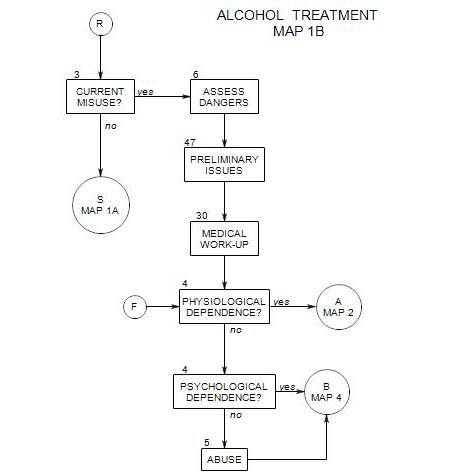

47. PRELIMINARY ISSUES IN TREATING AN ALCOHOL MISUSER

- This section follows a determination that a patient is misusing alcohol from Section 3. It provides background for determining the patient’s type of misuse and other early treatment decisions on Maps 2 – 4.

This section covers some of the information needed in treating a new patient who may be misusing alcohol. It is intended to be integrated into the therapist’s usual early diagnostic and treatment procedures. The parts of this section include:

- The patient’s stage of change relative to alcohol use

- The patient’s stage of change relative to other issues

- Consequences of alcohol misuse

- Topics to pursue with an active alcoholic

- Information relating to the reason the person has come for treatment

- Information bearing on the detoxification decision

- A graded sequence of treatment alternatives

- Other useful information

If you are going to work with a person who misuses alcohol, it is very important to make him/her feel safe with you, even when admitting misuse and lapses in meeting goals for controlling alcohol use. Like any other treatment issue, if a person can examine alcohol use closely and carefully there is a greater opportunity to change it. Perhaps more than many other issues, alcohol use is commonly seen as intentional, and misuse as a sign of weakness, self-indulgence, lack of character, etc. One consequence is that many alcoholics are reluctant to admit their misuse and likely to understate it. Others are ambivalent about stopping and fear pressure to stop if they tell the full extent of their use.

Here the working alliance is crucial. Therapist empathy and support allow a person to admit and discuss the amount he/she drinks and consider modifying his or her drinking behavior.

The long-range goal of treatment is for the person to learn to avoid using alcohol to the point of negative consequences. For most people, this means total abstinence.

Some initial goals of treatment include –

- helping the person begin or stay in treatment. You can’t help a person who is somewhere else.

- trying to minimize harm from misuse of alcohol.

- helping the person become more aware of his/her alcohol use and its consequences.

- assessing the person’s readiness for change

- most likely, moving him/her toward a goal of abstinence.

- working on the person’s other psychological issues. Explore them as much as you can in the context of the person’s stated goals for treatment.

47a. Patient’s stage of change relative to alcohol use

If there is clear evidence that a person is misusing alcohol, the natural next step is to begin to plan for change, to help the person reduce alcohol use to a point that it is no longer a problem. However, planning for change must take into account the person’s experience of his/her misuse and his/her ability and willingness to change.

Prochaska, etal (1992, 1102 – 1104; see also Connors, Donovan and DiClemente, 2001) have described a continuum of change that can be applied to a wide range of addictive behaviors, having five stages in the path from full addiction to recovery. The stages are:

1. Precontemplation

2. Contemplation

3. Preparation

4. Action

5. Maintenance

This is a good time to begin assessing the person relative to his/her place in this continuum, so treatment can be consistent with the person’s ability to use it. Treatment that is inappropriate to the patient’s place on this continuum is likely to be ineffective. Treatment that is appropriate is more likely to be helpful.

To gauge a person’s status relative to the five stages of change, first gather evidence that the person is misusing alcohol. The evidence could be in many forms: a history of fighting when drinking, one or more arrests for driving under the influence of alcohol, reports from spouse or others close to the patient, or the patient’s own reports of his/her drinking quantities or patterns.

Once you have enough data to show a pattern, you can present it to the patient and note his/her reaction.

A person in the precontemplation stage doesn’t see a problem with his/her drinking and has no felt need to change or intention of changing. He/she may be unaware that his/her behavior is a problem, or unwilling to do anything about it, or discouraged about making changes in it. This stage is commonly called “being in denial” by professionals who work with alcohol misusers, although the term “denial” is also broadly applied to a range of behaviors in which a person fails to appreciate the negative consequences of his/her misuse. When asked about the evidence that his/her drinking is a problem, a person in this stage will respond in ways that deny the truth of the evidence or minimize its importance. In addition, he/she may be irritated or angered by the perceived accusation and impatient to move on to more important topics.

