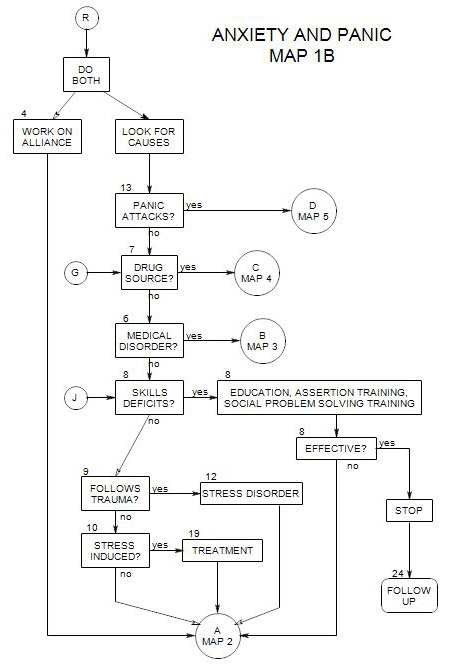

SECTIONS: 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 19 | 24

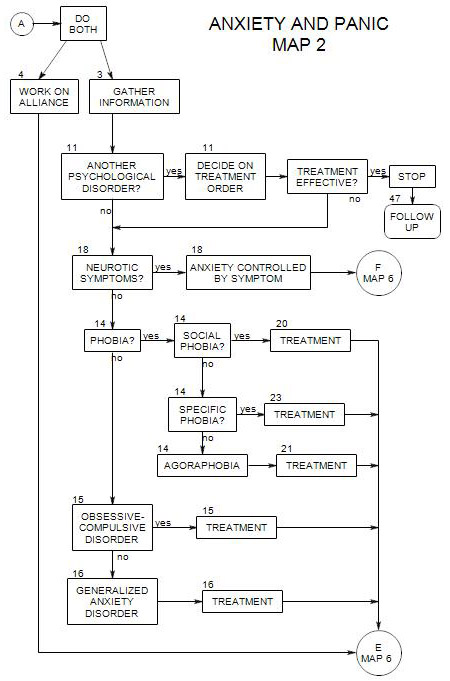

- Follows Section 15 on Map 2

16a. Symptoms and Diagnosis

We use this diagnosis to describe a person who has excessive anxiety about a wide range of real or imagined situations or events.

The anxiety is diffuse, and not usually related to specific objects or situations. However, people with this diagnosis may also have simple phobias [which are more focused] and/or social phobia.

The person may worry about many of the same things as other people: jobs, family, money. He/she is more likely to worry about sickness and health than other people, as well as general issues, such as being criticized, being anxious, being unable to cope. He/she is likely to focus on dangerous and threatening situations more than most people do and tend to see them as uncontrollable.

The generally anxious person tends to expect the worst; but the worst seldom happens, and his/her belief that he/she has somehow staved off disaster by worrying about it is constantly reinforced.(Borkovec and Roemer, 1996, p. 84)

A person with generalized anxiety may also have a variety of vague and/or somatic complaints, including-

- irritability.

- restlessness.

- constant vigilance and scanning.

- sweating, heart pounding, frequent urination.

- chronic fatigue.

- difficulty concentrating.

- muscle tension.

- difficulty sleeping.

The pattern of worry and anxiety is chronic, possibly lifelong. The DSM uses a cutoff of six months or more in applying this diagnosis, in part to distinguish it from adjustment reactions. If the person is anxious in the face of time-limited life stresses, it may make sense to place greater emphasis on adaptation or environmental modification strategies than on the treatments typically recommended for generalized anxiety disorder.

16b. Comorbid Conditions

Additional issues to watch for include

- phobias or social phobia ( Section 14 )

- panic attacks [ Section 13 ].

- depression. This could happen as a reactive sense of being overwhelmed and helpless in the face of pervasive and catastrophic dangers. Treatment for anxiety could reduce depression as well.

