This section applies to a large number of patients, who have other interpersonal and intrapsychic disorders; and it could be relevant at any time during treatment.

A number of psychological disorders are commonly connected to alcohol misuse, as reasons for drinking, as consequences of drinking, or as interacting with drinking. Your choice of treatment must take into account the full range of the patient’s difficulties and personal resources, along with the availability of treatment. Diagnosis may be difficult, because similar symptoms can result from different disorders. Many authorities have addressed the issue of differential diagnosis when one component is alcohol misuse. However, with some patients it may not be possible to determine which symptoms to attribute to which disorder; and that problem also complicates treatment planning.

The presence of a comorbid disorder can increase immediate dangers to the patient and others, make treatment more difficult and less effective, lead to loss of patient control over his/her life, impair the person’s functioning and damage his/her health, lead to social conflicts and extreme behavior, and increase the risk of relapse of disorders thought to be under control.

The interplay of disabilities is often complicated. Alcohol use may be the patient’s way of trying to manage another condition, which could be physical, emotional or interpersonal. It may be a major component of a person’s defensive repertoire, a habit that has taken over a large part of a person’s life, or an attempt to self-medicate for a physical condition when conventional medicine is unavailable or ineffective. It can also cause other conditions or exacerbate them.

When a person is dealing with alcohol and some other condition, it is not always clear which disorder should be treated first, or whether they should be treated simultaneously. However, for a given patient, it is important to develop a plan that includes treatment of both. Treatment approaches typically follow one of three forms: sequential, parallel, or integrated.

In a sequential approach, one disorder is treated first, and when that is resolved, the other is handled. This can be effective if the first disorder is the reason for the second. Then if the first is treated effectively, the second is more easily handled. In some cases, the second may be resolved completely. For example, if the patient is using alcohol to manage pain, then medical treatment that relieves the pain may reduce the patient’s reliance on drinking. If a patient’s depression is a consequence of alcohol misuse, then the depression may lift somewhat after the patient has been abstinent for a couple of weeks.

In a parallel approach, different professionals treat different conditions at the same time. This can be useful if different specialization is required for the effective treatment of each disorder or if it is easier for the patient to work on the two treatment regimens in different treatment contexts. However, effective use of this approach typically requires regular contact among the professionals dealing with the different disorders, to ensure that they are making consistent demands of the patient.

In both sequential and parallel approaches, one underlying assumption is that each disorder can be handled effectively independent of the other. This may not be true.

For example, a patient may drink because he/she is depressed, then become more depressed as a result of drinking. To treat depression without treating the patient’s drinking would probably be ineffective, because drinking can lead to depression or increase a person’s experience of depression. At the same time, to simply tell the patient to stop drinking while the depression is being treated may also be ineffective – especially if the patient is in treatment because he/she is unable to stop drinking.

On the other hand, to treat a person’s drinking without addressing his/her depression could miss a significant contributor to the person’s drinking, and possibly make the alcohol treatment ineffective.

If you refer a severely depressed patient for inpatient treatment, the facility itself would force a period of abstinence, and at least some of the need to drink might be relieved if the treatment for depression is successful. However, there would remain a strong possibility that the person would drink on release, and that could precipitate a new episode of depression.

In an integrated approach, the same professional treats both disorders at the same time. When it is possible, this has the greatest likelihood of managing the interactions among disorders and ensuring consistency of treatment. In an outpatient setting, because of limited resources, it may be the only effective option. For more on this issue, see Mueser and Kavanaugh, 2004, p. 145.

Notable among common comorbid conditions are –

- medical conditions.

- other drug use.

- psychoses.

- personality disorders

- depression and anxiety.

- learning disabilities and attention deficit disorder.

Because treatment must address both disorders, it is important to assess patient motivation relative to both issues [Mueser and Kavanagh, 2004 139]. This may be difficult to do at the beginning of treatment, and patient motivation may only become clear as time passes. As Orlin, O’Neill and Davis [2004: pp. 110-111] point out, both serious psychiatric disorders and alcohol misuse are commonly associated with low motivation for change. They recommend looking for treatment leverage: compelling reasons that the patient has for coming to therapy. You might be able to engage a person in treatment by involving other family members, making professional contact with the person’s physician or attorney, contacting a local housing authority on the patient’s behalf, or providing records of attendance for court-mandated therapy If so, those services may serve as levers to encourage regular therapy participation by the patient.

