SECTIONS: 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 19 | 24

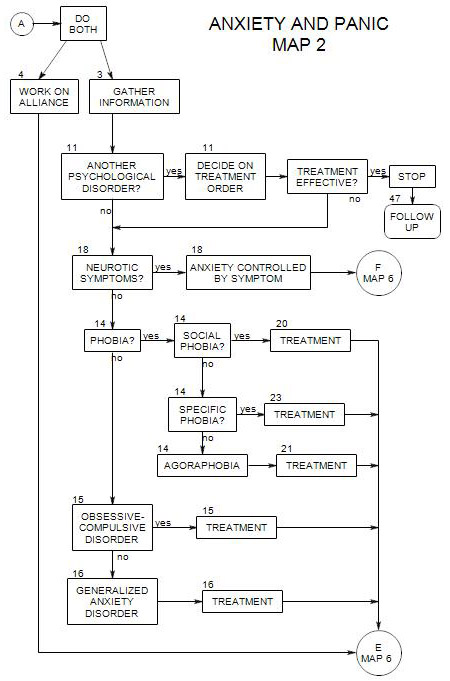

- Follows Section 14 on Map 2

A person with an obsessive-compulsive disorder is plagued by intrusive, thoughts, impulses or images that are recognized to be senseless but that at the same time cause him/her considerable discomfort. He/she may also engage in repetitive, ritualistic behaviors, the primary purpose of which is to relieve the disturbing thoughts and prevent stress and anxiety from increasing.

The obsessions often are about relationships with other people or the outside world, such as –

- cleanliness, with corresponding compulsions about cleaning or avoiding dirt or germs.

- safety, with corresponding compulsions to check – that the door is locked, that the stove is turned off, etc.

- hurting oneself or others, with rituals attempting to prevent or undo aggression.

- incompleteness or disorder, with compulsions to arrange objects, remove things, or repeat behaviors.

A person’s ritualistic compulsions may be behavioral [eg: hand washing] or mental [counting or praying]. People typically know that their compulsions are not rational, but they seem necessary to manage the obsessive thoughts. The compulsions must be repeated again and again, because the thoughts keep returning. There is typically no pleasure associated with the compulsion – only temporary relief.

There typically is a strong connection between a compulsive ritual and the thought that it attempts to neutralize. Fear of germs can lead to excessive handwashing; fear of explosion can cause a person to check the gas stove again and again, and so on.

The obsessions and corresponding compulsions are painful and intrusive. However, the compulsions are maintained because they provide temporary relief from the obsessions through taking action. At the same time, the obsessions may be reinforced by the fact that they are temporarily relieved by the compulsive actions.

Obsessive people also avoid situations that make them uncomfortable, much as phobic people do, and may arrange their lives so that their issues rarely arise. This can lead to an uneasy truce between experiencing the symptoms and avoiding the situations where they are triggered. Where avoidance isn’t possible, symptoms can interfere with work, social activities and personal relationships.

Some people have obsessions without associated compulsions. They are especially difficult to treat, because there is no behavior to manage, and no direct access to the person’s thoughts. Treatment can involve asking the person to think the dangerous thought but not the thought that manages it.

15a. Obsessive Personality

It is important to distinguish the diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder from that of obsessive-compulsive personality, which is ego-syntonic and not anxiety-driven, and for which the treatment is entirely different. People with obsessive personalities are rigidly moralistic, conscience-driven, fussy about details, perfectionistic and indecisive.

15b. Formal Diagnosis

300.3: Obsessive-compulsive disorder

301.4: Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder

15c. Comorbid Conditions

Because the disorder is constantly stressful, with massive anxiety the consequence for attempting to forego the associated compulsions, it can wear a person down, leading to dysthymia and a sense of hopelessness. If a person is very depressed, consider starting him/her on an SSRI [see below] immediately(Foa and Kozak, 1996, p. 163).