- mood disorders.

- substance abuse- especially alcohol – as a form of self-medication.

- psychotic disorders.

- stress disorder ( see Section 9 ).

16c. Treatment Approaches

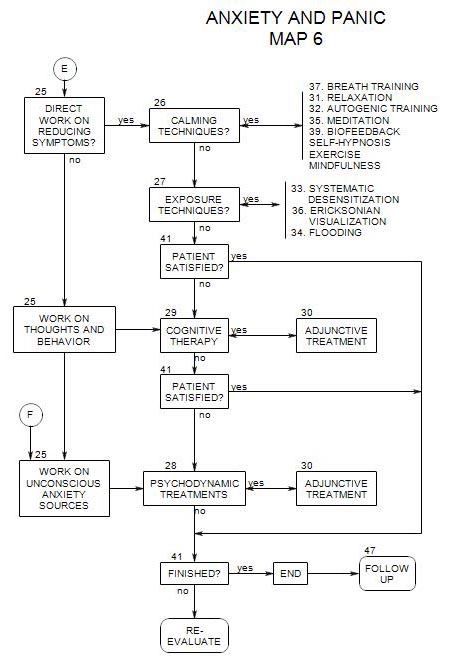

If you see the person’s anxiety as a pervasive issue that should be treated as primary, or if your goal is to reduce the anxiety as much as possible without delving into deeper issues (Section 25 ), then symptom reduction is the direction of choice.

If you see the anxiety as a whole-person character or personality problem, or if symptom reduction therapy has been ineffective, then psychodynamic therapy may be the treatment of choice (Section 25)

Calming Techniques

If symptoms are mild, then calming techniques [ Section 26 ] can be helpful:

However, if the person also has a more intense comorbid condition, you should probably avoid the relaxation therapies, as the procedure may lead to an increase in symptoms – flashbacks, for instance – without an effective approach for processing them. This could in turn cause the person to think that the therapy is making things worse, and lead him/her to abandon treatment.

Exposure Techniques are in general probably not helpful for GAD, because it is difficult to find specific situations or objects to focus on.

Cognitive Treatment, which focuses on thinking, beliefs and attitudes, can be of value. Borkovec and Roemer outline a cognitive approach for GAD that applies coping strategies to stresses produced in-session (See Section 26).

Psychodynamic Therapy

It may be helpful to look at some of the following issues within a psychodynamic context:

- history of trauma in childhood, leading to poor coping skills or expectations of danger.

- poor tolerance of ambiguity and uncertainty.

- difficulty determining when a situation is safe – which can lead to a need for constant vigilance (Mineka and Zinbarg, 2006).

- belief that worry helps avoid dangers (Mineka and Zinbarg, 2006).

- superstitiousness.

- attempts to control one’s thoughts.

- incomplete processing of the situations worried about.

16d. Diagnosis

For formal reports and third party payers, use 300.02 with DSM IV and ICD-9-CM. Use F41.1 for ICD-10-CM and DSM V.

16e. Adjunctive Treatment

With Cognitive or Psychodynamic Therapy as Primary

Calming techniques [ Section 26 ], such as relaxation techniques or autogenic training can be helpful in reducing the person’s overall level of arousal, as well as giving the person a greater sense of control over his/her thoughts and emotions. (Linden and Lenz, 1997, p. 141] With greater control, a person can find variations in his/her experience of anxiety, providing greater opportunity for cognitive or psychodynamic work. (Linden and Lenz, 1997, p. 142; Lehrer and Carr, 1997, p. 84)

If there are no associated panic attacks, an exercise program can also be helpful as an adjunct. If the person also has panic attacks, exercise may lead to the kind of internal stimuli that symbolize a panic attack, and possibly even bring one on.

With All Approaches

For some patients, adjunctive treatment ( Section 30 ) with an SSRI may be helpful (Preston, O’Neal and Talaga, 2002, p. 104)