It is important to work on the relationship between patient and therapist at the beginning of treatment, along with establishing a clear set of treatment goals and the working alliance. The need to engage unmotivated patients is a major component of motivational interviewing, as described in Section 24.

Mueser and Kavanaugh [2004, p.143] recommend assessing patient insight into both disorders, along with motivation to work, in order to begin treatment in an appropriate place. However, this does not mean that treatment is limited to insight- or motivation-based interventions. It simply implies that the treatment plan will need to depend on these variables in order to be effective.

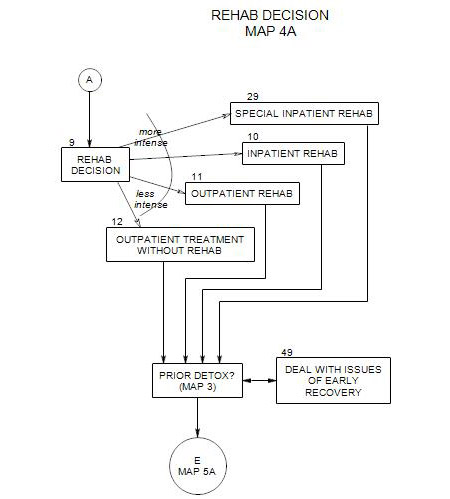

It is also important to assess the severity of both disorders in order to decide about the intensity of treatment needed, including the choice between inpatient and outpatient treatment. Some of this is covered in Section 7 [relative to detox choice], Section 9 [relative to the rehab decision], Section 14 [in picking the form of primary care] and Section 19 [when choosing adjunctive care].

One possibility for conceptualizing the problem is to create a table which has a columns the two [or more] disorders and as rows some of the major issues affecting treatment. Then comparison of the columns of the table can be helpful in deciding which disorder is primary, which disorder needs to be considered first, which issues if addressed will be helpful for both disorders and which will help on and not the other, and so on.

For a patient with both depression and alcohol misuse, such a table might appear as follows, having as many rows as needed to show the patient’s issues:

Depression Alcohol

- Age of onset early childhood about 13

- Family history mother was depressed father drank heavily every night

- Abusive if drinking

- Triggers being alone being depressed

- Losses

Orlin, O’Neill and Davis [2004] provide such a table for a patient diagnosed with schizophrenia and multiple drug use.

8a. Medical Conditions:

Drinking serves many purposes for people, some of them medically related. Some people use alcohol to manage pain, whether it be episodic or chronic, and in some cases it can be an effective analgesic. People drink to forget their physical limitations, to deal with medically related isolation, and for many other reasons. There can be layers of issues, as when a person is treated for cancer, then becomes depressed about the possibility of recurrence, and drinks in reaction to the depression.

Alcohol use can also worsen medical conditions, hide serious medical issues, and compound with some disorders to cause dangerous complications. In some cases, as with diabetes and hypertension, it can be lethal. If you haven’t already collected information on the patient’s medical conditions and drug usage, this might be a good time to do so. A patient with multiple medical conditions and multiple medications can have a confusing symptom picture. It is always better to know as much as possible, even if the whole picture is confusing, than to treat symptoms that are caused by a source you are unaware-of. With some medical problems or treatments, it may be helpful to contact the patient’s physician for a fuller picture of symptoms and medication side effects.

Even if a person’s medical and alcohol disorders have independent origins, we still have to be concerned about interactions between the person’s alcohol use and either his/her other medical condition or the treatments used to manage it. Alcohol also interacts with many prescription drugs, either to amplify or reduce their effects. The interaction is unpredictable, depending in part on the amount the person drinks.

It is important to keep track of:

- all medical conditions the person has;

- any medications the person uses, amounts, and frequencies; and

- how much the person drinks, how frequently, on what occasions, etc.

Treatment includes referral for adjunctive care, either to a physician that the patient is already using or another who can be helpful, along with some kind of contact with the physician. If there are any likely complications here, then you should be in ongoing contact with the physician about the issues and possible ways to reduce risks and improve treatment effectiveness.

8b. Dual or Multiple Addiction:

It is helpful to ask at intake and regularly throughout treatment about all drugs the patient may be using, whether prescription, over-the-counter, or recreational – whether or not the patient thinks the use is significant. The exact names of the drugs and daily use pattern will be important to know, along with any recreational drugs of choice and some indication of the patient’s reason for that choice. The total profile of use will affect your treatment planning, whether the patient is seen as an outpatient or is referred for detox or rehab.