A person’s defenses against admitting the importance of drinking may take many forms, including

- Justifying behavior: “I was just standing there having a beer, and he bumped into me intentionally. I couldn’t let him get away with it.” Or: “The visibility was bad, it was night, and I just didn’t see the car parked in that stupid place.”

- Attributing the problem to something else: “Of course she said that about my drinking, because she doesn’t want to talk about our sex life.”

- Denial of the possibility of change: “I’ve tried everything. It doesn’t work.”

- Flat-out denial: “It’s not true. I drink very little, and it has no effect on me. I just like it.” Or “I cut back already. I only drink a couple of six-packs a night now.”

For more discussion of defenses, see Section 34. Whatever form a person’s denial takes, it is safer not to challenge it until the patient is committed to treatment, trusts the therapist, and is prepared to examine him/herself. It is better to accept the person’s assessment of his/her status and move on to gather more information.

A person in the contemplation stage is aware that there is a problem and is considering change. However, he/she is ambivalent about taking action and can’t make a commitment to doing so. A person in this stage won’t immediately or completely dismiss the possibility that he/she drinks too much; but he/she won’t address it directly either. When faced with evidence of alcohol misuse, he/she may procrastinate or equivocate without ever taking action. At some point, he/she may search for information about it.

There may be a reluctant acknowledgement of a problem, as in “Maybe I do drink too much some times, but -” This much helps place the person in the contemplation stage, and the rest of the sentence can give information about his/her defenses. He/she may wonder if the consequences are serious enough to give up drinking, or whether other issues should be addressed first. Giving up alcohol may appear to require giving up other important things as well: friends who drink, places he/she likes to hang out, parties, and so on.

A patient in the preparation stage is committed to make a change in both attitude and behavior, and may be beginning to make small, often ineffective changes. He/she may have cut back on drinking a little, but not enough to have a serious effect, e.g. -.

- putting off the first drink from 10 AM to noon.

- cutting back from eight drinks to six.

A patient may fully intend to do something about drinking but hasn’t decided what it is. There is no overall plan; and if you ask, he/she can’t say what the next step is, or when it will begin. Here, you can ask what he/she did in the past, what the desired effect was, whether it was achieved, what other treatment options he/she considered in preparing to change, etc. This can all be done in a context either of neutrality or encouragement, depending on your assessment of possible impacts on the person’s behavior and the treatment alliance.

A patient in the action stage is working directly and actively to change drinking behavior, environment, and/or experiences, in order to deal with problematic drinking. He/she has chosen specific goals to drink less and is working toward them. When you ask, these goals can be articulated, along with plans for achieving them. He/she is aware of potential impediments and barriers. A person may actually have stated those plans publicly and may have sought help from family, friends and support groups. He/she is working at drinking less and determined to succeed. Information gathering can include discussing the patient’s goals and plans for managing the misuse, making note of what has been done so far in the service of those goals, and asking about next steps.

When a person is in the maintenance stage, the gains of the action stage are consolidated and further work is done to prevent relapse. The patient solidifies gains and learn new ways of managing without drinking, ways that are inconsistent with drinking. This is the eventual goal of treatment for all misusers.

47b. Patient’s stage of change relative to other issues

People go to a therapist for many issues, some of which may not even surface until they are actually in treatment. One issue may be alcohol misuse, although it is less likely than others. Most people think of drinking as benign, or as a solution to their problems, or as one of many problems – if they think about it at all. Other possible issues are many and varied: relationship problems, anxiety, depression, conflict about work, sex, where to live, and so on.

It can be helpful to gauge a patient’s stage of change relative to each of the issues that come up, as part of overall treatment planning. The same person may be in precontemplation relative to drinking but action relative to depression or to a relationship. Focus on the issue of current urgency to the patient can be valuable in its own right, and at the same time provide an entry point to increasing the patient’s awareness of a drinking problem.

47c. Consequences of Alcohol Misuse

It can be helpful at this point to ask about the consequences of drinking in the patient’s life, for better or for worse [see motivational interviewing, Section 24 ]. The questions can be open ended and you may not want to press the person for awareness that isn’t there yet. Ask if it has affected –

- work.

- family relationships or responsibilities.

- finances.

- mood.

- relationships with friends or neighbors.

- legal matters.

- social functioning.

- other medical or physical issues.

- sexual activity or functioning.

The person’s responses to this line of questioning can lead in to your assessment of his/her readiness for change.

