2. INTAKE

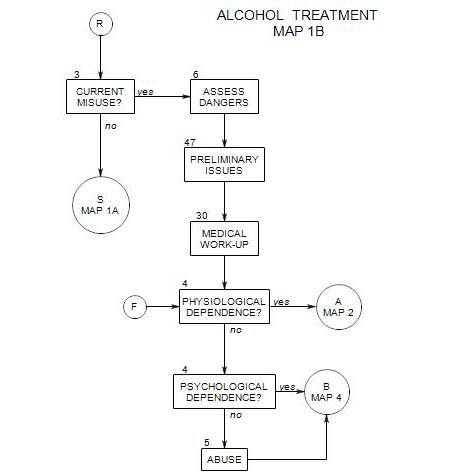

- This section applies to all new patients. An alcohol intake provides the information used to answer the questions of Section 3 [Whether the person is misusing alcohol], Section 4 and Section 5 [Type of misuse], and Section 6 [How dangerous it is]. The current section gives an overview of the intake process and Section 42 provides an expanded list of possible topics and questions.

Here the term “intake” is being used loosely, to suggest an initial gathering of information about a patient. The same general process for assessment and treatment of alcohol dependence and abuse may be used with a new patient or someone already in psychotherapy.

At this point, we are not assuming anything about a person’s self-awareness, motivation for treatment, or willingness to admit a problem with alcohol. A patient is someone who showed up. The rest is to be determined.

2a. Caveat

A possible initial complication is whether the person has been drinking prior to the intake session. Although rare, this does occur, with serious implications for the treatment. The patient’s behavior, judgment and self report may all be affected, and he/she may not remember things you have said [including, for example, the time of the next appointment].

Check the signs of present intoxication in Section 42 if you aren’t sure how to tell. If it seems that you can gather any reasonable information from the patient, you can proceed – but with caution, because

- patient intoxication decreases the likelihood that any data you gather will be accurate

- the person may be fooling him/herself and you about his/her interest in treatment, and to continue may be to collaborate in the self-deception.

- the person may be fooling him/herself about a lack of need for treatment and attempt to enlist your support.

An intoxicated patient becomes the therapist’s responsibility – to make sure he/she gets home safely. It may be necessary to spend a substantial part of the interview time dealing with what will happen after the interview. This can include calling a friend, neighbor or family member to take him/her home safely, confiscating his/her car keys, driving him/he home yourself, or even calling the police. It can be a tough call for a therapist – especially when first meeting the patient. Drunks typically underestimate their level of intoxication and overestimate their ability to drive a vehicle. On occasion, you may agree with the person that what is needed is immediate detox, and make arrangements on the spot to get him/her to a detox facility.

2b. Quality of the Interview

Alcoholic patients often have little apparent motivation to change, partly as a result of their defensive structure and partly because they are afraid to give up their addiction for an unfamiliar approach to life. Therapists have often reacted in ineffective ways to alcoholic patients, by

- treating them as lacking in will power, almost as a sign of moral weakness, and becoming demanding and controlling.

- treating them as unready or unwilling to change [which may be at least partly true] and dismissing them as serious patients [which may be a mistake].

These attitudes may create a self-fulfilling prophecy of failure on the parts of both patient and therapist. There is also a risk that the patient will feel attacked and become defensive in response to it. The more resistant a patient is at the beginning of treatment the less likely it is that he/she will change.

Recent approaches attempt to work with alcoholic patients more cooperatively. Therapists who subscribe to a disease model of alcohol misuse think of the person as out of control, relative to drinking, and work toward a shared goal of managing disease. Behavioral approaches assume that drinking is a learned reaction to certain situations, relationships, emotions, and so on, and work toward helping the person learn better ways of coping. Psychodynamic approaches assume that the person is attempting to deal with internal and often unconscious motives and conflicts, and work cooperatively with the patient to understand those internal pressures as a basis for relieving them. These concepts lead to approaches that engage alcoholics as active participants in their own recovery. Techniques of motivational interviewing [Section 24] are also available to formalize the process of helping patients work toward sobriety. Miller and Hester [2003] review and compare several treatment models.

A first order of business is establishing a treatment alliance, an understanding about the purpose of treatment and a sense of working upon an agreed-upon set of goals.

It is important at the outset to set the frame for treatment. A major component of psychotherapy is the idea that what is said will not be revealed to others. This has the potential for allowing the patient to be more open, and thus to examine issues that might otherwise remain hidden. Confidentiality means that

- no one can overhear what is said in the treatment room

- what is said belongs to the patient

- you may not reveal anything about him/her to others without permission

- no one else has access to your records

On the other hand, a therapist has a moral and legal responsibility to let others know if the patient is planning to or likely to harm them; and a therapist must do everything possible to prevent the patient from harming him/herself.

