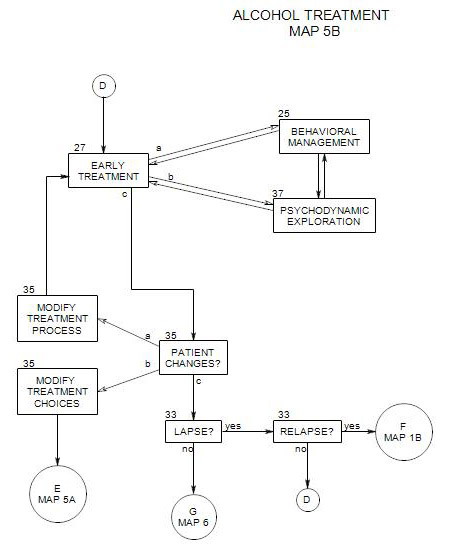

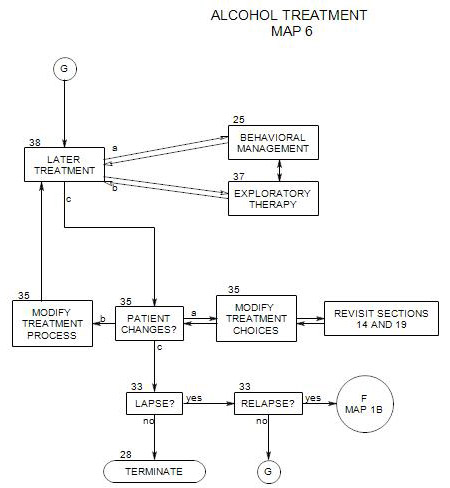

27. EARLY ONGOING TREATMENT

- This section follows Section 19 on Map 4 and provides an overview of early treatment with alcoholic patients. It coordinates with Section 25 [Behavioral Management] and Section 37 [Psychodynamic Exploration]. It assumes that a patient is in the action stage [ Section 40 ], although there are applications that can be helpful in contemplation and preparation. People in earlier stages are more likely to benefit from motivational interviewing [ Section 24 ] or supportive psychodynamic therapy [ Section 37 ].

This section is part of a common path for patients with varied current and previous relationships with alcohol and a wide range of prior treatment experiences. It was written from the perspective of individual psychotherapy as the primary treatment mode and others as adjunctive.

Treatment of alcoholic patients has two interrelated functions: [1] preventing relapse; and [2] working on other intrapsychic and interpersonal issues that can lead to a richer and more fulfilling life. These go together, especially as drinking is often a defensive reaction to life difficulties and at the same time can be a source of difficulties. Typically, and depending on the patient’s background and degree of abuse or dependency, early treatment is focused more on dealing with the urge to use alcohol, and later treatment is focused more on dealing with aspects of the patient’s life that were neglected or mishandled in the past.

Many of the issues and procedures for a person who is trying to get sober are similar to the issues and procedures for a person who is trying to stay sober. In this treatment, they will be handled in parallel or interchangeably where appropriate.

There are many factors to consider in the ongoing process of tailoring the treatment to the patient’s needs. Some of those issues will be considered in the present section. The first three subsections [a through c] deal with treatment process and the remaining [d through j] with more specific treatment topics:

- Symptoms and issues of early treatment

- Engaging the patient

- Behavioral management vs. psychodynamic exploration

——————————————————————-

- Identifying and managing cravings and triggers

- Other psychological issues or disorders

- Abstinence and other patient goals

- Finding alternatives to drinking

- Examining the consequences of drinking

- Risk of relapse

- Managing the recovery process

It is not clear in the abstract in what order these should be addressed. You should focus on the issues that seem relevant for a given patient, and within that context, keep the entire list in mind and see what opportunities arise in session.

27a. Symptoms and Issues of Early Treatment

Early in treatment of a patient in the action stage, a major focus must be on the patient’s drinking, and the treatment typically has to be practical and alcohol-focused, with emphasis on external management, support and control. Patients not yet in the action stage need motivational interviewing [ Section 24 ] or supportive therapy [ Section 37 ] as preparation for the work described here.

For many patients, management should be structured, because reliance on alcohol leads to confusion and disorganization. Treatment can include –

- identifying people, places and situations that could lead to relapse, and making concrete plans to avoid them whenever possible.

- developing specific plans for coping with people, places and situations that can’t be avoided.

- making lists of people to contact and hotlines to call if cravings become difficult to avoid or manage.

- providing details about the therapist’s availability – times to call, possible additional session times, and so on.

If the person was physiologically dependent, then many of the symptoms of alcohol and detoxification – difficulty sleeping, persistent cravings for alcohol, difficulty experiencing pleasure – may persist for weeks or months. New symptoms may also appear, as the patient’s preferred medication continues to be unavailable. These symptoms may interfere with daily living and serve as triggers for relapse.

A major issue for patients early in sobriety is time management. The availability of time that is un-accounted-for can open up opportunities for drinking – opportunities that the person may have difficulty resisting at this point. It may be helpful to have the patient work out a written, detailed schedule – hour-by hour – for each day. Such a schedule could include –

- work or school;

- meals, sleep, and time with family and friends;

- therapy sessions;

- self-help meetings;

- travel time;

- alcohol monitoring, if mandated or otherwise desirable; and

- other regular, time-binding activities.

When a patient is disorganized, it may fall on the therapist to be more active and controlling, both within sessions and outside them. The work can include regular contacts with others, more active control of sessions, help with the practical organization of the patient’s day, and so on, depending on patient needs.

Early on, a patient may need frequent sessions to stay in contact, to bolster his/her resolve, to examine reactions, or just to stay alive. It can be critical to have two or three sessions a week with a patient in crisis, and – rarely – daily sessions may be necessary. Frequency of sessions may be reduced over time, as pressures to drink abate and are managed in other ways.

