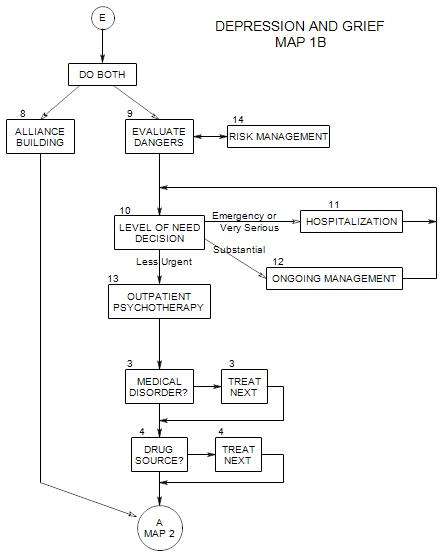

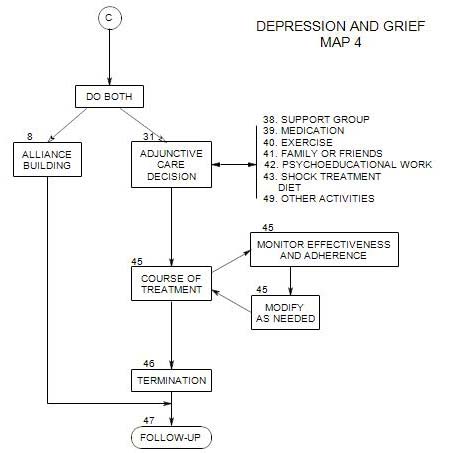

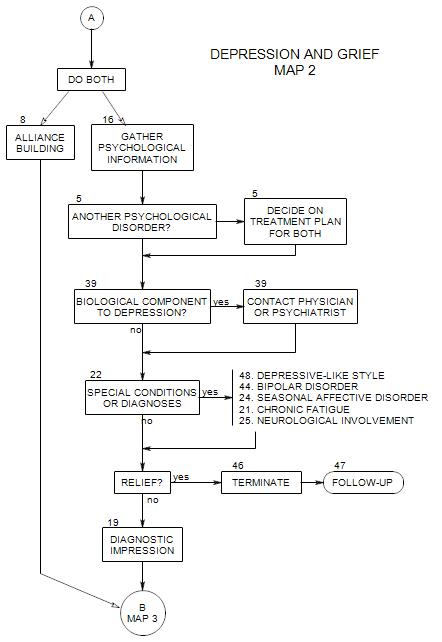

SECTIONS: 5 | 8 | 16 | 19 | 21 | 22 | 24 | 25 | 39 | 44 | 46 | 47 | 48

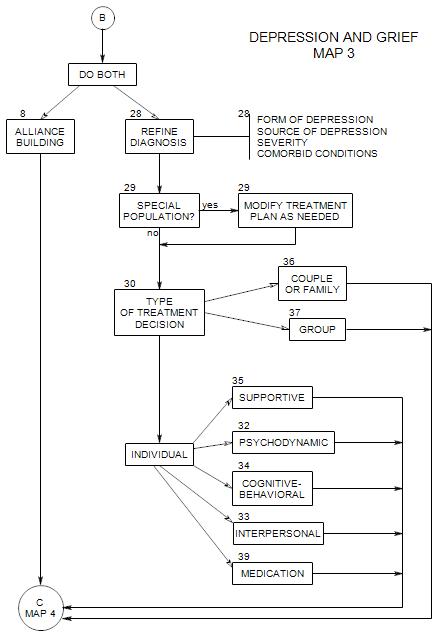

SECTIONS: 8 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 39

-

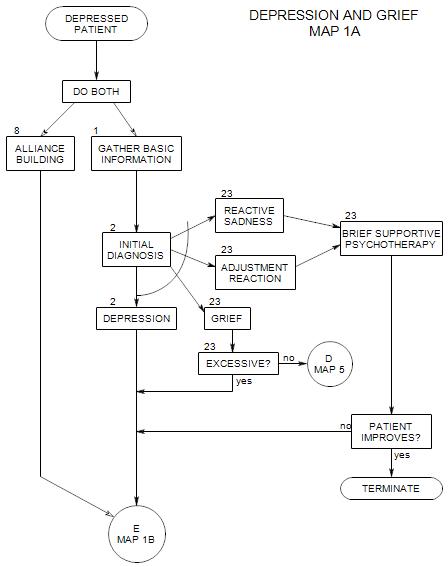

Follows Section 1 on Map 1A.

Here we assume that depression is either a reason that the patient has come to you or it is prominent in his/her presenting symptoms. The patient will most likely be aware of it, in some way or other, and want to talk about it.However, not all people who say they are depressed are really depressed. It could be grief, physical exhaustion, lack of sleep, or low energy level due to a variety of possible causes.

On the other hand, some people may be depressed without realizing it or wanting to talk about it.

2a. First Classification: Type of Reaction

First, we must gather enough information to make a broad diagnosis of

- adjustment reaction

- reactive sadness

- grief

- depression

These are identified in parts c, d and e of this section.

If the person is not depressed, there is generally little likelihood of self-injury or suicide, and unless other issues arise, some form of supportive therapy is usually called for.

If the person is depressed, we need to assess the depth of his/her depression and re-consider the issue of his/her safety [cf: New Patient, Section 10 ].