Patients should be informed of the standard limits to confidentiality, that basic information about session dates and times may have to be passed on to the patient’s insurance company in order for payment to be made. If that is not acceptable, then the patient will have to pay for sessions directly.

2c. General Information from New Patients

Initial issues with any patient include protecting the patient’s safety and dealing with any crisis the person may be involved in.

Following that, intake with most new patients tends to be relatively broad and shallow; you are getting oriented relative to the person and his/her issues. Typical opening questions include “Why are you here?” “How did you get to me?” “What do you expect in therapy?” “Why now?” and so on. People come with their own reasons, and those reasons should be focused on and pursued. In addition to questions about the person’s alcohol use, it is important to ask about psychological issues, medical issues and medications [See Section 8 ].

It isn’t necessary to gather all the treatment-relevant information at this time. It is important to gather enough to move on to the next stage of treatment. If the person continues, there will be ample time and opportunity to learn more. A clear understanding of a person may take several weeks at the usual rate of one or two sessions a week. If the person is withholding important information, it may take much longer.

Certain information should be gathered routinely, including

- name, date of birth, address and telephone number, immediate family and family of origin, symptoms, medical information, and so on.

- background information about drinking and other psychological issues, including prior psychotherapy and drug and alcohol treatment

- signed releases, especially to contact physicians regarding medical issues and prescriptions, to the referring source, and to obtain any report from a rehabilitation center

- information needed to verify insurance coverage and make claims

If the patient’s insurance requires precertification, you need to decide how the case can most effectively be presented to a reviewer, then make the call or send in the form by the required deadline.

It’s a good idea to have a checklist of issues to be covered and a file of printed forms available to cover the information you typically need or want to collect to understand a patient as quickly as possible. This should include both psychological issues and alcohol issues. Section 8 discusses the treatment of patients who have another disorder along with alcohol misuse.

At the same time, you are setting the stage for the person, establishing expectations and beginning a working relationship. With some people, you may want to define the work of the first session as deciding whether to have a second session.

Even when a person comes for psychological, interpersonal or work-related issues, there may be an associated problem of alcohol use. It is important to listen for alcohol involvement, even when the patient doesn’t raise it. Possible forms of relationship between alcohol use and other symptoms or issues include

- A person may attempt to treat a psychological issue with alcohol. Anxious people may use alcohol to calm down. Some people may have a drink in order to fall asleep at night. Drinking may be used by a depressed person to disappear. People with PTSD or bipolar disorder often become alcohol dependent, and so on.

- Alcohol may exacerbate another issue. A person with social phobia may drink to go to parties, and then take physical or sexual risks because of the effect of the alcohol.

- Alcohol may be the source of a psychological disturbance, or exacerbate a previously existing disturbance. At this point, it is often difficult to determine how or how much the patient’s drinking may be involved in his/her physical and psychological symptoms.

- A person’s drinking may interfere with the treatment of other issues, either because it is distracting or such a convenient treatment in itself. For example, the person with a social phobia may become psychologically dependent on alcohol and never relieve the social phobia directly.

If the patient is comfortable discussing alcohol use, you can continue by asking –

- whether he/she is concerned about drinking as an issue.

- what impact drinking has on his/her life.

- whether he/she has goals about changing his/her drinking behavior, and if so, what they are.

Patient information may or may not be complete and accurate early in treatment, including drug and alcohol use. There are many possible reasons for this, including –

- uncertainty about trusting you.

- fear of being exposed and humiliated, criticized or prosecuted.

- fear of having to change.

- poor memory.

- the patient’s mood may affect responses.

- he/she may be attempting to create an impression [of being OK or of needing treatment, or of being earnest, etc.].

Paradoxically, it may help patients trust you and open up if you reassure them that they might not want to be completely open at this point, and they may or may not decide to change. At this time, you should begin to assess the person’s insight about drug and alcohol use, as well as any other disorders he/she may have, along with some indicator of willingness to work on them.

For more details about an assessment interview for alcohol use, see Section 42.

2d. Alcohol Use is a Reason for Treatment

There are a variety of reasons a person might come for treatment of an alcohol-related problem. Although some of these may not seem at first to be about drinking, the connection to alcohol may be direct and obvious, even to the patient. Examples include:

- deteriorating interpersonal relationships, with family, friends, or people in general.

- poor performance at work, including job loss

- poor motivation at home or with longstanding interests.

- poor judgment – financially, legally, etc.

- general mood issues.

- an alcohol-related arrest. This could include a variety of offenses where alcohol is involved: driving while intoxicated, having an open alcohol container in a vehicle, violence or threats of violence while intoxicated.

- another court-related issue, in which there is suspicion of alcohol involvement: harassment charges, family conflict, child protective services, etc.

- referral after inpatient treatment.

- a self-referral because the person wants to stop but is unable to stop without help.

Enough information should be gathered to assess:

- the person’s stated reasons for coming to you at this time.

