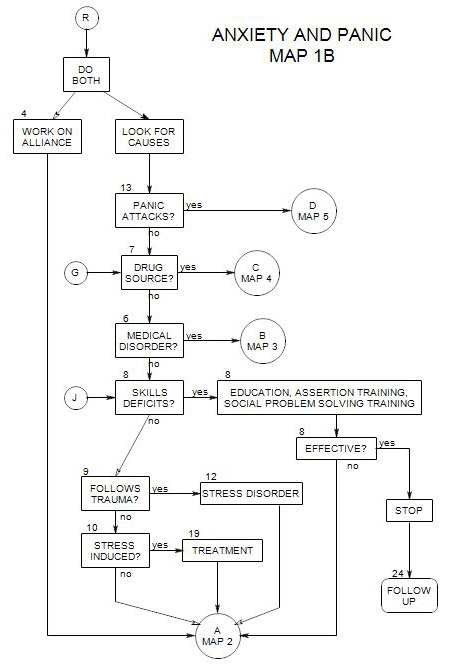

SECTIONS: 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 19 | 24

-

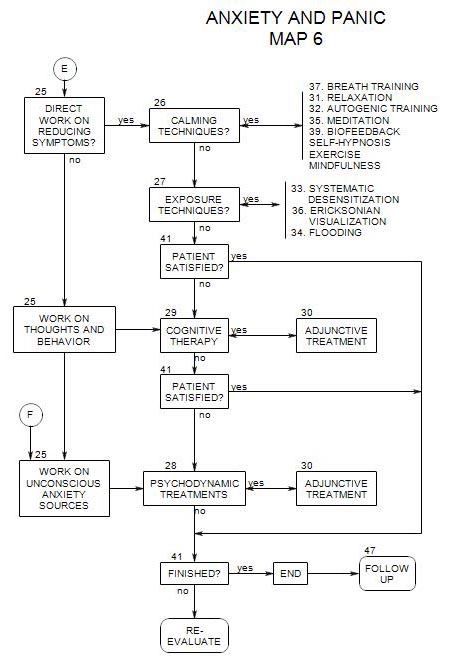

Follows Section 28 and Section 29 on Map 6

Whatever treatment is primary, others can be adjunctive, with the possible exceptions that cognitive therapy is typically a primary treatment and it is difficult to imagine psychodynamic therapy as adjunctive to any other.Here major groups are discussed. Greater detail can be found in the specific sections addressing each technique.

30a. Calming Techniques [ Section 26 ]

Calming techniques [relaxation, meditation, autogenic training, exercise, yoga, etc.] provide overall reduction in the stress reaction without focusing on specific symptoms or their sources. Because of their broad effect, they can serve as adjuncts to a variety of more targeted approaches (Lehrer and Carr, 1997, p.84).

Calming techniques may be valuable in dealing with some of the symptoms associated with excessive anxiety, such as-

- psychosomatic problems involving neuromuscular tension, such as tension headaches (Lehrer and Carr, 1997, p.84).

- somatic conditions affected by autonomic nervous system activity, such as hypertension, asthma, or irritable bowel syndrome.

- worry, insomnia, or excessive ruminations.

In learning a calming technique, a person learns how to reduce internal tension at will. This increased sense of self control helps reduce anxiety also (Linden and Lenz, 1997, p.145).

30b. Medication [ Section 38 ]

In general, the purpose of medication is to reduce the intensity of symptoms, making them more manageable. With anxiety issues, medications are not typically seen as cures, although they may suppress the symptoms for a long enough time that the person can obtain relief through other treatments, life experience, or change of circumstances.

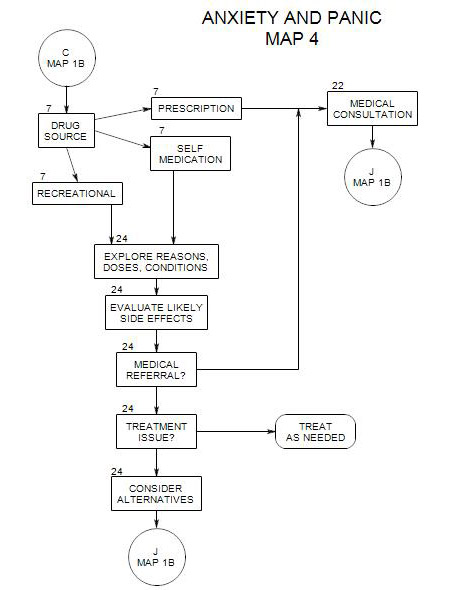

Many issues should be considered before making a medication referral (Beitman and Saveanu, 2005, pp. 418, 419), including-

- the severity of symptoms, how disruptive they are to the patient, and how likely it is that medication will reduce them to manageable levels.

