SECTIONS: 5 | 8 | 16 | 19 | 21 | 22 | 24 | 25 | 39 | 44 | 46 | 47 | 48

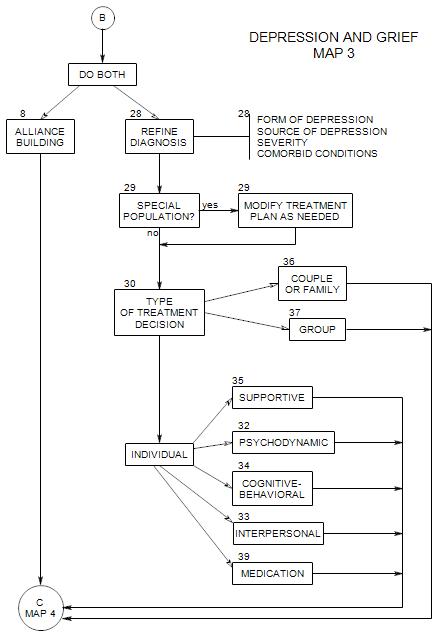

SECTIONS: 8 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 39

-

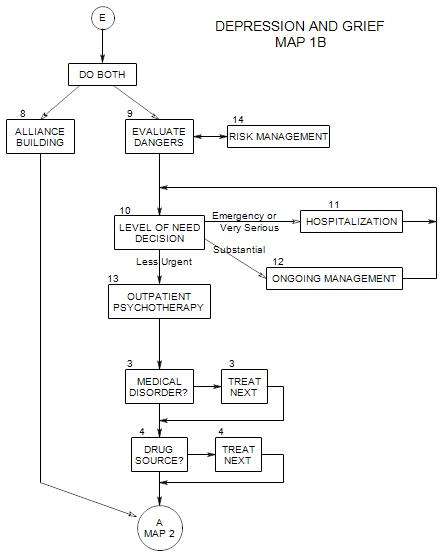

This follows from Section 13: Outpatient Psychotherapy on Map 1B

14a. Phone Calls Between Sessions

These can be very helpful in a time of relative crisis. In fact, a telephone call in time of special need can be a life-saver. Regular calls between sessions can help some patients keep going. If you welcome the calls and stay strictly to therapeutic issues, patients rarely abuse the option.

The offer of extra calls can be made formally, “Can you call me Thursday between 5 and 6, to let me know how things are going?” or informally, “I’ll be around all weekend. Call if you need to.”

Some patients may need two or three sessions a week for the first few weeks, and manage with weekly sessions after they are further along in treatment. Others may need more sessions in times of crisis, and return to fewer sessions when the crisis passes.

Greater frequency may require a sales pitch to patient’s managed care company, generally in the form of patient risk and the alternative of self-destructive behavior or a need for inpatient treatment.

14c. Contract Not to Hurt Self

Effectiveness depends on a good initial alliance. You need to believe that a patient who makes a contract not to hurt him/herself will actually honor that contract.

Such a contract may actually increase patient involvement in the treatment process, by demanding that he/she be an active participant and not just a person you are treating.

Contracts are usually informal, and must feel personal to the patient. If you pull out a legal document for the patient’s signature, he/she is likely to infer that you are actually protecting yourself and not him/her, and that could increase a sense of alienation.

You might say something like, “Can you agree that you won’t do anything to hurt yourself before our next appointment?” His/her answer to the question will lead you to a follow-up of some kind. If he/she says “yes” you might go on to explore things he/she could do [like a phone call] if he/she gets very depressed. If he/she says “no”, you may need to talk about hospitalization or another management option.

In either case, this approach tends to engage the patient’s thinking and planning in managing impulsive emotional reactions. At some point, you might follow up with more probing questions, like “What might lead you to consider suicide?’ and “How can you deal with that, if it happens?”

14d. Involving Family and Friends

If the patient was brought in by a friend or family member, that person’s involvement in the treatment might be essential, for a variety of reasons, including…

- the patient may be very dependent on that person.

- the patient may be too depressed to drive him/herself.

- the other person may be very controlling and contributing to your patient’s depression; etc.

You may have to make an immediate decision about whether to see the patient alone or with the other person, at least for the first session. One possibility is to split the session: see the two together for a while, then ask to see the patient alone. While the other person is out, you can discuss with the patient whether the other person should be a regular participant in the treatment. When the other person returns to the session, you can include him/her in the discussion.

If you decide to see the patient alone, it still remains possible that outside people can be helpful. The patient may be able to identify someone else who could be helpful in case of emergency, someone to talk with between sessions, someone to drop in and help with things that a physically disabled patient can’t do for him/herself, etc.

You might suggest working with the patient’s spouse for one or more sessions…

- if the patient has a problem coming to sessions.

- if you don’t trust the patient’s level of self-honesty or self-awareness.

- if you need an ally in keeping the patient from self-destructive behavior.

- if the spouse appears to be contributing to the patient’s depression.

You may need to involve the patient’s family, if it appears that this person is an outcast, a scapegoat, or in some other way serving the needs of other family members by being depressed.

It is good to have a list of these available before the patient arrives, and offer them to a seriously depressed patient as a resource.

However, you might expect a new patient to perceive this as rejecting, so some explanation needs to be made [that you will be out of town, you are unable to get calls at night, etc].

This is a common route to a psychiatric ward in a hospital. See Section 11.

Have a list of psychiatric wards and associated emergency rooms, possibly staff you know. Call ahead for bed availability when making a referral.