- current level of use.

- patterns of use (when, for what purpose, how tempted, with whom, etc.).

- history of use, including any legal complications resulting from misuse, including driving while intoxicated, detox, inpatient rehabilitation, or outpatient treatment.

- impact on work and personal relationships.

- possible dangers from use, including effects on judgment, suicide attempts, etc.

- attempts to control use, and their outcomes.

- what functions drinking serves for the person.

- personal resources: family; group membership.

- other drugs: prescription, recreational, over-the-counter.

- history of psychotherapy and/or psychiatric treatment, including diagnoses or problems, and in each case, type of treatment and outcome.

For more suggestions on the interview, including questions to ask, things to avoid, cues about drinking, etc., go to Section 42.

If the person has been referred as part of a court proceeding or for any other non-voluntary reason, it is important to get a release to contact the referring or mandating source. In part, this contact is evidence that the patient is acting in accordance with the court order, and serves the patient’s legal interests. When you make the contact, you may discover that the patient has understated his/her involvement with alcohol, or drugs. There also may be additional legal issues or complications that the person is unaware of or has been avoiding. This in turn can affect your treatment plan, possibly leading to a longer or more intense treatment, and altering the components of treatment.

If the person has been referred by an agency, a hospital, or another therapist, it is usually a good idea to contact the referring source, even if treatment wasn’t mandated. The referring professional can be a valuable source of information about the person that he/she would not volunteer. Here also, you need a release from the person before making the contact.

2e. Alcohol is Not Raised as an Issue by the Patient

Because alcohol issues are so widespread and can be very disruptive to treatment, it is not unreasonable to ask every patient about his/her alcohol use. You may do it directly or wait for an opportunity to arise in the course of getting to know the patient.

Alcohol may also be a reason for treatment when the patient makes no mention of it. A person’s presenting symptoms and reasons are often not the true reasons and seldom the only reasons. You need to probe to fully understand a patient’s motivation for coming, and when you do, you may find alcohol as a part of it that the patient was initially reluctant to discuss. For example, a patient who presents because he argues with his wife a lot may prefer to talk about her unreasonableness and relentless criticisms, and may not mention that she is often upset and critical about his drinking, or not recognize changes in his own behavior and attitudes when he drinks. Indirect evidence for alcohol misuse can also come through consequences of drinking. The issues listed as dangers in Section 8 can be taken as potential signs that a person is sometimes out of control, possibly due to drinking.

Some people may not mention drinking because they see it as so normal and natural that there is no reason to bring it up. (“Everyone does it.”)

There may be a tendency for alcoholic women to be misdiagnosed more than men, by going to a physician for ‘anxiety’; the doctor might give prescription medication for anxiety without ever asking about alcohol use.

There are many possible ways of getting to the issue of alcohol use without just going through a list. You can ask about the patient’s parents, whether they drink or drank, then use that to segue into a similar question about the patient. Asking about the person’s use of leisure time may lead to talk of alcohol use, for some patients.

However, you may not identify alcohol misuse as a problem for a person, if he/she wants to hide it. You also may not identify it until well along in treatment for other issues, or until you meet with the person’s spouse or family.

For more detailed suggestions, go to Section 42 .

2f. Involving Others

It can sometimes be helpful to involve other family members early on in the data gathering phase, for a variety of reasons. Family members –

- may know or remember things about the patient that he/she doesn’t

- may provide a different perspective on the patient and his/her issues

- may give additional information about other family members

- can help to understand the context of the patient’s life and issues

- may evaluate such things as the extent of the patient’s drinking and the seriousness of dangers differently from the patient’s perspective or report

Also, the patient’s drinking may be one part of a larger family problem that needs to be addressed.

Family involvement can be a routine part of the intake process, or in some cases, it can be presented as a routine part of the process. If the patient is reluctant to let you talk with others, that can be a signal that further information about family dynamics or the people in the patient’s life are relevant to treatment.

Early on, it may also be helpful to contact the patient’s physician, to inform him/her that you are seeing the patient, and to gather any information relevant to treatment. It is also often helpful to contact the referral source, to find out why the person was referred and why specifically to you.

These issues are discussed in greater detail in Section 21 and Section 22 .

2g. Practical Issues

If the person is likely to continue, issues of session time and session frequency need to be discusses early on, along with confidentiality.

2h. Fees and Payment

As with the treatment of any psychotherapeutic issue, fee and payment needs to be handled early – soon enough that you don’t get stuck but not so soon that you appear to the patient to be motivated only by payment.

There may be a problem with insurance reimbursement for treatment of alcohol misuse in a private practice setting, so you need to get the patient’s insurance information as soon as possible and clarify this issue. There is seldom a problem with reimbursement for clearly psychological diagnoses, however, and payment is usually based on the first or primary reported diagnosis.