Early treatment tasks include –

- getting the patient to come.

- getting the patient to talk and be engaged in the treatment process.

- dealing with the patient’s alcohol issues.

- dealing with the patient’s other psychological issues.

It may also be necessary to monitor treatment adherence and progress early on in treatment, through use of routine tests, contact with adjunctive care providers, or sessions with other family members. As the patient becomes more secure in his/her sobriety, monitoring becomes less important.

27b. Engaging the Patient

The work requires a background of patient trust and willingness to be open about both alcohol and other psychological issues. This trust must be established early in treatment and actively maintained. The patient must be encouraged to believe that the therapist is totally trustworthy, and that anything can be said and handled, whether it is the patient’s feelings, attitudes or behavior. This is done in many ways, through therapist caring and honesty, clarity of procedures and expectations, and security of treatment process, setting and record keeping. Motivational interviewing techniques [ Section 24 ] can be helpful with many patients.

Full openness and disclosure run contrary to an alcoholic’s typical way of operating and experience of others. It may also require that the therapy become more of a collaborative sharing than is typical in behavioral approaches and more open than is typical in psychodynamic work. In terms of Freud’s structural model, we want to ally ourselves with the patient’s ego and help strengthen its ability to manage the patient’s superego, id and external reality.

The more effective approach is akin to supportive psychotherapy with some exploration of unconscious material as it becomes relevant [see Section 37 ]. Early on, defenses are supported – at least some defenses – exploration of the unconscious is kept to a minimum, and the work is used to help the person gain behavioral self-control. Treatment should make sense to the patient, the therapist’s questions should be meaningful, and the patient should feel more aware and in charge as a consequence of the work. As treatment progresses and behavioral self-management becomes more reliable and automatic, more psychodynamic exploration can be introduced.

27c. Behavioral Management versus Psychodynamic Exploration.

One way of looking at the various aspects of treatment is to divide them into approaches that focus on the management of symptoms, and approaches that focus on a patient’s increased self-awareness. In this discussion, the former will be called Behavioral Management and the latter Psychodynamic Exploration. Management issues are discussed in Section 25; psychodynamic approaches are discussed in Section 37.

There has been much controversy about which to use in treating patients. An optimally effective treatment plan should take advantage of the strengths of both approaches. Here, the argument will be that –

- both approaches have their places.

- they are used under different circumstances and for different purposes.

- they complement each other at times.

Behavioral Management focuses on ways to help the person do what is needed, especially with respect to alcohol. This is consistent with the standard practice of alcohol treatment, which has focused on management of the person’s thoughts, behavior, relationships, and environment. A central premise is that an alcoholic’s drinking must be controlled, first and foremost. This is the position of Alcoholics Anonymous and most drug and alcohol counselors. An alcoholic is out of control, and the idea that he/she can control him/herself is misleading and destructive.

Behavioral control may involve thinking and planning by both patient and therapist. An alcoholic needs to focus on controlling his/her own behavior, using as much outside support as necessary: meetings, a sponsor that one talks to regularly, avoidance of temptation, rituals to maintain sobriety, and so on. The therapist typically takes charge of sessions, chooses behavioral interventions and forms of adjunctive care, provides ways to monitor treatment adherence and progress, and evaluates treatment effectiveness.

Behavioral management has many advantages. When it is effective, it gives immediate results, and alcoholics in recovery have need to take control of their drinking behavior immediately. Learning to manage one’s behavior can also lead to increased understanding, as the person watches his/her own reactions and tries to make sense of them.

On the negative side, internal changes may be slow to happen when behavioral management is the primary way of dealing with alcohol misuse, and the management strategies may have to continue for a long time. According to Alcoholics Anonymous, the need for long-term management is part of the nature of addiction. It may also be partly a consequence of treatment techniques that rely more on behavioral control than increased awareness.

Psychodynamic Exploration focuses on a person’s thinking and emotions, understanding the meanings of a person’s behavior and thoughts, and using increased insight as a lever for change. Its goals include strengthening inner resources and putting the higher cognitive centers in control of the person. Assumptions are questioned, habits are challenged, ineffective defenses are exposed and more effective defenses strengthened. The person’s unconscious determiners are made conscious in order to gain control of aspects of thinking that have been operating out of control. Unconscious conflict is brought to conscious awareness and examined. Distortions in thinking are examined and resolved. Many think that this approach will be more efficient and effective in the long run than behavioral management for controlling unwanted thoughts or behaviors, including alcohol misuse.

It has many advantages as a treatment form. It is relatively flexible, and it is easy for therapist and patient to move from one issue to another as a function of patient need or therapist judgment of relevance or effectiveness. Psychotherapy is never just about drinking, and psychodynamic treatment can take up any related issue as it develops. In fact, many patients don’t think of their alcohol use as a problem and will want to spend more time on other issues and the broader context of their lives. Psychodynamic exploration enriches the patient’s self-awareness, increasing patient motivation while providing a wide range of relevant material to explore. When symptoms are being maintained by unconscious conflict, bringing the conflict into conscious awareness and resolving it can help to undermine the symptom.

On the other hand, the results of psychodynamic exploration are generally not immediate, and a patient’s drinking issue is very immediate. Understanding doesn’t necessarily lead to action, and early in recovery, the focus is on action. To the extent that changing behavior is the primary focus at this time, psychodynamic exploration is an adjunctive approach.

In recent years, Cognitive Therapy has developed as a body of theory and techniques that has influenced all aspects of treatment. However, in the present work, much of it has been incorporated into the other two approaches for simplicity of presentation.

AND SEVERITY OF THE PATIENT’S DRINKING PROBLEM

There are many ways that severity of the patient’s dependence on alcohol affects treatment choices. One classification system [Leeds and Morgenstern, pp 79-80] posit three levels of drinking.