There are many dangerous drug combinations. For example, a person who uses cocaine with alcohol may get into his car at the end of the evening feeling alert and in control, then fall asleep at the wheel on the way home, when the effects of the cocaine wear off.

A table for the comparison of a person’s use of alcohol and cocaine could contain rows that include occasions for use, triggers, age of first use, expected consequences, actual consequences, and so on. [See Orlin, O’Neill and Davis, 2004 p.108 for an example form.]

Treatment of multiply addicted people depends on the severity of addiction to each of the substances used. While the details of treatment vary for different substances and combinations of substances, the choices follow the same format as for alcohol treatment. Deal with safety issues first, then decide on the need for detox and/or rehab. If inpatient treatment isn’t necessary, consider outpatient therapy.

8c. Psychoses

People with schizophrenia or other psychoses can become dependent on alcohol for a variety of reasons. A patient may drink to relieve internal pressures – voices in his/her head, fears of being followed or watched, and other perceived dangers or intolerable annoyances. If the person’s psychosis interferes with daily living and can’t be managed on an outpatient basis, inpatient placement may be necessary. If so, the person should be treated in a dual diagnosis facility, rather than a regular psychiatric hospital or alcohol treatment program, because the responsibilities of staff include explicit work with both disorders.

If a person’s psychosis is a consequence of alcohol [and drug] use, then inpatient treatment in a drug and alcohol facility may reduce the psychiatric symptoms enough that psychotherapy can be helpful later on. However, such patients generally require long-term inpatient care and have a high probability of relapse on release.

Outpatient treatment is possible for many patients, once they are stabilized. However, they typically need a variety of adjunctive care, and they are prone to relapse with either disorder. An alcohol relapse could trigger a psychiatric collapse, and vice versa. Ongoing contact among professionals is essential.

8d. Personality Disorders

The personality disorders most often associated with alcohol misuse include antisocial personality, borderline personality, narcissistic personality and passive-aggressive personality [Kaufmann, 1994, chapter 4].

Outpatient treatment of people with personality disorders is discussed by Kaufman, who adapted the recommendations made by MacKinnon and Michels [1971] for the same disorders in nonalcoholic patients.

8e. Depression and Anxiety

During treatment for alcohol misuse, many patients who initially present with anxiety or depression appear to recover spontaneously from their psychological disorders. This suggests that their anxiety or depression may be a side effect of alcohol, and that further treatment is unnecessary [Mueser and Kavanagh, 2004 149a]. If alcohol use can be established as the primary disorder, and if inpatient treatment is necessary, then there may be justification for treating the alcohol issue first and any anxiety or depression once sobriety is established. It is typically not enough to put a patient through detox or detox and rehab, and then to expect that his/her alcohol and mood issues have been treated. Lingering untreated anxiety or depression can continue to serve as a trigger and a justification for relapse.

In an outpatient setting, however, it is generally safer to provided integrated treatment if possible. Both disorders are serious, both should be treated seriously, and a lapse in either could lead to a relapse in the other. Treatment of anxiety and depression should follow the general procedures used when alcohol misuse is not a problem.

DEPRESSION

There are many forms of depression, including dysthymia, major depression, bipolar disorder, and seasonal affective disorder. Any of these can be associated with alcohol use by some patients. A severely depressed person who uses alcohol can be at risk for suicide or dangerous behavior.

Depression can lead to drinking in various ways, including drinking to –

- feel better, possibly the way the person remembers feeling when drinking in the past.

- show others just how depressed he/she really is.

- feel more depressed – to “wallow in it”.

- “numb out” and not feel anything.

- distract him/herself from the depression – to have a good time.

- express hopelessness: “Sure, why not? Who cares?”

However, drinking doesn’t resolve any of the sources of the person’s depression and at best offers temporary relief; so the issue recurs and the person continues to drink. At the same time, alcohol is itself a depressant, the lack of long-term change can be depressing, and the side effects can interfere with other aspects of living.

Although alcohol misuse could be the consequence of a person’s attempt to self-medicate for depression, it is risky to assume this order of causality for treatment purposes, even when the patient believes it to be true. Any attempt to treat the depression alone – with psychotherapy or medication – would lead to two serious difficulties: [1] successful treatment of the depression could leave the alcohol misuse unaffected, with its own dangers plus the danger of recurrence of the depression; and more importantly, [2] alcohol misuse interferes with the treatment of depression, in part by reducing motivation for psychotherapy, and in part by interfering with the effectiveness of antidepressants.

