- This section is background to many of the discussions throughout the text, although it doesn’t appear on the maps. It is cited in Section 47, Section 20, Section 27, and elsewhere.

It has long been clear that treatments for addictions are effective for some people and not for others, and there have been different theories for treatment failure. Often the addict was blamed – he/she was morally weak, or not ready, or unwilling to change, or self-destructive, or too well defended. Prochaska, Diclemente and their collaborators (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1986; Prochaska, Diclemente & Norcross, 1992; Connors, Donovan & DiClemente, 2001) have developed an alternative theory around the notion that treatment success or failure depends in large part to the extent that the treatment matches the patient’s level of readiness for change. They specify several levels of readiness for change, going from total denial through awareness of a problem, readiness to work on it, successful treatment, and maintenance of gains made. While this is seen as a continuum, it makes sense to divide the continuum into five stages, listed below. When different approaches are used with patients in the different stages, treatment is more effective.

It is also recognized that people fluctuate from session to session and even within a single session. An ongoing re-evaluation of the patient’s level of change is important for treatment to remain relevant. Whatever the patient’s position on the continuum of change at a particular moment, the therapist’s job remains one of helping him/her move to greater awareness and eventually to action.

The following is organized around the kinds of treatment that patients can make use of according to their stages of change. For other discussions of this topic, see Washton & Zweben (2006, 170-173) and Connors etal (2001).

PRECONTEMPLATION OR DENIAL

Here, the person sees no problem with his/her drinking, or refuses to focus on the problem. Or he/she may admit to drinking more than other people but deny that it amounts to misuse. At the same time, the person’s drinking may present dangers to him/herself and others, lead to inefficient or ineffective actions, affect his/her self esteem, and so on, so that something should be done. In addition, the person’s misuse can undermine psychotherapy, particularly if it is not recognized or addressed by the therapist. It becomes a hidden influence on the patient’s feelings, thoughts, relationships, etc., possibly leading the therapist into a futile pursuit of irrelevant issues.

However, it is very unlikely that pushing a person into taking action when he/she is in precontemplation will be effective. What is more likely is that he/she will argue, refuse to participate, and possibly leave therapy. If you want to raise a patient’s awareness of alcohol use and its effects, you will need to proceed with caution.

This raises at least two questions: [1] What will allow the person to continue treatment and not drop out? [2] How can treatment be helpful, if it is likely that much of his/her symptomatology is a consequence of drinking, and he/she doesn’t recognize a problem in drinking?

The short-term goals for a person in precontemplation are: first, to keep him/her in treatment and working, and second, to move him/her into contemplation, i.e.: into awareness that there may be a problem in his/her drinking, into active ambivalence and into open consideration of the possibility of change.

The first step may be to determine what he/she sees as the real problem – the reason that psychotherapy seems necessary. Relative to this issue, the person is in the action stage and wants help with it.

He/she may perceive the issue as external: pressure from family or the legal system, job problems, circumstances and bad luck, being misunderstood by others, etc. The person’s experiences and explanations can be explored in detail, using approaches from motivational interviewing or supportive psychodynamic therapy [ Section 37 ]. While he/she is working on that issue, there may be opportunities to increase his/her awareness of the impact of drinking on it. You can also devote part of treatment to determining the amount that the person drinks, occasions for drinking, the effect sought, the actual effect, the meaning of alcohol, the significance of alcohol in the patient’s life, and so on.

If the person is coming under protest, you may be able to sympathize with his/her reactions to the pressure. If pressure is unavoidable, try to forge an alliance around making good use of your mandated time together, to deal with other issues that the patient thinks are important. Some patients are relieved to hear a comment such as “I’m not here to shape you up; besides, we both know that wouldn’t work. But since you have to come for a while, why don’t we see if there is something we can do that would be helpful to you?” This can on occasion begin a treatment alliance and lead to better patient understanding of what therapy is helpful for, how it works, and so on. It also empowers the patient by involving him/her in treatment planning.

If the pressure is less intense and coming from family members, one or more couple or family sessions may be helpful, to clarify their concerns without necessarily committing you to join either the pressure or the patient’s resistance to it. Such a session could provide incentive for psychodynamic work after the others leave, or it could lead to the addition of couple or family therapy as adjunctive treatment.