- Normal use is mainly determined by social and cultural factors. A person drinks at parties, dinners, and other events where others commonly drink. He/she drinks about as much as most other people, possibly less. He/she doesn’t use drinking in any other way and doesn’t think about it much on other occasions. We are not concerned these people here.

- Some people come to depend on drinking to avoid responsibilities, conflicts, or painful emotions. For them, alcohol has become a defense, and it isn’t working very well. They are candidates for psychodynamic exploration, to determine the sources of their conflicts and find more effective defenses. Section 37 focuses on this approach.

- For some, drinking increases to the point that they are driven by the need for alcohol, by thoughts of drinking, by learned and mostly automatic reactions that drive them to drink. For them, psychodynamic understanding isn’t enough and may simply miss the point. They need behavioral control first and foremost. Once the person’s drinking behavior is under control, then psychodynamic work can – possibly – address the underlying emotional or conflicting sources of the person’s need to drink. Start with Section 25 to work with these patients.

AND TIME IN SOBRIETY

An optimally effective treatment plan will take advantage of the strengths of both behavioral and psychodynamic approaches.

Early in treatment, the most serious issue is usually the patient’s drinking. A person who continues to drink or who relapses is unable to make much progress with psychodynamic issues; so for anything to happen, the person’s drinking has to be brought under control and kept under control.

There is some consensus that once an addictive disorder has achieved sufficient severity and chronicity, behavioral, cognitive, environmental and biological issues are essentially responsible for maintaining the disorder [Keller, pages 88-90]. Regardless of the patient’s type of misuse, he or she is best assumed to be – or to have been – at level 3 in the severity typology presented above. Therefore, early in treatment, whether the patient is newly sober or still drinking, the primary treatment modality must be behavioral management [ Section 25 ] in order for the treatment to be effective. To attempt to manage the person’s drinking disorder with increased awareness through psychodynamic treatment is likely to fail because it doesn’t address the salient determiners of the behavior.

Psychodynamic exploration is still important at this time, for several reasons.

- Therapist attention to defenses and unconscious conflicts can be important from the start, as an aid to behavioral management. When defenses and unconscious conflicts pose a threat to treatment, expressive-exploratory techniques are used.

- An understanding of a patient’s defenses, conflicts and personality traits can ease difficulties in learning behavioral skills, as well as how the behavioral task is approached and performed.

- An alcoholic person has psychological issues to deal with, and a psychodynamic approach can be helpful with those issues.

- Later, as treatment of the other issues gains in importance, it is good to have an established pattern of working on them psychodynamically.

As time passes and the patient’s drinking behavior comes more under control, a greater portion of treatment time and effort can be directed toward understanding the patient’s reasons for drinking and dealing with other psychological issues.

27d. Identifying and Managing Cravings and Triggers

A craving is a strong urge to drink, which may occur regularly in certain situations or appear seemingly “out of the blue”. It may be an insistence or an obsessive preoccupation. It may be experienced as increasing while the person is in the presence of the situation or thought, often to the point that there is no apparent choice about giving in to it. If the patient can’t drink, symptoms may come to feel similar to having a panic attack.

Cravings are a normal consequence of alcohol dependence, but they don’t lead inevitably to “picking up”. A major focus of early sobriety is the behavioral management of cravings [ Section 37 ]. They are strongest and most frequent when a person is newly sober and diminish over time.

Urges to drink can be stimulated by a wide range of internal and external cues: stimuli that have come to be associated with drinking to the point that they can almost seem to cause the person to drink. These cues are called triggers. A wide range of experiences, thoughts and emotions can serve as triggers for a person, including other people, thoughts, places, memories, times of day, emotions, occasions, etc. A major task of early treatment is identifying, keeping track of, and managing the issues that prompt an urge to drink.

Common triggers may include –

- strong negative emotions, such as frustration, anger, confusion, shame, guilt, depression or anxiety – especially emotions that the person may have managed in the past by drinking.

- physical stresses, such as chronic pain, fatigue, or difficulty falling asleep.

- positive situations, that “call for a celebration,” or that have been associated with drinking in the past. This could include business lunches, the end of a day or week, a particular restaurant, or a special friend who drinks.

- physical situations that the person has found tempting in the past, such as driving past a liquor store or being home alone with nothing to do.

- social situations, such as parties or sporting events, where friends are drinking.

- general availability of alcohol, especially at times and places where there are no natural external controls; for example, being home alone, with an open bottle of something tempting.

- recurrent themes, with their own triggering potential or pressure of habit. Examples might include arriving home after work, the end of the work week, or Monday night poker with “the guys”..

There also may be conflicts and issues in everyday life that lead the patient to feel the need for alcohol. Especially important are issues that have led to drinking in the past. In such cases, the patient’s established habit of drinking in response to those issues leads to expectations of dealing with them by drinking more or less automatically in the future.

A patient can be encouraged to notice and keep track of triggers. A list may be helpful, and the triggers may be examined and cataloged according to similarities. If a particular trigger is situation-related, then management solutions [ Section 25 ] may be effective. If the stimulus is a mood or conflict, then greater awareness of the psychological issues may be needed, and both management and exploratory techniques [ Section 37 ], may be helpful. Early on in recovery, the emphasis is typically on management, and exploration is used primarily to identify possible difficulties in self control. As treatment progresses and the patient is able both to maintain sobriety and to self-observe more effectively, exploration can provide material useful for increasing self control through increased understanding.

ANTECEDENTS OF THE URGE TO DRINK

If you want to know why a person feels a need to drink, the details of his/her drinking behavior are very important. The actual triggers may be out of awareness and different from what he/she has conceptualized. However, even if the triggers are subtle, you may be able to infer them from these details.

You can ask questions like the following:

- When does the patient feel the urge to drink? [times, occasions, settings, circumstances] How frequent do the urges come? Does an urge always lead to “picking up”?