For these reasons, it is important for a depressed and alcoholic patient to stop drinking before beginning any medication for depression. Once a patient has been abstinent for two weeks or more, persistent depression often may be alleviated with an antidepressant. Then if the depression lifts and the patient is able to continue abstaining, treatment can change focus to other issues. If the patient is unable to maintain sobriety, medical treatment of depression may not be an option.

ANXIETY

Drinking can be associated with a wide range of anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia and post traumatic stress disorder. In most cases, alcohol is used to temper the anxious feelings and either allow the person to function or to withdraw and not have to function. [Jarvis etal, 294-6]

If the person is able to stop drinking for a period of two weeks or more, and if the anxiety abates, it is likely to have been a consequence of alcohol use. Treatment can then focus on continued sobriety, with less concern about anxiety.

If the anxiety or depression poses an immediate threat to the patient or others and the patient is not able to stop drinking for the time needed for assessment, hospitalization may be indicated.

There might be a temptation to try anti-anxiety medications with an active alcoholic. However, at best the treatment wouldn’t address the source of the patient’s anxiety and might undermine recovery; and you risk synergistic, potentiating effects from compounding depressants. This could lead to increased inebriation (and increased risk due to impaired judgment), overdose, and possible death.

If a patient continues drinking and needs outpatient treatment, some pharmacological relief can come from antidepressants or Buspar (Gitlin, p.155). If you think this path is necessary, send the patient to a psychiatrist, and call ahead, indicating your concerns about medication in the presence of alcohol.

A person with a PANIC DISORDER has experienced a series of spontaneous panic attacks. He/she is likely to be chronically upset about the attacks and awaiting the next one anxiously. Alcohol may be seen as a way to avoid the next attack, or sometimes, to manage an attack. It is typically ineffective at both. The person may also be using alcohol for other reasons.

The first order of treatment for panic disorder is to manage the attacks, commonly with a high potency benzodiazepine, beta blocker, or antidepressant. However, these can be dangerous in combination with alcohol. The person should be referred immediately to a psychiatrist who knows of his/her drinking, to determine if medication can be used under the circumstances.

Ongoing treatment is similar to treatment for patients who are not drinking, including stress reduction, finding and avoiding triggers for the attacks, and exploring the patient’s history for long-term antecedents.

Panic disorder can be treated psychopharmacologically with either anti anxiety medications or antidepressants. The former give more rapid relief but have serious risks, as just indicated.

The comorbidity rate of BIPOLAR ILLNESS with alcohol abuse is very high: people who have a bipolar disorder are far more likely than the general population to have an alcohol abuse problem.

A person having the most intense form, Bipolar I, should receive acute treatment in a dual diagnosis program (or minimally, in an alcohol treatment program that allows for medication for other conditions). However, with effective medication, many people having this diagnosis are able to manage their lives effectively and make good use of outpatient psychotherapy.

8f. Learning Disabilities and Attention Deficit Disorder

LEARNING DISABILITIES can lead to stress, low self esteem, social isolation and depression, for which some people self medicate with alcohol. Long-term daily consumption of alcohol also leads to decreased cognitive functioning, and a possible downward cognitive and emotional spiral.

ATTENTION DEFICIT DISORDER: As commonly used, this is an umbrella category for people with a variety of underlying difficulties that result in problems with concentration, hyperactivity, poor performance, and in many cases, conflict with authority figures. By adolescence, it can lead to social isolation or rebellion, depression, drug and/or alcohol use. As with other disorders, self-medication with alcohol can lead to temporary relief and long-term exacerbation of the person’s ability to focus.

Form of Treatment

Because alcohol use can cloud the diagnostic picture, when a person is taken into treatment and reduces or stops drinking, regular re-assessment is an important part of the process.

Whether you work with a dually diagnosed patient in an outpatient setting or refer for inpatient treatment depends of the severity of the psychological or medical disorder, the severity of the person’s alcohol problem, the extent to which his/her life is disrupted, the dangers involved in maintaining the person in the outside world, and the resources available for treatment.

When referring for inpatient treatment, note that some programs only treat alcohol issues; others handle multiple addictions.