SECTIONS: 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 19 | 24

-

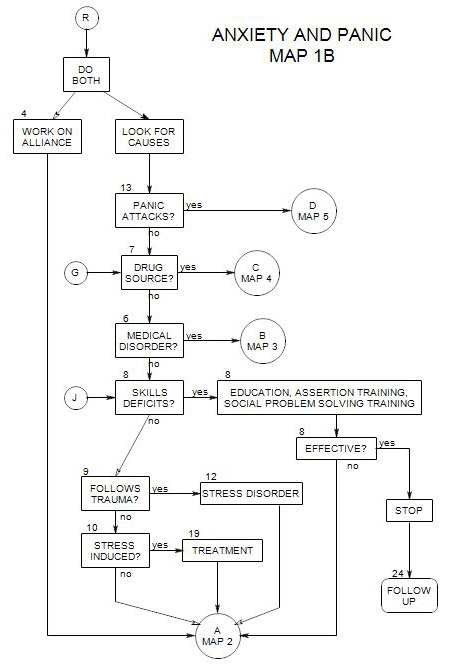

Follows Section 6 on Map 1B

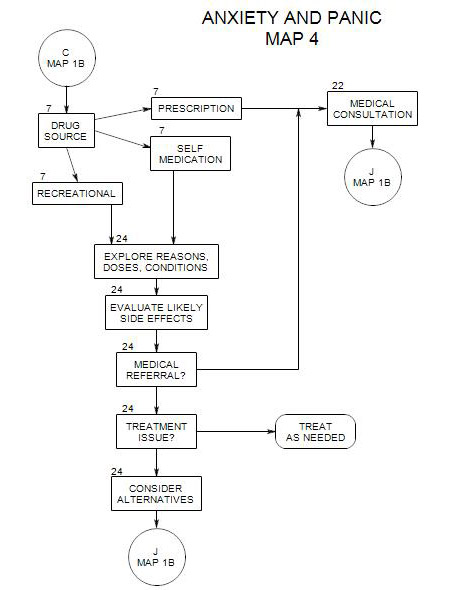

This section coordinates with Map 4. If there is cause to suspect a prescription medication as the source of the person’s anxiety symptoms, then you should refer for a medical consultation [ Section 22 ]. If you suspect self-medication or recreational drugs, you should explore the issue [ Section 24 ] and decide whether to treat the issue now, as a therapy issue, refer for a medical consultation [ Section 22 ], or make note and continue at point J of .

7a. When and How to Ask

It is best to consider possible sources of anxiety early on in the process of working with a person, so you don’t waste time and energy attempting to treat him/her with psychological tools when the source is chemical.

An ideal time is probably right after the person has described his/her symptoms. Then it may be possible to link details of the person’s symptomatology with known side effects of medications and recreational drugs. Even though the drug itself may not account for the full range of a person’s symptoms, it may contribute to them.

One possible way of opening the subject is to wait for the person to mention drug use. Alternatively, you simply say that you need to rule out drugs as a source of the person’s symptoms, and work from a checklist. You can also ask for the information in an open-ended format.

Generally, you will need to know every prescription, over the counter, and recreational drug that the person uses, along with doses, frequency, reasons for use, and the person’s reaction to it.

It is often helpful to ask the person to keep track of each drug and reactions to it for a period of time. It may also be helpful to check with person’s prescriber for known reactions, if you are unsure.

7b. Current Prescription Medications

Drugs can be used for one purpose, treatment of a medical or psychological disorder, and have an unintended side effect of causing anxiety, either directly or indirectly, by causing side effects that in turn make the person anxious.

Ask about all medications the patient may be taking, doses, frequency, and what for. Check the list in Section 49 for a list of some that are known to produce anxiety. Also check medical references. Because medications are carried to their intended internal targets in the person’s bloodstream, a medication can have multiple effects on organs other than the one intended. Some of those other effects can be substantial and disturbing to the patient.

For a more complete listing, see PDR Drug Guide for Mental Health Professionals [3rd ed.], which has an extensive listing of drugs with anxiety among their side effects and another table of side effects by brand [Section 5, parts 1 and 2].

This is also an opportunity to check with the patient’s physician about known side effects of any medications not on the list.

If medication is a likely source of a patient’s anxiety, there are several treatment possibilities that you or the patient can discuss with his/her physician:

- Change to another medication with similar effect on the primary condition being treated but which may not lead to anxiety.

- Consider a change of dosage that will reduce the side effect but have the same primary effect.

- Ask about daytime drowsiness if a sedating medication is taken in the morning. The inability to “get moving” may lead to anxiety about completing the day’s tasks. One solution could be to take it at night.

- Ask about sleep if an energizing medication is taken in the evening. Lack of sleep can lead to anxiety. Perhaps the medication could be taken in the morning, or at night in combination with something else to induce sleep.

