very helpful. Some therapists make a point of meeting with a person’s spouse or other family members as a routine part of the first phase of treatment.

Judgments by family members give some information: they know the person very well, but their analysis may be compromised by problems of intimacy and power within the family. [A wife who states that her 40-year-old husband is demented is providing some information, but you can’t be sure just what it is from that alone.] See Section 20 for more on this.

Reports of colleagues who know the patient can be helpful in steering you toward issues to be explored. If such reports can be obtained, you have to decide

- Whether to use them, and if so,

- When, and

- How

You may need to make inferences based on very little and/or indirect information. In this case, it is best to seek confirmation whenever possible.

With some issues, further assessment may be needed, via consultation with a physician, psychiatrist, neuropsychologist, family therapist, physical therapist, specialist in the person’s primary disorder, etc., before you can be clear about a direction.

18c. What symptoms or issues should be addressed, and in what order?

It is not clear how to answer this question, but it is important to consider it. Patients whose issues are not addressed tend to leave treatment and seek alternative ways to address them.

Some principles could include:

- Focus on the things that the patient considers to be troublesome.

- Take up issues when they become apparent.

- Feel free to address issues that you infer, even if the patient hasn’t mentioned them.

- Take up issues according to their riskiness to the patient and others.

- Ask about issues as you think of them, assuming that there is a reason you thought of them, even if you aren’t consciously aware of it.

- Have a list of potential problems, go through it. Such a list could come from any number of sources – your experience with people with similar complaints, a preliminary diagnosis followed by a check of the literature or the DSM for typical symptoms of people with that diagnosis, etc.

How you address the symptoms is also a matter of choice, depending on your training and theory. You could ..

- simply address them as they come up

- present an agenda; Let’s talk about-

- discuss with your patient the choice of issues and/or the order for addressing them.

18d. Who Should Be the Patient?

The patient can be defined in various ways. One way is to distinguish among-

- a single individual [adult, child, adolescent].

- a couple.

- a family.

An alternative way of defining the patient would be:

- Whoever is symptomatic.

- Whoever feels symptomatic.

- Whoever is the source of the problems.

- Whomever you can get to come in.

Ideally, you would work with whomever it took, in order to have the greatest likelihood of making the kinds of changes that are needed. However, there may be a variety of reasons that that approach won’t work.

An individual is generally involved in relationships, and his/her symptoms can reflect his/her own issues, someone else’s problems, or a problem better understood or approached through a larger unit of which he/she is part, such as a couple or family. On the other hand, you may be able to affect family or couple pathology by working with a single member, so long as you expect other members of the family or couple to resist change.

18e. Who Will Be the Patient?

When an individual comes for therapy with individual issues, the choice of patient may be fixed.

Often, however, others are implied or inferred parties to the issues the identified patient wishes to address. In this case, even though only one person appeared for treatment, more effective interventions may require the involvement of other family members.

In part, your choice here will depend on who is willing to be the patient. In a couple, it is not unusual for one partner to be a willing patient, the other not, for a variety of reasons. You may need to define the problem – overtly – as different

from what you actually think it is, in order to have any effectiveness at all.

You may also fear treating one member of a couple, because the other may take your choice as evidence for his/her own lack of a problem. It is not unusual that the one who claims to be normal is a major source of difficulties for the one who is seeking help.

18f. Who Should Be the Therapist?

A number of issues come up in this regard:

- When you have been defined as an intake person or a consultant, sending the patient on to another professional after an initial interview is consistent with the patient’s expectations. In a typical private practice setting, it is not, and the person may be reluctant to go to another therapist after seeing you.

- Availability is important. Your own availability will be contingent on your schedule and work load, the location of your office and the patient’s ability to travel, your fee and the patient’s ability to pay, etc. See Section 19 for more on this.

- If you see the person as needing specialized work that you can’t provide, you may need to send him/her on. You should do what you can to expedite the change. This could include checking the availability of the professional you are referring to, whether he/she takes the patient’s insurance, etc.

- Conflicts, including-

- You see an individual. Should you also see him/her as a member of a couple, or refer the couple on?

- You see one member of a couple or family. Should you see another?

- You have a relationship with someone who wants therapy. Should you see the person or send him/her to someone else?

- If you refer on, you should make it as clear as possible whether the patient will be returning to you after a brief period with someone else, or whether the transfer is for the duration of treatment.