- With whom does the person usually drink? Social pressure can be a potent factor.

- What leads to wanting to drink?

- What is the patient’s drink of choice? What else will he/she commonly drink?

Questions like these, directed at the details of the person’s drinking behavior and the circumstances or habits connected to drinking, help you work out a plan that can help reduce or stop drinking. They also help you make plans together that will help prevent relapse, once the patient is sober.

INTERNAL CONTEXT OF URGE TO DRINK

People may drink for many reasons having to do with management of moods, emotions or physiological responses. They drink to relieve boredom, anxiety, or anger, or to temper or stimulate excitement. They drink to reminisce, to re-live experiences, to stop ruminating, or to relax.

Some people may consciously use alcohol to self-medicate for a physical or psychological problem. It may be their primary treatment for a painful condition, or a supplement to opiates when their prescriptions run out.

On the other hand, a person may not realize that there is a connection between his/her alcohol use and some issue or symptom. In that case, you might need to lead the discussion a bit, by looking for relationships between drinking and other issues the patient has mentioned.

- Drinking could be used to control physical pain or to get to sleep at night.

- On the psychological side, it could be used to manage anxiety [especially social anxiety], depression, or anger.

- It could be used to mask side effects of bipolar disorder or attention deficit disorder, or any of a range of other problems.

LARGER CONTEXT OF DRINKING

It can be helpful to know the outside pressures on a person that provide a context for drinking. Specifying the pressures can sometimes lead a person toward finding ways to cope with them and not drink; or it may provide a starting point for therapeutic interventions that can reduce the pressures. Consider the patient’s partner, family, friends, work, subculture and neighborhood as possible current sources of influence. Family history can provide models and expectations about drinking, the context of drinking, the social mores around drinking, and so on. If pressures can be identified that lead to excessive drinking, then you and the patient can decide whether to deal with each pressure behaviorally, interpersonally, or through self exploration.

DRINKING HISTORY

A person’s drinking history is a rich source of information that can be useful in both achieving and maintaining sobriety. Knowing the person’s recent history helps with behavioral management by suggesting current pressures and situations that support the person’s drinking and may be open to control through behavioral management. Knowing more distant history may help in reducing the person’s vulnerability because of underlying psychological pressures that have not been resolved, defenses that need to be been modified to be more effective, expectations that need to be changed, and so on. Some aspects of drinking history include –

- the family drinking history.

- the patient’s first drink.

- drinking in adolescence and young adulthood.

- previous attempts at abstinence – when, why, and how long they lasted. Reasons the patient relapsed.

- recent changes in the person’s drinking patterns or quantity.

A family drinking history can give information about the person’s expectations of when drinking is approved and disapproved. It provides models for how to drink, how much and what to drink. A number of avenues can be followed, if they seem relevant.

- Was drinking allowed in the patient’s childhood family? Was it encouraged? If so, by whom and how?

- Was drinking part of family events? If so, which ones? Before dinner? Weekly? Holidays? How were the events affected by drinking – did family members get more relaxed, more belligerent?

- What forms of alcohol were allowed and encouraged? Beer? Martinis? Is there a connection to the patient’s current preferences, and if so, what is it?

- Who drank? All adults? Some adolescents or children? This may bear on the person’s idea of having a right to drink

- Who drank, specifically? Uncle Einar? Mom? Cousin Tommie? What did they do when they were drinking? What did other family members think and say about them? Who approved and who disapproved? Perhaps that person serves as a model for drinking even now, or leads to feelings of self loathing when the patient drinks too much.

The first drink the person had is often important, especially to someone who later becomes addicted. The details of the first drink can give information about the person’s experience of drinking – expectations and the kinds of pressures responded to.

- When and where did it occur? Why then, and not some other time?

- Who was present, and what was the emotional context?

- How was drinking presented to the person?

- Did the experience meet expectations? Was it positive or negative?

- as this a one-time experience, or did the patient continue to drink in that same way or another way?

The person’s drinking in adolescence and young adulthood can set the stage for later drinking behavior, as he/she tries to hold on to that age or get away from it. The person’s reactions to context and peer pressures may be inferable from his/her recollections and associations.

Previous attempts at abstinence can give information about what worked and what didn’t – and possibly, why they were or weren’t effective. You may need to look at past failures in order to find the resources to continue trying. Often people believe that they have tried everything and that they are beyond help. A full understanding of previous failures can be helpful here, along with a detailed exploration of previous relapses. [“No, really: what specifically got in the way of your succeeding that time?”]

Recent changes in the person’s drinking patterns and habits give information about pressures on him/her, as well as his/her ability to modify drinking to cope with them. Long-term treatment will have to address those pressures, as well as the person’s ease in falling back onto alcohol to deal with them. Behaviorally, this means reducing the pressures through avoidance, new skills or alternative actions. Psychodynamically, it means dealing with the person’s perception of pressure and internal reactions to it.

The place of drinking in the person’s current relationships can be important to understand, as a way of looking for both behavioral changes that make drinking less likely and psychodynamic exploration that leads to other sources of satisfaction in those relationships. A primary relationship that is based on drinking together can be resistant to change in the drinking pattern of either partner.

How alcohol has affected the patient’s mood, attitudes and emotions can be informative.

For example, if a woman says that she has gotten drunk to control her anxiety, the follow-up might be to ask when that happened, to look for details about the anxiety and the situation. This could lead to different treatment solutions: [1] to help her find ways to avoid similar issues or situations in the future; [2] for her to learn alternative techniques for dealing with anxiety under similar circumstances in the future [e.g.: assertion training, if that is relevant to her issues]; or [3] to explore the reasons that the situation led to anxiety and deal with the psychological connection between the two.