47d. Topics to Pursue with an Active Alcoholic

If you decide that a person is an active alcoholic, the nature of the interview may need to change.

An alcoholic, whether or not he/she admits to misusing alcohol, will almost always avoid direct discussion, either of the problem or the extent of his/her involvement with it. As sympathetic therapists, we may follow their lead in order not to create discomfort for them. We also may prefer to deal with the patient’s other issues: they are psychologically more interesting. And we would like to believe that the patient is telling the truth and actually is doing better.

There is a danger of being limited by the patient’s agenda, [e.g.: being under pressure, being misunderstood, being angry at others, etc.] and not pursuing alcohol related issues. The patient’s drinking may be a major source of the other issues that the patient wants to address. Although you may need to hold back on pursuit of a patient’s alcohol use in order not to drive him/her out of therapy, you also need to note times and places that drinking could be a problem, and follow up whenever feasible.

47e. Information Relating to the Reason the Person is Here

If the person came voluntarily, then you will want to know why:

- What issue or issues led him/her to therapy, and whether he/she perceives them as alcohol-related.

- Why he/she came to you.

- Why he/she is coming now; and especially, whether there is a crisis of some kind that needs to be addressed before therapy can continue.

If the person came under pressure from other people, then you have a different set of issues to deal with, especially having to do with –

- who insisted that the patient come and why. Whether the patient agrees with that reasoning, and why or why not.

- whom you are working for. There is no reason to expect cooperation from the patient if he/she sees you as working for someone else, such as the patient’s family or the court system.

- what goals for treatment you and your patient can agree upon.

- confidentiality and its limits: information you must report and information you should not share with others.

- how to deal with the people who are providing the pressure.

- whether the person is angry, defensive, withholding, or suspicious, and if so, what the details are.

- whether you can work together, and if so, around what issues?

- what the consequences may be if steps are taken to change the person’s drinking pattern – to others and to the patient.

- what the consequences will be if no change is made – to others and to the patient.

If treatment was mandated, –

- all the considerations of pressured treatment come into play, in addition to issues of institutionalized authority.

- you need to be clear with yourself and with the patient what your responsibility is to the mandating agency, including the nature of any reports that must be submitted.

- you should be clear with the patient that there may be a conflict between openness in the sessions and your responsibilities to the mandating agency. Then you should decide whether you can work effectively within the limitations of the mandate. Your job is to help the person comply with the mandate while being honest in reporting.

47f. Information Bearing on the Detox Decision

These questions relate to the issues of whether the person is physiologically dependent on alcohol [ Section 4 ].

Ask how much the person drinks in varying circumstances.

- Does he/she drink every day? If so, how much? Are there any negative consequences of this habit, and if so, what are they?

- Does he/she drink in the morning? -every morning? …during the day?

- Is the drinking regular or episodic?

- Has the person been able to stop for several days or more? If not, he/she is a likely candidate for detox.

Ask how long the person has gone without drinking. If he/she has been able to go for two weeks or more, that’s a good sign. Then ask if there were withdrawal signs. If not, that is another good sign, with regard to the intensity of the person’s drinking. If the person hasn’t been able to go more than three or four days because of shaking or other withdrawal signs, then he/she will probably have to undergo medically supervised detoxification in order to stop safely and effectively.

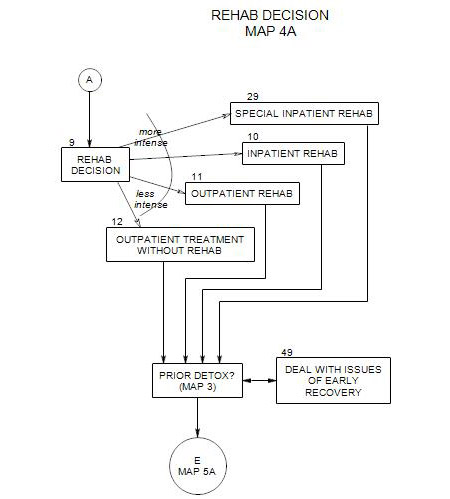

47g. A Graded Sequence of Treatment Alternatives

Generally, when planning treatment, you try the least disruptive or intrusive solution that is likely to be effective first, then move to more restrictive or controlling treatments if the first one fails. Less intrusive treatments may be effective with patients who have more self-control about drinking. However, when a person is unable to manage his/her own life effectively and is dangerous to self and others, then more restrictive and controlling treatments may be justified.

