SECTIONS: 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 19 | 24

36. ERICKSONIAN IMAGINAL DESENSITIZATION

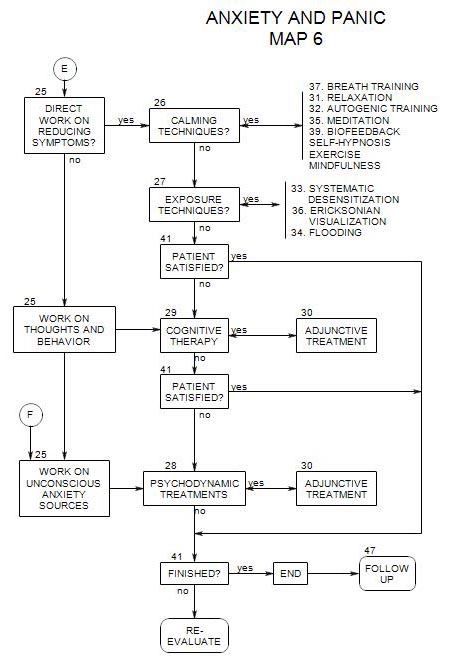

- This follows from Section 27, on Map 6

This is a variation of imaginal desensitization that is less formal and less structured than systematic desensitization and less traumatic to patients than flooding.

Technique

One way of going the process of overcoming a particular fear, such as flying in an airplane, is outlined by Wilson [1993, pp. 270-277]. It uses several techniques adapted from the work of Milton Erickson

- Go on to a fantasy of just having overcome the phobia, and follow that through- the immediate feelings and thoughts of success.

- Continue with a silent fantasy of successfully completing the feared confrontation or activity – but with limited time to go through it, giving the person inadequate time to be properly anxious.

- Begin with an image of the patient already having been successful at overcoming his/her fear. Work through the feelings of having successfully finished with it.

- Suggest that the person will feel supported by thoughts of success at overcoming his/her fears

- Suggest that the person continue to practice the success imagery on a daily basis, and that the imagery will give him/her confidence to begin dealing with the phobia directly.

Wilson doesn’t provide details on the transition from desensitization to dealing with the feared situation or object in the person’s life. Presumably, a transition to any of the other four forms of exposure could be made after this technique is used for the initial work.

36a. Breath Training

Carmin and Pollard (1996, p. 60) recommend breathing training as an anxiety management skill that can more easily be taught to patients than relaxation training, and is more effective for dealing with acute stress.

Their directions to a patient are to-

- slow his/her rate of respiration as much as comfortably possible, and to focus on keeping the rate slow,

- breathe in and out through the nose [to avoid hyperventilation], and

- breathe deeply – into the diaphragm rather than the upper chest.

The overall goal is to reduce ventilation – to reduce oxygen intake and reduce carbon dioxide in the blood. At the same time, the patient may experience greater control over the breathing process, which is reassuring.

Carmin and Pollard recommend that patients practice breathing this way regularly, especially in situations that might be anxiety provoking.

36b. Hyperventilation exercise

One goal of treatment is to give the patient the sense of being in charge of him/herself. Some of this can be attained by the realization that breathing is under at least partial voluntary control.

In addition, it is important to break the connection between the experience of lack of control and thoughts of doom and inevitability.

Because a person’s breathing may have an impact either on the initiation or maintenance of anxiety or panic symptoms, Schneider and Ruhmland (1997, pp.22-23, 27] give a brief outline of a hyperventilation exercise and symptom checklist.

The primary intervention is to have the person breathe through the mouth and into the upper chest at a rate of one breath a second for two minutes, and note the effect on his/her anxiety level [it increases]. Having a person hyperventilate in the therapy session can help identify physical symptoms, distinguish them from emotional reactions, and begin to work on techniques for self-regulation.