In each case, the details are what matter. If the patient drank to have a good time, it might be interesting to ask why alcohol was needed. To relax? To feel comfortable with other people? To fit in when others were drinking? Whatever, the answer, it can lead to new options for the person, such as [1] avoiding the situation, [2] finding an alternative way to have a good time, [3] breaking the association between the situation and the feeling or [4] understanding his/her underlying motives and conflicts, and not needing to drink in order to manage them.

EXPECTATIONS AND CONSEQUENCES

Following are some possible questions related to the results or consequences of drinking. Perhaps the consequences are intended, perhaps not.

- People who drink, drink for a reason. What are the positive effects of drinking for you? What were your best and worst drinking experiences?

- Imagine yourself in a situation where you are about to have a drink. What is it? What are you doing? What are you thinking?

- What are/were hangovers like? [This can be a test of honesty: a patient who denies having hangovers is lying – unless he/she doesn’t recognize them because of other issues.] [The details of the consequences help you find out how much the person really drinks, as well as training the person to watch for the symptoms.]

- Have you ever experienced any signs of withdrawal [shakes, tremors] after going without drinking for a day or two?

- Have you had difficulty remembering the things you said or did while you were drinking? [Note that a blackout is a loss of memory due to drinking, and is not the same as passing out. It’s better not to use the word directly, because of the common misunderstanding.]

- Have there been any legal complications because of your drinking? What about other ways in which your life has been complicated? Have there been any interpersonal or financial consequences of your drinking? Have you ever engaged in sexual acting-out when drinking? Have you gotten into fights? Are you aware of any long-term consequences of your drinking?

- Has your drinking had any impact on your family or work?

- What have been the reactions of others [family, co-workers, friends, or boss] to your drinking?

27e. Other Psychological Disorders

People with serious alcohol misuse are likely to have other psychological issues as well, issues that may have precipitated their alcohol problems, that may have developed as a consequence of their alcohol misuse, or that may be more or less independent of it.

In addition, many alcoholics also use other psychoactive substances, including marijuana, cocaine, heroin or opiate painkillers. For these people, diagnosis and treatment are typically more complicated and difficult.

About forty percent of alcoholic patients have some form of depressive symptoms – some as a direct result of having alcohol in their systems, some in reaction to their awareness of being dependent on alcohol, some in reaction to their own behavior when drunk. Some drink to “numb-out”, as a way of coping with chronic depression.

Many people drink to cope with other moods – to temper their anxiety or anger, to stop ruminating, or to go to sleep. People with chronic pain often attempt to manage it with prescription medications and a variety of other physical and medical treatments; and when the other procedures or medications fail to control it completely, some supplement with alcohol or street drugs.

Alcohol is used by many people in attempts to cope with a wide variety of disorders: attention deficit; bipolar disorder; social anxiety, and so on. Heavy alcohol consumption can also lead to a range of other issues, including low self esteem, resentment, and guilt [Wallace, pp. 17-18].

It is often unclear as to how to proceed: should one focus only on the patient’s alcohol issues, only on other psychological symptoms, or both? A comprehensive approach might attempt to deal with all the patient’s issues together in an inpatient setting; but this may not be possible for many reasons. An outpatient treatment plan is typically limited by financial and/or time resources, and choices have to be made.

Treatment choices may be complicated by this diagnostic confusion in a variety of ways:

- A combination of a psychological problem and a drinking problem may lead to greater risks for the patient than either alone. Drinking can lead to greater confusion in a confused person, greater depression in a depressed person, and so on. These increments can put the person in increased danger.

- Psychotherapy for a psychological condition that is the consequence of drinking may miss the root of the problem and lead to wasted effort and discouragement, especially if the person continues to drink.

- If the psychotherapy is ineffective, the therapist can become discouraged about the patient’s apparent unwillingness to put in the effort to resolve the psychological issues.

- A psychological problem can lead to an increased pressure to relapse.

- Drinking may serve as a partial solution to a psychological issue, making the person less willing to invest effort in either sobriety or psychotherapy.

Sometimes a patient who uses alcohol to manage another symptom will come to realize that the alcohol itself can lead to dangerous consequences, in part by talking about it in therapy. That realization can become an incentive to stop drinking and work on other ways to manage the psychological symptom.

For example, a woman who was anxious about social events drank too much wine at a party and later found herself on a boat in the harbor with two men she had just met. The evening passed without incident, but on reflection she realized that she had placed herself at risk. For a while, she needed to go to parties with a friend or avoid them entirely because of the temptation to drink and put herself at risk [the behavioral management part] while she examined her social anxiety and her urge to drink to control it [the psychodynamic part].

Too little focus on a person’s alcohol issues can undermine treatment, in part by leaving unresolved a major contributor to other psychological issues. Too great a focus on alcohol can leave other issues unresolved and possibly unresolvable. If the person is using alcohol to manage other psychological issues, resolution of those issues may be an important first step, both because they matter to the patient and because treating them directly may partly undermine the patient’s need to drink.

SORTING OUT THE ISSUES

You cannot predict what other disorder or symptom an alcoholic patient may be suffering from, based on his/her alcohol use. You often can’t determine what it might be until the person has been sober for an extended period of time.

You may in some cases simply ask the patient about other psychological diagnoses he/she may have been given in the past, and the patient’s report can be helpful. However, previous diagnoses depend on the diagnostician and the conditions under which the diagnosis was made, and assume that the patient was accurately informed and remembers accurately. One way to guess whether the patient’s other psychological issues are a consequence of drinking is to try to find out the time of origin of each problem and compare them. If the other issues appear to predate the patient’s alcohol disorder [“I’ve been anxious all my life.”], they are more likely to be independent of drinking or an early motivator for alcohol misuse. In that case, there is increased need to work on the other issues early in treatment and not wait to see whether they abate as the patient regains sobriety. If the other symptoms are more recent, they are more likely to be independent of, or a consequence of the person’s drinking.

