SECTIONS: 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 19 | 24

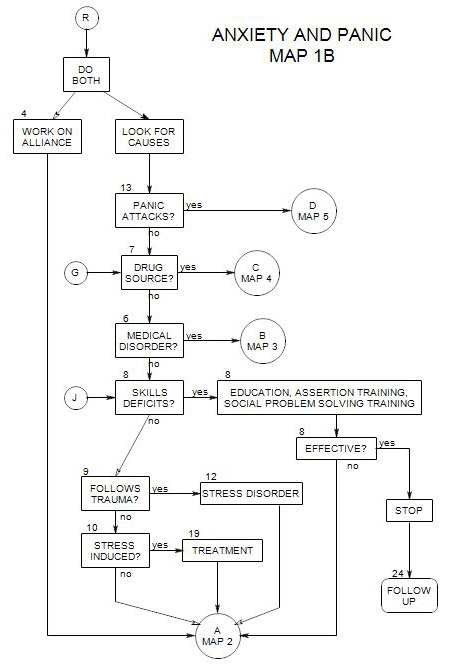

- This section continues the process started in Section 2. It also coordinates with Section 4 on treatment alliance.

An anxious or phobic person is typically doing everything he/she can in order not to be anxious or fearful, and failing. You need to know, not only what the source or sources of his/her fear or anxiety are, but also what he/she is doing to deal with those feelings, and why it isn’t successful.

This is an ongoing process. Try to ask enough up-front in order to make a first plan for treatment, and go from there. But for many reasons, relevant information may only come to your attention later in the treatment process, because-

- you are better-oriented relative to the patient and his/her issues.

- the patient may be more attuned to relevant symptoms and more likely to report them.

- your questions can be more specific.

- repressed experiences and thoughts may emerge.

So, on the one hand, whatever initial diagnostic impressions you may have will determine to some extent the direction of treatment and the kinds of information you look for. At the same time, it is important to be alert to disconfirming information, so you don’t continue in an unproductive direction.