A patient may not be willing to continue with treatment of any kind. In this case, termination [ Section 28 ] may be the only option.

If the person is willing to continue, behavioral treatment for drinking is not likely to be helpful, because it assumes a conscious cooperation from the patient towards managing a problem that he/she doesn’t see as a problem. Some work an still be done on the person’s other psychological issues using a psychodynamic approach, with the person’s alcohol misuse a topic of discussion as it arises in the course of therapy. However, depending on the patient’s drinking level, therapy that works to uncover repressed material may be relatively ineffective. However, supportive therapy or motivational interviewing [Section 24] may help the patient remain in treatment and begin to recognize the work that needs to be done.

Management of the treatment may be important for this patient – staying in contact with adjunctive providers and coordinating the various aspects of the patient’s treatment. It is possible that efforts to help the patient recognize and treat an alcohol problem can be more effective if they come from several different perspectives.

If in the course of psychotherapy a patient comes to admit misuse, you may need to revise treatment to deal with this awareness by exploring the issues of Section 37 above. At the same time, it might be wise to re-consider adjunctive treatment [ Section 19 ] as well. A person’s awareness of alcohol misuse may be raised in a variety of ways through adjunctive care. For example, a physician referral may uncover medical abnormalities that are related to alcohol use; or participation in a therapy group for emotional issues may result in confrontations about drinking from other group members.

CONTEMPLATION

A person in this stage is considering change and/or making tentative first steps toward change. However he/she is ambivalent, and can’t make a commitment to it.

The short-term goal for such a person is to help him/her move on to the preparation stage, in which the balance has shifted in the direction of change, there is a determination to change, and the actual steps taken are less tentative. For now, however, it is important to respect the patient’s ambivalence and support it if possible, recognizing that change is difficult and the costs and benefits of either choice [continuing or changing] are not clear to this patient.

A focus on the expected consequences of either continuing to drink or changing can help the person articulate needs and fears. Some of those expectations may be open to personal experimentation by the patient.

Supportive therapy or motivational interviewing [ Section 24 ] may help the person articulate more fully his/her drinking issues. However, too hard a press to take action could raise defenses or drive the person from treatment..

One or more family or couple sessions may be helpful in clarifying options, gauging the amount of family support for change, and helping family members tolerate the patient’s ambivalence. At the same time, you can work on the person’s other psychological issues and continue working on his/her awareness of the impact of drinking on his/her life.

PREPARATION

Here the balance has shifted, and the person is actively considering change and is making preparations and choices toward change, but hasn’t actually started; or he/sheis making small changes without a dedicated overall plan..

The short-term goal for this stage is to help the person move into the action stage by supporting these tentative beginnings and helping him/her expand on them. You can help him/her work on a plan for change, set a time table, explore specific aspects of the plan, and possibly experiment with some of the details. Some work can be done on the patient’s goals and expectations relative to drinking or not drinking.

A person in this stage is better helped to work on relatively small goals, easily achieved. The behavioral management part of treatment [ Section 25 ] can include specific personal experiments designed to identify and expand the limits of his/her control over drinking. The psychodynamic piece [ Section 37 ] involves examining the patient’s reactions to occasions when he/she drinks or doesn’t drink, along with the results of any specific experiments.

You can help the person develop a list of realistic change tactics, then help the person choose from the options available. This enhances the patient’s sense of self-efficacy [ Section 24 ]. (See also Miller, 2003, pp 143-144.)

When a patient is in this stage, it can be a good time to define more fully and completely the environmental pressures he/she may face in taking action, as well as his/her strengths and limitations in coping with them. Family and friends can be part of the process by providing support for change, helping define options, and reacting to the patient’s plans.

ACTION

In this stage, the person is aware of the need for change, has identified one or more goals, and is actively working toward them. A therapist’s job can include helping the patient be more specific about both goals and the means to achieve them, and to evaluate the effectiveness of actions taken.

The patient’s actions may or may not be successful in helping the person reduce or stop drinking. The important thing is that he/she is doing something toward the goal of reduced drinking or – preferably – abstinence.