- Add a second medication to treat the side effects, including anxiety.

- Accept the anxiety as a necessary side effect and find a way to live with it.

- Look for other sources of anxiety that may be compounding with anxiety induced by the medication. If they are reduced, it may be possible to lower the patient’s overall anxiety to a tolerable level.

7c. Over-the-Counter Medications

Many people attempt to treat physical and psychological symptoms without professional advice, because they-

- consider the symptoms not to be serious enough to require professional help.

- don’t trust physicians.

- think they should be able to handle things themselves.

There are risks here. People may-

- be unaware of the long-term side effects of certain over-the-counter preparations, or of their interactions with other medications or alcohol.

- exceed the manufacturer’s dosage recommendations and overdose, because the drug is ineffective or only partly effective at the recommended dose.

- assume that the drugs are harmless, because no prescription is needed.

Some common over-the-counter preparations that can have implications for the patient’s mood include [1] cough and cold medications; [2] antihistamines; and [3] melatonin.

Many over-the-counter preparations are combinations of drugs and additives. Some components can have side effects, cause allergic reactions, or interact with other preparations [e.g.: milk products used as binders in medications may lead to an allergic reaction; caffeine included to enhance absorption may contribute to a person’s overall caffeine intake].

7d. Recreational Drugs or Alcohol

People use a variety of recreational drugs, for a variety of reasons, commonly to create a feeling or to manage their moods. There can also be social pressure to use or to avoid drugs, depending on a person’s reference group.

Some drugs may induce short or long term anxiety. For each drug that a patient uses, you should ask about-

- the desired effect [e.g.: to feel better; to stop feeling; to go to sleep.

- the actual effects.

- the quantities used.

Be aware that patients typically under-report use of recreational drugs and resist attempts to limit them. You may not be able to get an accurate picture of use. It may be helpful to explain the reasons you need this information, namely that drug and alcohol use can affect mood. You can try some disclaimer, such as saying that you know it can be embarrassing or that you need to know in order to diagnose and won’t judge, etc. You may also need to remind the patient that what they say is confidential and won’t be reported to authorities except under specific situations. Those situations depend on where you practice, but typically have to do with danger to self or others. You may need to obtain the information from family or friends.

Because of social pressures associated with drug use, a serious assessment should ask about use by family, friends, co-workers and others, and any pressures that the person may be experiencing to use or not to use.

ALCOHOL

Drinking can cause

- hangovers.

- long-term mood effects.

- loss of self-esteem, depending on your patient’s feeling about needing to drink, about being hung over, etc.

- effects on work, relationships, etc.

- increased risks of accidents and lapses of judgment.

- more serious consequences.

All of these can lead directly or indirectly to increased anxiety levels. For example, a person who drinks at night may be hung over at work the next day, perform inadequately, become anxious about work, and “need” to drink the following night.

You should generally ask about the frequency of drinking, circumstances, what a person drinks, and how much. You should also generally expect people to understate the amount they drink. Asking once may not suffice. You may get different answers on different occasions, depending on the context of the question and the person’s comfort with you.

Note that alcohol may reduce the effectiveness of some medications, such as antidepressants. It may also potentiate the effects of others [such as benzodiazepines] leading to drowsiness, poor judgment, or death.

For a comprehensive approach to the treatment of alcohol issues, see the alcohol treatment map on this site.

CAFFEINE

Caffeine is the stimulant of choice for many people. It occurs in a variety of forms, including coffee, tea, and other beverages. It-

- is commonly used to stay awake after sleep loss or to manage normal drowsiness.

- may give a false sense of alertness.

- can’t compensate for missed sleep.

- is included as a component of soft drinks, “enhanced” bottled water, tea, candy, toothpaste, most medications.

- may counter depressive feelings in some people.

- has a short term rebound that leads to continued use.

TOBACCO

- often used to deal with tension. It provides temporary relief but a longtime increase in tension.

- As with alcohol use, ask when the person smokes, how much, when he/she started smoking, etc.

MARIJUANA

- may be used to stimulate good feelings, to relax or sleep, or to control pain.

- may lead to anxiety about being discovered.

- may have side effects.

- possible rebound.

COCAINE

- the stimulating effect may be felt as an antidote to anxiety. Patient feels alert, strong, creative. Other people may experience an active user as racy or hyperactive.

- the aftereffect typically includes a depressive rebound.

- occasional users may use it to stay awake during the day that follows a sleepless night.

OTHER DRUGS

Need to be studied for their overall effects on the person and his/her experience and functioning.

Any use of illegal substances can lead to an overall increase in anxiety, because of-

- fear of being discovered and/or of legal consequences.

- association with others whose needs lead to increased tension, possibly through illegal activities.

References:

Preston, O’Neal and Talaga, 2002

Thomson Health Care: PDR Drug Guide for Mental Health Professionals