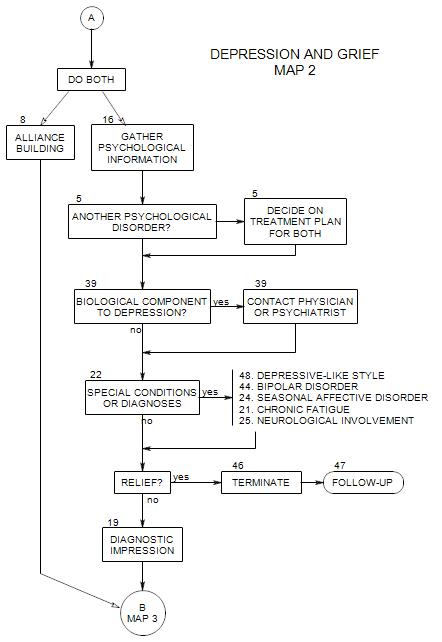

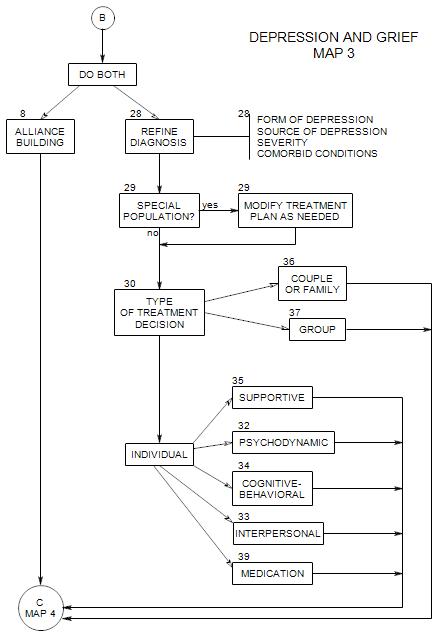

SECTIONS: 5 | 8 | 16 | 19 | 21 | 22 | 24 | 25 | 39 | 44 | 46 | 47 | 48

SECTIONS: 8 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 39

-

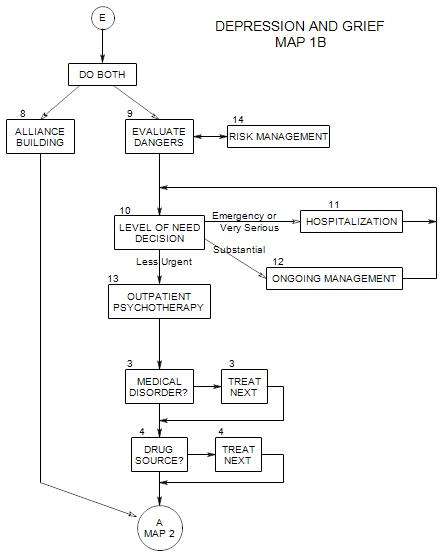

Follows Section 13 on Map 1B

It is important to gather information on medical disorders early on, if for no other reason than to eliminate them as the source of the person’s depression.

Some diseases and disabilities may have depression as their natural side effects, either by affecting biological systems that are directly implicated in depression, or by producing changes that impact on self esteem or ability to cope.

In other cases, the medication or surgery used to treat the disability or disease produces changes that can lead to depression: depression as a side effect, changes in body image or ability to cope, or limits in life options.

On the other hand an individual may have a unique reaction to a particular disease or disability because of its special meaning to him/her, or to limitations it imposes that would not affect others as severely. In this case, the issues may generalize beyond the disease or disability, and psychotherapy may be helpful in dealing with those issues.

If it seems that the person’s depression has a medical component, this is a good time to send him/her for a diagnostic consultation, as indicated in New Patient Section 22 and Section 23.

Even when a medical issue is resolved, a person may remain depressed, for a variety of reasons. There may be another medical disorder; the person may be reacting to medications; or there may be a psychological source to the depression. In any case, further psychotherapy may be needed.

3a. Disease

Depression as a side effect of [a] biochemical imbalances, [b] limitations, and [c] sense of loss

Treat [1] disease first, then [2] reactive depression

Ask about any diseases the patient may have. Then ask about the diseases listed in Section 27. Many diseases are commonly associated with depression, possibly because they deplete patients’ energy, or because they undermine the patient’s optimism through chronic pain or a sense of helplessness and hopeless.

One possibility would be to give a person a checklist of medical issues that could be causing or exacerbating his/her depression; then once he/she has completed it, go over each of the items together.

3b. Disability

Ask about any disabilities or physical limitations the person may have, and how he/she copes with them.

Reduced ability to function can lead to sense of loss, grief, and depression.

Treatment for [1] acute depression; and [2] help coping

Treatments for diseases or disabilities could also have depression as side effects. Obvious here would be surgery that removes a limb of breast and changes the person’s body self-image. Even the recovery period from surgery [forced inactivity, pain medication, reactions of friends and family] can be depressing.

3c. Chronic Pain

Pain and depression are commonly seen as distinct and treated separately, usually by professionals from different specializations. However, there is considerable overlap in the patient population, and people with depression are more likely than others to develop chronic pain. Among other things, depression can increase the pain of headaches, backaches and arthritis. [Turk etal, 2002]

There are a variety of ways that depression and chronic pain can contribute to one another. A depressed person tends to become socially isolated and to focus inward, where the pain is. He/she may have low energy, insomnia and a sense of hopelessness. Ruminating on the pain can increase its power.

A person in pain can limit activities and constantly watch for painful movements, which also limit movement and lead to discouragement and more depression. Activity is distracting. A person who is constantly focusing inward is at risk for focusing on his/her negative reactions and depressed mood as well.

This means that it is important to ask about pain when treating a depressed person, and to consider treating the pain along with the person’s depression and the source of the pain. However, it should not be assumed that treating the pain will be sufficient to relieve the person’s depression.

3d. Personal Medical History

Especially important here is information about previous depressive episodes and whether there have been periods of elation and heightened activity that might be seen as manic.

Physical and psychiatric illnesses, diseases, injuries, drug and alcohol use, surgery, hospitalizations, diagnoses are also important to learn about.

3e. Family Medical History

Here we are looking both for genetic possibilities and for the emotional and cognitive impact that a family member’s disease or disability might have had on the patient.

Look for pain and disability in people that the patient lives with now or lived with in the past, as a clue to his/her reaction to his/her own pain.

The others may also have provided a child with models for behavior and expectations for later life. A girl whose mother went to bed for several days each month, moaning and screaming in pain, may not have the same reaction as she develops, but she can’t remain indifferent to the possibility of menstrual pain and suffering.

Reference: Turk etal.(2002).