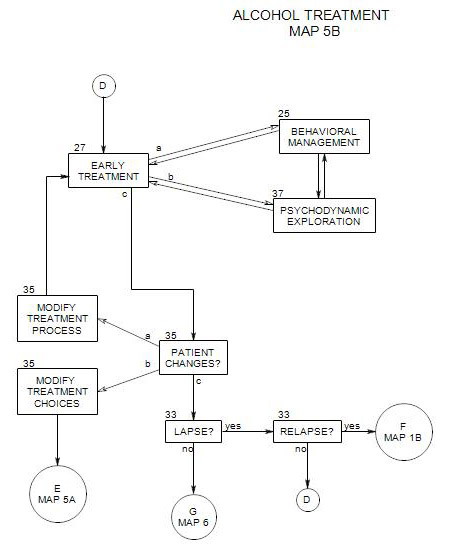

Early treatment with a patient in the action stage tends to be largely behavioral – taking whatever steps one can in order to bring drinking behavior under control. Section 25 discusses some techniques appropriate to working with a person in this stage. A psychodynamic perspective [ Section 37 ] can also be helpful by supporting behavioral change until the patient is stabilized – preferably in abstinence – and the symptom picture is clarified. If other psychological issues interfere with the patient’s ability to focus on alcohol management, or if the management part appears to be less consuming than expected, psychodynamic supportive treatment may help stabilize the patient and reduce relapse pressure from other areas of life.

Taking action may be far more difficult than it sounds. It involves actual changes in habits, thinking, and relationships. The patient may need a lot of help; and a re-visiting of adjunctive resources may be in order [ Section 19 ].

When a patient’s actions are successful, they can be reviewed in treatment, to facilitate incorporating them into the way he/she thinks or behaves. Failures can be seen as opportunities to re-evaluate the person’s behavior management, self-awareness, or both.

MAINTENANCE

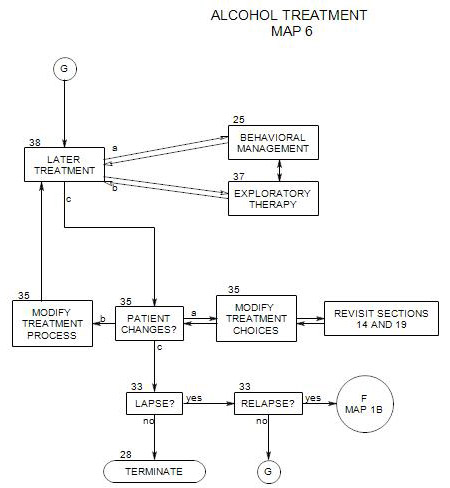

It is seldom clear when the action stage ends and the maintenance stage begins, and to some extent this separation is arbitrary. One rule of thumb states that maintenance begins six months after the first successful action of the action stage [Prochaska etal, 1992]. This is consistent with the idea that most relapses occur in the first six months of sobriety, and that change typically stabilizes in that time [Connors etal, 2001, p30].

The work here is different from the action stage and brings its own challenges. Whereas a person in the action stage can have specific goals, changes and time frames, the maintenance goal is to continue along a chosen path indefinitely. This is not to say that the person should remain the same and face the same issues. Over time, drinking should become less of an issue, cravings less frequent and intense, and life changes stable, more productive and more satisfying.

This raises issues of consistency in the face of temptation and threat, the security of the patient’s goals, and the effectiveness of the methods chosen to meet them. You can help by continuing to review the person’s goals and methods, and modifying the treatment as needed [See Section 35 ].

In early maintenance, behavioral management [ Section 25 ] is of major importance, with increasing opportunities for psychodynamic work [ Section 37 ] as time passes and behavioral control becomes consolidated.

A milestone comes when the person has been able to maintain sobriety for long enough – one to three months – that the diagnostic picture clears somewhat and there is greater opportunity to look at the patient’s psychological symptoms that are not the immediate consequence of drinking. At that point, it may be possible more clearly to identify psychological issues that are either independent of the person’s drinking or possible contributors to the urge to drink. If work has already started relative to those other issues, it can continue and possibly intensify.