- the goals of treatment.

- the treatment setting and your ability to treat effectively without medications.

- the likelihood that medication will increase the effectiveness of psychotherapy.

- the patient’s other [-than anxiety] psychological or medical issues, and the possibility that a particular medication will also treat the other disorder[s].

- possible interactions with other medications that the person is taking.

- the likelihood that medication will be too effective, reducing the patient’s motivation to work on transformative treatments.

- risk that the patient will become addicted to the medication.

- a patient’s fear of medication and unwillingness to try any.

- the patient’s transference to current therapist and likely transference to prescribing physician as a possible enhancing or disruptive influence.

- your ability to work effectively with the patient’s prescribing physician.

Making the Medication Referral

Medication can have many different meanings to patients (Almond, 1997, pp. 172-173), and you should be careful in making a medication referral. These can include-

- resentment at needing it

- fear of becoming dependent on the medication

- an inference that the person is sicker than the therapist is saying, or that the person referred for medication is the crazy one in the couple or family. This can be especially tricky in couple work, if the non-symptomatic partner is also denying a part in the couple issues.

- a sense that the therapist is trying to pass the person on to someone else

Because of these possibilities, it is important to clarify the need for the referral, and the meaning to the patient of being referred (Beitman and Saveanu, 2005, p. 426).

Reasons for contacting the physician first

Possible reasons include-

- letting him/her know that your patient is coming

- discussing the person’s needs and symptoms.

- discussing side effects of potential medications, if you know what they might be.

- establishing or maintain a working relationship with the physician (Beitman and Saveanu, 2005, p.431).

Reasons not to contact the physician first

- Your patient is going to a clinic and doesn’t know who will be treating him/her.

- It might appear to your patient to be infantilizing.

Follow-up on a medical consultation

It is valuable to most patients to have a discussion about medications after they are prescribed. Some physicians just don’t discuss medications with patients, and some patients don’t ask or don’t push for answers. Other physicians won’t talk to a patient about side effects, lest the patient be overly alert to reactions that he/she would otherwise not notice. This strategy can backfire, if a patient has an unanticipated reaction, thinks it is risky and idiosyncratic, and discontinues the medication before it can be effective.

Some side effects can be handled by changes in diet or by other medications. Drowsiness can sometimes be handled by taking medication at bedtime; insomnia by taking it in the morning.

You may also want to discuss the possibility that the medication could be ineffective. (Beitman and Saveanu, 2005, p.426). Then the psychotherapy is less likely to be devalued if the medication doesn’t meet the patient’s hopes.

Having the discussion includes medication within the scope of psychotherapy, demonstrates your knowledge, offers reassurance to the patient, and anticipates the need for later adjustments to that aspect of treatment.

On the other hand, there is always a danger that patients will credit the medication for any improvement in their condition, rather than take credit for their own work (Linden and Lenz, 1997, p.145). If you have discussed the possible reactions, whatever happens will not reduce your credibility with your patient, and your patient will be more able to keep the effect of the medication in perspective. Patients may need reminders of their own successful actions in managing their anxiety and reinforcement for their successes. Giving the medication too much credit can foster dependency on the medication and the physician prescribing it.

Ongoing Medication Follow-up

It may pay to ask the patient about taking his/her medication and perceived effects from time to time, as non-compliance is a major source of treatment failure. If the person is not continuing or managing on his/her own self determined regimen, it can be a basis for further discussion about treatment goals, control issues, patient expectations, etc.

It may be a good idea to track some patients’ other medications and responses to them as well, as you may be the only professional who is regularly available to discuss them.

30c. Choices Among Adjunctive Treatments

By contrast, the use of medications generally doesn’t lead to a sense of control over oneself and one’s symptoms. Because of this, calming techniques are often preferable to medications (Linden and Lenz,1997, p.145).

Medications should be used cautiously, because of side effects, such as-

- possible interactions with alcohol.

- a high relapse rate if used without psychotherapy.

- a tendency of patients to attribute any positive changes to the medication and to forget or ignore the work done.

- a tendency for patients to accept the need for medication and not engage in other, more effective or permanent work