We can rank order alcohol treatments from least to most intrusive [roughly] as follows:

- Self-control without treatment

- alcohol counseling

- AA attendance

- outpatient psychotherapy

- outpatient detoxification or rehabilitation

- inpatient rehabilitation

- inpatient detoxification

When it comes to deciding on the level of treatment, it can often be helpful to involve one or more significant others in the process, both as “reality-checks” in evaluating information about the patient and possible allies in the treatment.

47h. Useful Information

The following questions are categorized, but the sequence in which you ask them should follow the flow of your interview with the patient, rather than be used as a checklist to be gone through. Washton and Zweben (2006, pages 152-156) list some additional questions that can be useful in assessing a patient’s readiness for change. How this information is used may or may not be obvious at this time; and you may want to put off asking about it until it seems more relevant.

MEDICAL INFORMATION

Medical information can be useful as background in understanding a patient’s need to drink and the impact of alcohol on a patient’s life. It can also be helpful to have on hand when talking with the patient’s physician [ Section 30 ] or other specialists. Because of time pressures and their professional orientation, physicians may not be aware of information about a patient that you know is important. Having it on hand and calling may change the physician’s understanding and alter that part of treatment.

Medical information especially relevant to alcohol misuse can include –

- the patient’s history of injuries, accidents and diseases.

- any history of head trauma, including the circumstances and whether the person was unconscious.

- any hospitalizations and their consequences.

- any history of gastrointestinal bleeding, gastritis, pancreatitis, hepatitis, strokes, jaundice, acid reflux, weight loss, blackouts or DT’s.

- any chronic disorder that might tempt a person to self-medicate: especially chronic pain, sleep issues or recurrent reactive pain.

CONTEXT OF DRINKING

You can better understanding a person’s drinking behavior if you have information about –

- use of alcohol by family members and at family gatherings

- general attitudes about drinking within the family

- the patient’s reactions to others who drank and pressures to either drink or abstain.

- neighbors and neighborhood drinking and the patient’s reactions to them.

- regular opportunities and temptations in the patient’s life.

HISTORY OF DRINKING

- Ask when he/she first began drinking and why. Ask if there were any milestones in his/her drinking history – changes in his/her drinking pattern.

- Ask if he/she remembers getting drunk the first time. A drinker will often remember that experience in great detail. Many alcoholics got drunk the first time they drank.

- Ask about periods of sobriety. When were they, and why and how did the person stop? How long was the person sober, and why did he/she return to drinking?

- If the person is high school and/or college-educated, ask what happened in school and with schoolmates relative to drinking. It helps you establish the progression of the problem. You can also look for other milestones in the person’s personal history and ask if his/her drinking patterns changed at those times.

PRIOR ALCOHOL TREATMENT

Ask whether the person has ever undergone detoxification or been in a hospital or inpatient program for treatment. If so, details are useful:

- Why did he/she go for treatment?

- Was it voluntary?

- How many times was he/she treated?

- Did he/she ever detox him/herself? How did it go?

Then for each detox or rehab, ask:

- Was it completed?

- How effective was it?

- What about it was effective and why?

- What about it was less helpful or harmful?

- How long was the person sober after detox?

- How did he/she stay sober?

- What led to relapse?

Ask whether the person has participated in any 12-step programs in the past. If so, then ask –

- when and for how long?

- whether he/she did the steps, and if so, what happened?

- whether he/she had a sponsor, and whether the sponsor was helpful.

- whether he/she spoke up at meetings.

- whether he/she is still going. If not, then when did he/she stop and why?

These questions give a lot of information about the person’s recognition of having a problem and taking action to deal with it. They also bear on the use of 12-step programs as adjunctive in current treatment.

PRIOR PSYCHOTHERAPY

In any psychotherapy, it is helpful to know about a patient’s prior treatment:

- When it happened – how long ago and/or at what ages.

- What the issues were.

- Who the therapist was, and the patient’s reaction to the therapist.

- What type of treatment it was, for outpatient therapy.

- How long he/she went each time, and why.

- Whether he/she had any inpatient treatment for psychological issues.

OTHER DRUGS

Ask about other drugs the patient has tried and may use regularly or occasionally, both prescription and over the counter.

- Does he/she take any prescription medications? If so, which ones? Get their names, dosages and times. Why does he/she take them, and are they effective? When did he/she start, and who prescribed them? It may be helpful to get the names and telephone numbers of prescribers and to contact them about the patient and the medications prescribed.

- Does he/she use any over-the counter medications? If so, when, why, and how often?

- Does he/she use any other street drugs? [This could include marijuana, heroin, pills, etc.] How often? For what purpose, and on what occasions?