2b: Data Needed for First Classification:

Briefly, to distinguish depression from the other diagnoses:

- Ask about a precipitating event. If the person is reacting to a loss or change of circumstances, the diagnosis is more likely to be reactive sadness, adjustment reaction, or grief.

- Alternatively, ask about a time prior to these feelings. This may help to identify a precipitating event.

- Look for a loss of self-esteem, in the form of a sense of worthlessness, unimportance, meaninglessness, etc. as evidence of depression.

- Ask yourself whether it seems likely that the person will be able to pull out of his/her state without help, or whether treatment is necessary. Typically we expect that a person experiencing normal grief, reactive sadness or an adjustment reaction will eventually get better on his/her own. A depressed person is much less likely to improve without help.

In order to decide which of these reactions the patient is experiencing, we need to know

- How he/she experiences it, in his/her own words. When he/she gets stuck, you can ask questions. What does it feel like? What times of the day? How much of the time?

- How long has he/she felt this way?

- How or when did it begin? Did it begin abruptly or slowly? What were the first symptoms?

2c. Grief, Reactive Sadness or Adjustment Reaction

These disorders have in common

- a patient’s reaction to an identifiable stressor in the environment.

- depression as a possible consequence.

- treatment focus on coping with a changed environment or changed self rather than primarily on the depression or the patient’s internal reasons for the reaction.

Grief and reactive sadness are generally reactions to a significant loss – loss of someone or something that is emotionally significant to the person, such as…

- a family member or close friend.

- a body part.

- ability to function in an important way [as in loss of hearing to a musician] [or an unexpected pregnancy to a competitive athlete].

- goals or ideals [disillusionment with a leader found to be flawed].

- financial loss [one’s job is excessed].

Of these, reactive sadness is generally applied to reactions that are mild, appropriate, and time-limited without interventions. Grief is used to describe a stronger reaction with broader implications.

An adjustment disorder is a strong, depressive-like reaction to external stress that could come from many places, including…

- a move to a different culture.

- marriage or divorce.

- birth of a child.

- change of job responsibilities or job supervisor.

If you offer another session at the end of an initial diagnostic session, a person with reactive sadness or a mild adjustment reaction may refuse. If not, a session or two might be useful, to reassure the person or give some hints on integrating the setbacks into everyday life. Additional sessions may also uncover other issues that should be addressed, possibly changing the patient’s diagnosis in the process.

On the other hand, if you offer another session and the person accepts, especially with appreciation or relief, then more may be going on than you have realized. In that case, diagnosis should be deferred until you can better understand what the person is dealing with.

For more detail, go on to Section 23.

2e. Depression

Depression involves some of the same feelings: sadness, despair, hopelessness, etc., along with other symptoms listed below. However, it is always excessive, relative an independent appraisal of the person’s life circumstances or provoking situation. We want to determine what to do to help him/her achieve a more appropriate interpretation or reaction to his/her actual life.

Typical depressive symptoms include:

- feelings of sadness; possibly, crying without apparent reason

- the appearance of sadness, depression, or anger

- a sense of hopelessness

- feelings of helplessness

- lack of a feeling of well-being

- selective attending to negative events or negative aspects of events

- decreased sex drive

- increased sensitivity to criticism

- guilt

- poor self esteem

- feelings of worthlessness

Other, atypical symptoms may mask an underlying depressive process. They can include

- self-dramatizing attempts to attract attention

- intense mood swings in response to others’ behavior

- somatizing

- drug abuse

- alcohol misuse

- bulimia

- feeling worse in the morning

- delinquency or crime

Depression is

- stable: “Things are never going to get better.” The patient believes that he/she can’t be helped.

- internal: “It’s all my fault.” The patient is an awful person. Guilt.

- global: “Everything is bad”

2f. Degrees or Levels of Depression

Mild depression can also include

- anxiety

- frequent changes in mood

- low energy, lack of motivation

A more seriously depressed patient can also have

- loss of social interest

- difficulty concentrating or making decisions

- chronic fatigue; listlessness that can approach total immobility

- difficulty accepting positive feedback and support

- chronic pain

- insomnia or excessive sleep

- a general loss of interest in life

- loss of appetite or increase in appetite

- insomnia or hypersomnia

- slowed thinking and movement “psychomotor retardation”

- irritability or agitation

- physical symptoms such as headaches, backaches, constipation or upset stomach

- suicidal ideation

A seriously depressed person may attempt suicide, either actively or passively, and may be successful. There is also a possibility that the person will distort reality, a psychotic process either underlying the depression or occurring as a consequence of it.

2g. Diagnostic Reactions to Patient

You may feel depressed, anxious, hostile, or awkward in reaction to a depressed patient. This can be induced by the patient, and may be a common reaction of others to this person. The degree to which you have these feelings can be an indicator of the strength of the patient’s depression. Your reactions can also suggest something about the patient’s defenses [eg: denial may be frustrating] or personality [e.g.: a patient who connects too quickly may have a dependent personality],etc.

2h. Psychometric Evaluation for Depression

Three scales have wide acceptance as being useful in diagnosing depression

- The Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders Scale [SADS]

- the Beck

- the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression

- The Patient Health Questionnaire

2i. References:

Goldberg. (1995, chapter 5, pp.52-67 and Ch.7, esp.pp. 82-83)