Panic attacks can happen any time that obsessive thoughts or compulsive rituals are thwarted. In this way, they reinforce the thoughts and behavior, because the person has proof that failure to continue with them leads to terrifying consequences.

Drug and alcohol abuse are very common with people suffering from obsessive compulsive disorder, possibly as an attempt to self-medicate – either to reduce the anxiety or to drive out the intrusive thoughts.

You should also be watchful for other disorders that are often comorbid with OCD: panic, phobias, tic disorders [including Tourette’s syndrome], autism and schizophrenia.

15d Beginning Treatment

An early step in any treatment is determining the full range of obsessive thoughts and situations that are avoided, and understanding their meanings for the person. The obsessive thoughts can then be placed in a hierarchy according to the amount of anxiety, discomfort or attention connected to each one.

At the same time, you need to explore all of the ritualistic ways that the patient uses to counter his/her obsessions, including both ritualistic behaviors and compulsive thoughts (Foa and Kozak, 1996, pp. 153-154).

15e Choice of Primary Treatment

The evidence is that the primary treatment must be behavioral, and that all other treatment forms, including cognitive and psychodynamic therapy, are mainly helpful as adjunctive work.

Exposure

This might be the treatment of choice for a person with mild symptoms, or a person who refuses medication.

The compulsions are extinguished through exposure and response prevention [ ERP: Section 27 ]. Depending on the nature of the obsessions, work can be either imaginative or in vivo. In either case, the person is encouraged to have the thought but prevented from engaging in the compulsive reaction to it.

If the obsession is triggered by external cues, in vivo exposure is usually recommended. If the cues are internal, imaginal exposure is recommended. (Foa and Kozak, 1996, pp. 155-56).

The amount of time spent in exposure without ritualistic responding should be substantial, in order for the treatment to be effective. Foa and Kozak use 2 hours per day, 5 days per week for two weeks. Others have recommended weekly sessions over several months. Over time, the link between cue and compulsive behavior is extinguished, reducing the power of the obsession as well. For a more complete description, see Foa and Kozak, 1996, pp. 139-171.

As noted in Section 27, however, when the task of treatment involves focusing a patient’s attention on a painful or anxiety-provoking thought, the patient has a strong motive to avoid the thought. It is difficult to remain focused. Because of this difficulty, some part of the work may involve assuring that the task is carried out. This can be done as in suggested in <Section 33.

Presumably, as the compulsions are extinguished, their ability to reinforce the corresponding obsessions diminishes also, reducing the power of the obsessions.

Substitution

Here the connection between the thought and corresponding compulsive behavior is extinguished as the person learns to perform a competing behavior instead. “Instead of going back to check the lock, take a deep breath.” This of course includes response prevention implicitly.

Saturation

In this case, the person is asked to focus on the obsessive thought in a flooding format [ Section 34 ], to the point that it loses its meaning. Treatment can include a visual or auditory presentation of the dangerous thought or situation, possibly repetitively, that the person attends to without reacting in the usual manner. This procedure also implicitly includes response prevention.

Other Procedures

Other techniques for anxiety reduction have generally been found to be unhelpful or unreliable as the primary form of treatment for OCD. They include meditation, thought stopping, aversion procedures, relaxation, imaginal flooding, paradoxical intention, cognitive therapy and psychodynamic therapy.

Medication

Here SSRI’s are the medications of choice, even if the person is not depressed. This is because serotonin regulation appears to be involved in obsessive thinking. (Hollander, Aronowitz and Klein, pp. 338-342) Using SSRI’s is effective in controlling obsessive thoughts in about 65% of cases, and consequently the compulsions and avoidances as well.

Treatment using antidepressant medication usually requires higher doses than for treatment of depression (Preston, O’Neal and Talaga, 2002, p.116 provide a table of typical doses), and may take longer to become effective – sometimes as long as three months or more. For this reason, it usually doesn’t pay to wait for the drug to work, and psychological treatment should begin immediately. However, the guidelines for treatment are the same (see Preston, O’Neal and Talaga, 2002, ch. 15). Some patients have difficulty tolerating the higher doses of antidepressants needed for treatment. (Beitman and Saveanu, 2005, p.422).