You can also ask for more details about the beginnings [time, place, reasons, social context] of the patient’s drinking problem, but the answers may not in themselves be helpful in establishing a dependency of drinking on the patient’s other psychological issues. Early drinking is often socially motivated or experimental, and changes later, as the person becomes more dependent on alcohol or uses it to deal with other problems.

INTEGRATING TREATMENT

There are many ways to work on alcohol misuse and other psychological issues, including the following:

- Look for connections between the patient’s alcohol use and his/her other psychological issues, and from time to time take the opportunity to shift focus from one to the other.

- Split the sessions and devote part of each session to each area or focus.

- Consider that a patient’s overemphasis and over-focus on either the psychological or the addictive area may be a defense against looking more closely at the other. This can be a clue about how the person operates to undermine his/her own life and treatment.

- Consider adjunctive treatment for some issues [See Section 19 ], so you can focus on others. It can be especially effective to refer out for formal training, classwork, or medical management of some issues, while paying more attention in session to issues that require greater psychological awareness and personal contact.

For further discussion of dual diagnosis treatment in an outpatient setting, see Perkinson , ch.6: 106-158. Treatment of substance abuse and several major personality disorders [antisocial, narcissistic, borderline and passive-aggressive] is discussed by Kaufman [1994, chapter 4] from a primarily psychodynamic perspective.

27f. The Patient’s Goals for Alcohol Use

Every patient has some idea about how best to manage the urge to drink, either as an explicit goal or plan or as an implicit and unformulated sense of what he/she wants in situations where temptations to drink are likely. It is important that the patient establish for him/herself an explicit personal goal regarding alcohol use in the future. That goal then becomes one basis for continuing treatment.

Goals probably make the most sense for patients in the preparation and action stages, when the patient has already decided that something needs to be done and/or is in the process of doing it. However, it also pays to press a patient in precontemplation or contemplation for some statement of a goal at this point, whatever it may be. The patient’s goals should be thoroughly understood by the therapist, so both are working in the same direction. A major source of patient resistance to treatment may be a consequence of a mismatch between the therapist’s direction and focus of treatment and the patient’s goals.

Different patients will have different goals, including –

- —continuing to drink as before, with all its attendant consequences.

- reducing alcohol intake somewhat, regarding quantity or frequency.

- controlled drinking.

- abstinence.

For most patients, the goal should be total abstinence, at least in the short run. Patients are seen for alcohol treatment because they have been out of control [whether they realize it or not]. The idea that anyone can quickly return to any form of controlled drinking is almost certainly mistaken, and the risks are great. However, whether a person chooses to be abstinent or not, it is important that he/she is capable of attaining and maintaining abstinence. Otherwise he/she is still an active alcoholic and under control of the drug.

Whatever the patient’s stated goal regarding alcohol use, it is important for you to know it and examine it with him/her. Here, a nonjudgmental stance is important, or he/she is likely either to leave treatment or to continue while lying to you about the extent of his/her actual alcohol misuse.

ABSTINENCE AS A GOAL

It is more likely at this point that a person is maintaining abstinence through effort, in the face of internal conflict and struggle with urges to return to drinking.

If the person has attempted to control moods or other symptoms with alcohol in the past, there may be changes in those symptoms or moods when drinking stops. Without the relief afforded by drinking, the person may re-experience unwanted symptoms or fear re-experiencing them, along with having urges to drink. These experiences may in themselves become clinical issues to be addressed in other ways, through greater self-awareness [ Section 37 ], through management of conditions and situations [ Section 25 ], or through some of the adjunctive treatments suggested in Section 19.

On the positive side, patients commonly report improvements in sleeping, increased ability to concentrate, reduced irritability, or less depression or anxiety over time. Often they are unaware of a connection between the change and their being abstinent. You can help them make the connection. Each positive change, when accurately attributed to abstinence, helps reinforce the patient’s motivation to remain sober.

In general, an alcoholic’s best plan is to remain abstinent each day throughout lifelong recovery. However, the concept of “lifelong recovery” is generally too overwhelming during the first 1-3 years. The focus must remain on each day. It is best not to be drawn into speculation regarding whether the patient will be able to re-introduce alcohol into his/her life at some future date. While it may be possible with some patients, with most it will not be, and to consider it at this point would be confusing and misleading. Focus on the present and avoid speculation about the future.

ABSTINENCE AS AN EXPERIMENT

If the patient has any goal other than abstinence, you could challenge him/her to go for an experimental period of abstinence, as a demonstration of his/her ability to do without drinking. For a person in precontemplation or contemplation, this can be presented as a test of whether the person can abstain, a kind of challenge to his/her assertion that alcohol isn’t a problem. For a person in the preparation or action stage, the issue can have to do with finding a way to abstain. Typically, a month is recommended, because it gives time for the person not only to get used to not-drinking, but also to developing other strategies when faced with the triggers that usually lead to drinking. This period of experimental abstinence can provide a great deal of information about how the person copes without drinking, and opportunities to work on additional strategies to bolster his/her efforts. If a person fails to remain abstinent, the lapse can also provide information – about kinds of temptations, strength of the urge to drink, possible alternatives to drinking, and so on.

If the person agrees to a trial period and can’t remain abstinent for a month, it is suggestive that he/she isn’t in control and should consider a serious commitment to abstinence until control is achieved. If he/she is able to remain abstinent for a month, then as the end of the month approaches, the issue can be raised of continuing for a longer period. It is possible that a review of the time will highlight enough positive changes in the person’s life or experience that he/she will want to remain abstinent.

- Some patients may need to begin with an extremely short period of abstinence, perhaps one night, or the period between sessions, in order to learn that they can.

- Most patients can recall periods of sobriety. You may be able to draw on those experiences as models for the present and evidence that temporary sobriety is possible.

