SECTIONS: 5 | 8 | 16 | 19 | 21 | 22 | 24 | 25 | 39 | 44 | 46 | 47 | 48

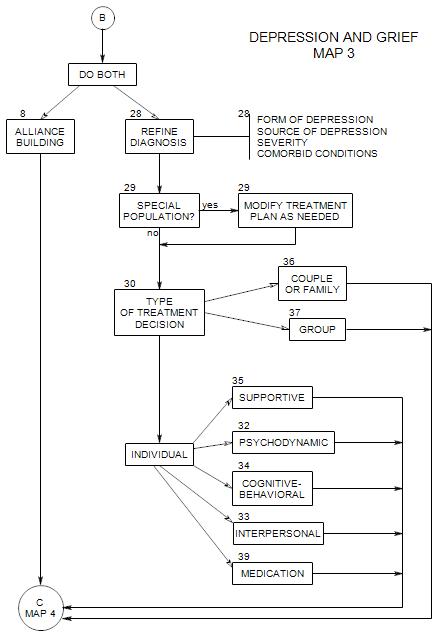

SECTIONS: 8 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 39

-

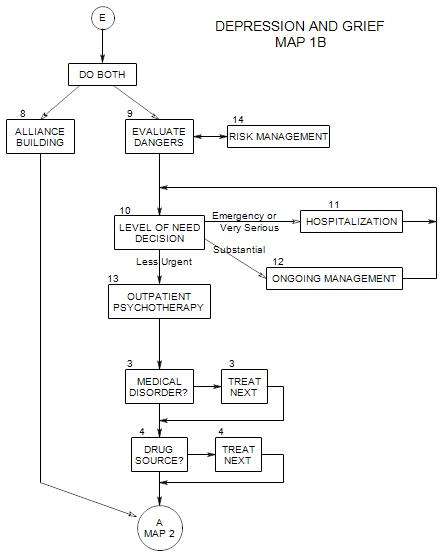

Follows Section 10 on Map 1B

In outpatient psychotherapy, you attempt to help a patient overcome, manage, or adapt to his/her depression without the use of intensive care or a restrictive environment. Most patients who come to a private psychotherapist or clinic are capable of continuing their usual lives and using the treatment as a supplement for dealing with their depression.

Treatment may include helping the patient understand him/herself, providing information, suggesting life changes, and/or working with the patient to coordinate other aspects of treatment.

Because depression is often a side effect – of medical conditions, medications or other disorders, it is important to consider what might be the source of the patient’s depression early on. It is always possible that treatment of something else can reduce or eliminate the depression.

13a. Outpatient Psychotherapy as the Treatment of Choice

For these patients, the external arrangements you need to make are less sweeping than for more seriously depressed people; but they are important.

RISK MANAGEMENT can involve any of the possibilities of Section 14, and possibly others. However, it is generally best to treat patients as co-planners of the case management issues.

For example, you can suggest that he/she call between sessions if he/she feels a need to talk with you; and describe what to expect if he/she makes the call [“You’ll get my answering machine and I’ll call back within an hour”, etc.]

MEDICAL OR PSYCHIATRIC CONSULTATIONS

These can be especially important if…

- the patient has an ongoing relationship with a physician or psychiatrist

- medications are part of treatment

- medical or psychiatric diagnostic work is needed

13b. Outpatient Psychotherapy After Hospitalization or Day Treatment

Treatment here is similar to treatment if the patient has not had inpatient or day treatment, except for some special issues that may come up:

- Thoughts of being severely damaged. Other people in the patient’s family, friendships and work settings may contribute to the patient’s comfort or discomfort around this issue – even silently.

- Reactions to the facility and the other people there.

- Managing the stigma of having been hospitalized. Dealing with questions like, “I haven’t seen you for a while. Were you on vacation?”

- Coordinating treatment with other professionals who may remain involved with the patient.

ARRANGING CONTINUITY OF CARE

This is often initiated by a treatment facility, especially if the patient wasn’t in treatment with you prior to hospitalization. If you sent the patient to the facility and have maintained contact, you may need to be more active.

If the facility hasn’t made contact with you, you can get a release from the patient and make the call, or ask the patient to have records forwarded. Making the call yourself often gives opportunity to speak with a clinician and get information that doesn’t appear on the charts. It also can lead to immediate access to the clinician’s information, while it could take days or weeks for paperwork to get to you.

COORDINATING TREATMENT

Usually this is the responsibility of the primary psychotherapist. That would be you.

13c. Steps in Treatment

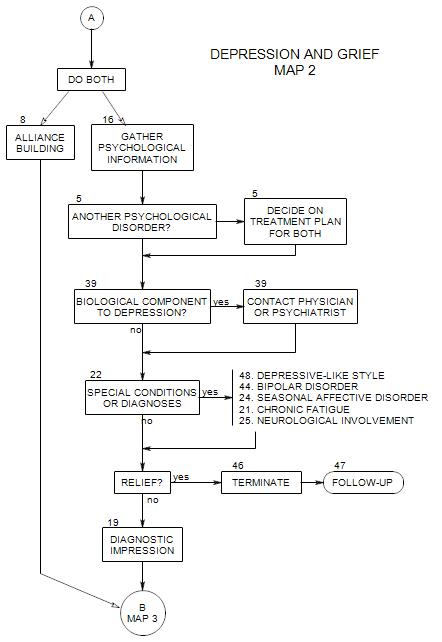

As the patient’s primary therapist, it also becomes your responsibility to be sure that treatment is appropriate and comprehensive. All the steps shown on the maps following the middle of Map 1 must be considered:

- gathering more information [ Section 16 ]

- making contacts [ Section 21 ]

- treating or eliminating special conditions [ Section 22 & Section 29 ]

- refining the diagnosis [ Section 28 ]

- selecting the form of treatment [ Section 30 ]

- choosing adjunctive care [ Section 31 ]

- treating the patient