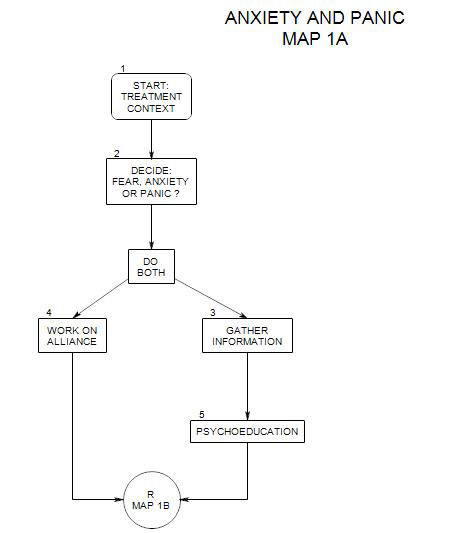

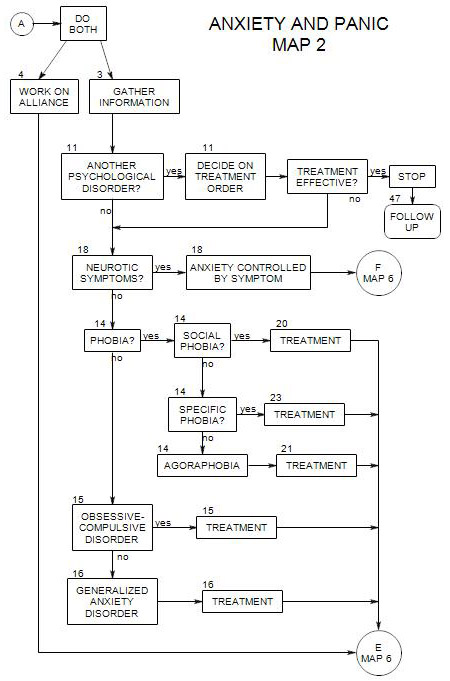

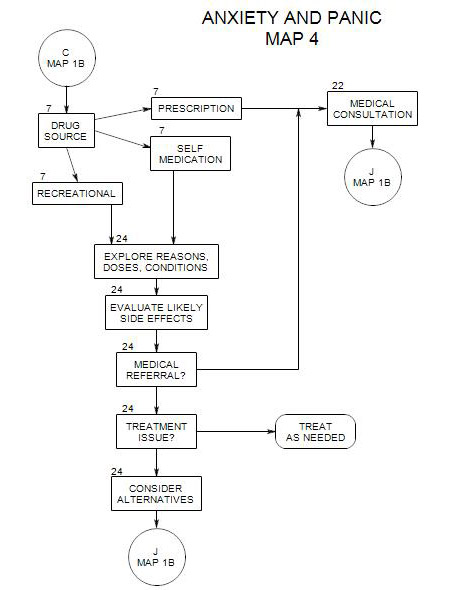

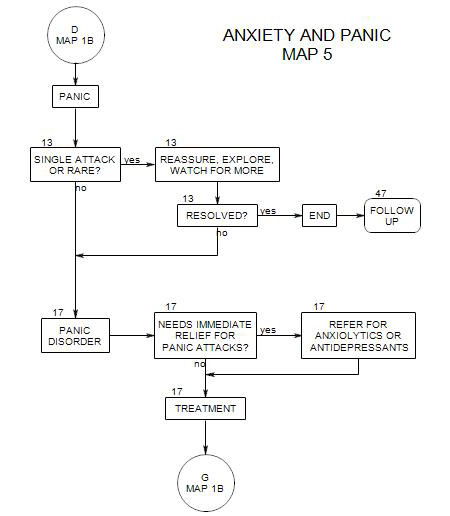

The maps are organized first to look for sources of anxiety [medical disorders, drug effects, internal conflicts] and then to sort people out according to some common diagnoses.

Key elements to explore include- [Wolfe, 2005: p.272]

- the nature of the patient’s symptoms.

- the intensity of the emotional reaction.

- the extent of its interference with patient’s life.

- the underlying catastrophic events and conflicts [if any] and the self wounds they reflect.

- other physical and psychological problems.

- how the person copes with anxiety.

- what maintains the fear or anxiety in the patient’s life.

- the degree of connection between the auxiliary problems and the anxiety symptoms.

- the extent to which the patient’s fears are chronic and constant or episodic and situation-related.

If anxiety is chronic, it will be helpful to ask…

- when it began, and what was happening around that time.

- if it increased, then what was happening around that time that might have led to the increase.

- if it decreases at times, then what provides relief or may lead to the decrease.

If anxiety is episodic, it can be helpful to ask-

- when it is more frequent.

- what may precipitate bouts of anxiety.

- what is helpful in dealing with it.

Many people are aware of their anxiety and have conscious strategies for reducing it or managing it, including-

- drinking alcohol.

- cigarette smoking.

- smoking marijuana.

- taking prescription medications.

- pacing.

- meditating

- using relaxation techniques

- listening to music

- watching television

- walking outdoors.

Ask what the patient does to manage anxiety, and find out the details.

Anxious people often engage in strategies designed to keep the underlying source of the anxiety hidden from self and others [Wolfe, 2005, pp. 265-267]. Strategies include cogitation, avoidance, and negative cycles of interpersonal behavior.

Cogitation occurs when a person thinks obsessively about the implications of being anxious. Cogitating typically increases the perceived level of anxiety.

Avoidance occurs in a variety of ways, including-

- thinking about something else.

- doing something to distract oneself.

- changing the conversation

- leaving the scene

Negative interpersonal behavior includes clinging, demanding help, or blaming someone else for perceived problems or disasters.

Questions to Ask

Any attempt to get at the person’s fears can run into a variety of obstacles. The person may be afraid to admit to having some fears, lest you judge him/her; or he/she may fear that talking about them will precipitate an anxiety attack.

You may need to begin with reassurances – your awareness that the questions may be anxiety producing, but that they are necessary in order to examine the person’s issues. You can also allow the person to defer answering any question that produces too much anxiety.

What does the person fear?

- Specific objects or people

- Situations with other people

- General situations [e.g.: going out of the house or to the city]

- Vague sources

This is a good time to begin making a list of things that the person fears: people, situations, animals, times of day, expectations, etc. Have two copies: one that the person takes away and modifies as time passes. You keep the second list in his/her file, refer to it in preparation for sessions, and modify it in response to new information or changes in the patient.

What are the person’s symptoms when fearful? Symptoms could include-

- avoiding the situation or person.

- waking in a panic.

- ruminating.

- physiological reactions, such as shaking, having difficulty breathing, feeling cold, sweating, etc. Having to urinate.

- laughing too much or talking excessively.

- withdrawing.

Defenses and Reactions: How does the person defend against experiencing the fear, or cope with it if it is felt? How effective are the person’s defenses?

Complications: There may also be a second level: does the person worry about being afraid and its consequences?

Also, we want to consider that there might be a psychotic part to the person’s fears – that the fear is so great that reality is compromised, or that the fear is based on a severe distortion of reality. We often say that a phobia is unrealistic – but the question can become: just how unrealistic?