ENCOURAGING A PATIENT TO ABSTAIN

There are many ways to do this. A few are listed below. Some others can be found in Washton and Zweben, page 165. Which you choose with a given patient will depend on a variety of issues, including the patient’s readiness for change [ Section 47 ], the patient’s personality and motivational level, external pressures, and your own comfort level.

Arguments for abstaining include:

- —Attempting to stop temporarily will help determine whether the patient can abstain without external assistance, and if assistance is needed, how much is needed. If the person is unable to stop temporarily, it may suggest greater dependence on alcohol than he/she has admitted so far, and may increase concerns that he/she can’t stop.

- A period of sobriety will allow you and the patient to determine whether there is a separate psychological issue or disorder (such as depression). If there is, then treatment can be directed toward dealing with that issue in addition to the patient’s alcohol problem.

- It will be helpful for the patient to experience even a brief period of sobriety, to find out what it is like, how he/she reacts, and what the pitfalls may be. It may also force the person to re-think his/her relationship to alcohol and lead to greater motivation to change.

If the person agrees to abstain for a trial period, you can plan the trial to maximize the probability of success. Preparation could include –

- anticipating, with the patient, some of the problems and difficulties that he/she may face in trying to abstain, and thinking about how to deal with them.

- recommending that the patient go to a regular self-help meeting, as a way of dealing with the urge to drink.

If a patient agrees to remain abstinent for a period of time or a set of circumstances and fails to do so, the natural question is what happened and why. The patient’s experience can provide information about whether to follow-up using either psychodynamic exploration [ Section 37 ] or behavioral management [ Section 25 ].

REDUCED, CONTROLLED OR MODERATE DRINKING

When a person who has been misusing alcohol wants simply to reduce his/her consumption and drink reasonably, he/she should be discouraged from doing so. He/she wouldn’t be here if not for misusing alcohol, and until things have changed substantially and reliably, the odds are great that he/she will return to former patterns. To some extent, this may reflect a wish to be “normal”. Most people drink in reaction to the social setting and norms: a glass of wine with dinner, a couple of beers while watching the game, and so on. Not to be able to do that with the same casual attitude as friends and family have can be narcissistically painful, and announcing one’s differences from others can be humiliating [“Oh, you’re not having anything to drink? What’s the matter?”].

Avoiding relapse is typically harder for a controlled drinker than for someone who is staying abstinent, because it is easier to fool yourself about drinking some than about drinking none.

A possible first approach to someone with this goal might be motivational interviewing [ Section 24 ], to help the person formulate goals and explore any ambivalence about drinking.

A patient may insist on controlled drinking for many reasons, and they are worth exploring [see Section 37 ]. However, he/she will do as he/she chooses, and you must work with your limitations here. It probably pays to be more watchful the greater the person’s prior level of drinking has been.

However, if you are unable to persuade a patient to be abstinent, you should maintain an attitude of benign skepticism, and encourage the person to report all successes and failures. Do not openly encourage patients to use alcohol “normally”, because his/her history of misuse is itself diagnostic of an inability to use it “normally”.

A “harm reduction” approach should be considered for any alcohol misuser who refuses to accept a goal of abstinence, and for whom the dangers are not serious enough to justify more radical treatment [such as involuntary commitment to a detox facility]. It is typically not the approach of choice for someone who has been alcohol dependent or abusive, but it may be the best that can be done. The general idea is to work with the person in incremental steps toward reduced drinking and reduced negative consequences of drinking, to involve the person in his/her own treatment planning, and to avoid creating requirements that will lead to patient failure or withdrawal from treatment. [Marlatt, 49-66; Seiger]. The ultimate goal is abstinence, but in the meantime, we work for whatever improvements may be possible [Rotgers, 192-3].

One well-researched approach, Behavioral Self-Control Training, has shown success with some patients. See Section 25 for more about this.

With moderation drinkers, an experimental period of abstinence can help the person get started in controlled drinking. [See “Abstinence as an Experiment”, above.] The suggestion can be made that a person who can’t go without drinking for a month can’t be sure that he/she is in control.

The plan to drink in moderation is easily compromised, with outcomes often unreported, and you should keep close account of the person’s successes and failures, lest he/she return to misuse without either of you noticing. In this case, a formal plan can be helpful. It should include a specific maximum amount that the person will drink each day. It should be written down, with a daily record of planned and actual alcohol consumption side-by-side for easy comparison. Hester [pp.154-155] provides a self-monitoring plan that includes a data card that a patient fills in each time he/she drinks.

Some initial issues that can be addressed in therapy while setting up a plan include:

- How will the person decide how much to cut back by or to? This can lead to questions of process, how he/she thinks and how effective that is.

- What is the basis of the standard that he/she is working toward? What are the reasons he/she has chosen these amounts and occasions? This can lead to issues of value, social pressures, personal history [“My parents always had a cocktail before dinner. It sets a relaxed tone for eating.”]

- What are the patient’s specific short-term and long-term drinking goals? Can he/she reasonably expect to do what he/she is planning without exceeding these amounts?

- How and will the patient gauge that success has been achieved; and when? This is good to have stated explicitly in writing somewhere, so it can be cited later on.

During the course of treatment, you can continually raise a number of issues:

- How well has the person been able to stick to the plan?

- If he/she is unable to stick to the plan, then why? What got in the way?

- If the person is able to stick to the plan, then how?

- Does the plan need to be revised to account for the person’s ability or inability to stick to it?

- Does success in sticking to a plan suggest that the person has the ability to be totally abstinent; or does failure to stick to the plan suggest that the patient should re-consider total abstinence?

DRINKING AS BEFORE

This goal is an extremely risky one. It includes all the risks of drinking in moderation, with the addition of an unwillingness by the patient to be monitored or controlled. The patient who ignores the risks is most likely in the precontemplation stage and is unwilling to see his/her drinking as problematic. However, whatever the stage, unaware drinking is a virtual prescription for relapse, and in general should not be supported.