All SSRIs have side effects, which must be tolerated in order to continue taking them. However, because both primary effectiveness and side effects vary from patient to patient, drug treatment often involves some trial and error. Choice of medication is generally negotiated between patient and prescriber, based on reports of drug effectiveness, prescriber preferences, and the patient’s choices among typical side effects.

Typical side effects for SSRI’s include nausea, insomnia and loss of libido. Commonly, side effects are experienced before the primary effect, leading some people to discontinue before the medication is effective. Then they may be discouraged about medication effectiveness.

Commonly used medications include Prozac [fluoxetine], Luvox [fluvoxamine], Paxil [paroxetine] and Celexa [citalopram] and Zoloft [sertraline]. Some prescribers prefer Effexor [venlafaxine], which affects the regulation of both serotonin and norepinephrine.

A prescriber may try different doses of a chosen medication, and possibly augment the primary medication with another, like Risperdol [respiradone].

The general unpredictability of results is a second reason to begin psychological treatment immediately.

On termination of the medication the symptoms almost invariably return, typically within a few weeks, unless psychological treatment is working as well. [Foa and Kozak, 1996, p. 151; Preston, O’Neal and Talaga, 2002, p. 117] For that reason, it is generally recommended that ERP continue even if medication appears to be effective. This constitutes a third reason to begin ERP immediately – so the patient come to rely solely on the medication and then relapse.

15f Adjunctive Treatment [ Section 30 ]

COGNITIVE THERAPY can be helpful if the person suffers from

- obsessive doubts

- excessive feelings of responsibility

- excessive need to control others, situations, or his/her own thoughts

It can put the obsessive thoughts into a different perspective, as a way of reducing their power.

For example, a patient can be led to challenge the idea that he/she ought to be able to control his/her thoughts and eliminate any that are unacceptable.

PSYCHODYNAMIC THERAPY can be used to explore-

- other issues that are contributing to the person’s anxiety – and indirectly, to the power of the obsessions, including doubts, fears, and unacceptable sexual or aggressive impulses.

- consequences of obsessive behaviors in self-esteem and interpersonal relationships. This can bolster the person’s resolve to stay in treatment and work on related issues.

- childhood history, possibly of great responsibility or rigid rules. If so, then awareness that they were learned early and well can free a person to experiment with alternative thoughts and behaviors.

- other issues, such as early teaching that thoughts and actions are morally equivalent or that having a thought increases the probability that the thing will actually occur.

Support Groups can be helpful, if they are available.

Family and Friends may have complex relationships with the patient and his/her symptoms, including-

- frustration and resentment at having to deal with the consequences of the symptoms. This can lead to anger at the patient and critical judgments of him/her.

- impatience with the treatment, wanting it to work immediately.

- support for the treatment and the patient’s attempts to change.

- resistance to modifying their own adaptations to the patient, which may in fact be enabling the compulsive behaviors.

There may be some value in including at least some of the patient’s family and friends in the treatment plan, either directly or as enlisted by the patient. Their reactions to the patient can be examined in individual treatment regarding their impact on the patient’s symptoms and attempts to overcome the symptoms.

15g. Treatment Effectiveness

When the disorder is resistant to treatment, it may be due to failure to treat comorbid conditions [personality disorder, social phobia, tics, or neurological disorders] [Hollander, Aronowitz and Klein, 340], and a re-evaluation may be in order. It may also be that there are unconscious roots to the person’s obsessions, and further psychodynamic exploration [ Section 28 ] can be useful.

15h. Follow-up

Return of symptoms is common, and follow-up can be helpful to the person. It is a good idea to schedule follow-up sessions as a part of termination.