To address this problem in the context of ongoing therapy you can –

- ask whether the patient has followed up on decisions made in therapy relative to other issues.

- ask about changes in related areas of his/her life that may make “normal” drinking a reasonable path to take.

- express concern about the continued drinking or skepticism that the person will be able to change other issues while still drinking. [“I want to believe that you can do this, but most people can’t.”]

You can also challenge the person to try abstinence or cutting back as an experiment and then note the consequences. If the person refuses to try a temporary period of abstinence as an experiment, then you have to decide whether to keep him/her in treatment with no control on alcohol consumption – or terminate him/her and move on.

While you may continue to treat such a person for other psychological issues, the effectiveness of such treatment is always in doubt. Dependence and abuse typically have an impact on a person’s ability to face important issues, making those issues effectively untreatable.

27g. Finding Alternatives to Drinking

If you can identify the needs or impulses that drinking services, it may be possible to find alternatives that work as well. While this should not be the only approach to use – it probably won’t be enough by itself – it can be helpful.

This is an area where behavioral and exploratory approaches can work together. Behavioral records can help identify triggers for drinking. An exploratory approach can then seek internal and external antecedents and cues that making drinking seem necessary, as well as uncover alternatives. Then behavioral techniques can be used to set up a program of substitute activities or reactions that preclude or interfere with the person’s drinking.

For example, a patient may realize that he drinks too much at family gatherings. Physical antecedents may involve holding a drink and sipping from it, and the goal may be to enjoy the party more. A behavioral plan might include always drinking a diet soda and enlisting one or more family members to monitor his drinking and get him another diet soda if he ever picks up a glass of beer or other alcoholic drink.

If the program is successful, its success can be explored and the program possibly expanded. If not, the reasons can be examined and other alternatives considered.

27h. Examining the Consequences of Drinking

It can be helpful to look at the immediate and long-term consequences of drinking for a person. Some people may not be aware of the consequences of drinking on their emotions, behavior, or interpersonal relations; and they may be surprised to discover that there are a variety of unintended negative outcomes to drinking – outcomes that, once they are noticed, become aversive relative to the whole process.

This can be done either formally or informally. Informally it becomes an exploratory exercise, in which the person tries to recall his/her experience of self and others as a consequence of drinking, then explores the meaning of that experience and its allure.

Formal techniques for gathering data tend to fall into the behavioral management sphere. A person can keep a record or diary of his/her moods on the days after drinking or not drinking and compare them. Sober friends can be invited to describe his/her drunken behavior or video it. A friend can agree to call the day after each episode to ask how he feels and record his/her response.

27i. Identifying the Risk of Relapse

There is always a risk of relapse with any alcoholic patient throughout treatment. This risk should be identified with the patient, discussed, anticipated as a possibility, and prepared for from the beginning of treatment.

A patient may have other concerns that seem more pressing and important: picking up lost pieces of a life, moving on. The possibility of relapse may seem remote to him/her. But an unprepared recovering alcoholic is at higher risk for drinking than he/she may realize. For more on this problem, see Section 33.

27j. Keeping Track of the Process Outside of the Treatment Session

Part of the problem here is whether you can trust your patient to maintain a recovery program and provide accurate information about it. The other part of the problem is whether you should attempt to manage your patient’s behavior or not. On the one hand, your patient may need you to police his/her behavior. On the other hand, he/she can probably find a way to get around you if you do. If you decide to monitor your patient’s recovery, here are some options.

SELF REPORT is useful as a source of information about the patient, but generally unreliable. Patients forget information and distort it for to a variety of reasons [hiding, trying to please, trying to look good, etc.].

ATTENDANCE AT MEETINGS can be monitored, either formally or informally. The patient may want to discuss issues that arise in the course of group participation; or you can ask what has been happening there from time to time. A more formal procedure is to have the patient report on each meeting. It is hard for a patient to fake the content of a meeting, especially if you have been to some and know what they are like; and the task of writing it all out is also helpful to some people. Having the patient collect someone else’s initials that he/she was there is some evidence of attendance, but it can easily be faked.

URINE CHECKS may be helpful, early in recovery. They can be done in a clinic or private practice setting. They may be a requirement for a patient who has been referred by the courts for an alcohol-related offense. They could also be voluntary, as a kind of external policing that you and the patient agree to, as an added inducement for him/her to stay sober. They must be done randomly, so the patient can’t manipulate your conclusions by being sober on days that he/she knows the screen will be done.

To carry out a test, collect a specimen from the patient, and arrange to have a local lab pick it up or send it to them. Alternatively, the patient can make his/her own arrangement with a lab near work or home, and you call on random days to have the test done.

WORKING WITH PEOPLE CLOSE TO THE PATIENT

When you work with families and significant others, you can help them monitor the patient, to watch for changes in him/her that might indicate a potential for relapse. They can provide additional information about events in the patient’s life and his/her reactions to them. Careful assessment must be made of the accuracy of others’ reports.

This work also provides the opportunity of keeping track of the others’ issues with the patient – enabling or codependent attitudes and behaviors, increased pressures on the patient, and so on. There is also a possibility that over time, the others will need additional help, either individually or with the patient, and adjunctive care will need modification.

WORKING WITH ADJUNCTIVE CARE PROVIDERS

Early in treatment this is a therapist responsibility: to keep track of the person’s contacts with other providers and ask their reactions to the patient. The patient can report his/her reactions to adjunctive care, including comments about the other professionals, other people in groups, and the side effects of medications. Some of these can be passed back to the other professionals as possible evidence for modification of care.

OTHER SERVICES

People with alcohol issues may have other unmet needs, including housing, health care, legal services, child care, and so on. You may be able to refer them to state or local agencies for help with these issues.