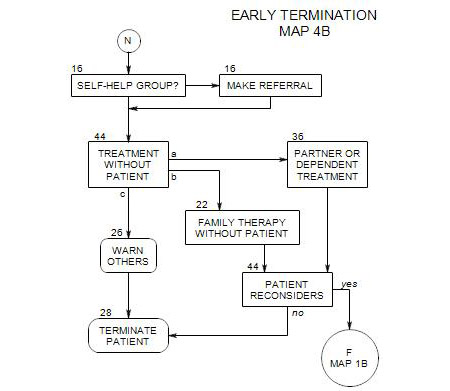

26. WARNING OTHERS OF DANGERS

- This section follows Section 6 when there are dangers the patient won’t deal with, or prior to termination for a patient who can’t be treated.

There are two general ways and times for involving a patient’s family and friends – either enlisting their cooperation in the patient’s treatment or informing them of risks posed by the patient. Section 21 is focused on the former and this section is directed toward the latter.

When you involve others cooperatively in the patient’s treatment, you generally want the patient’s full knowledge and consent. When the patient is a source of danger to others, you may not be able to get consent, and in some cases, you may not want to, or be able to inform your patient that others will be contacted.

It may be a good idea to inform the identified patient also under some circumstances.

26a. Danger to Others

As indicated in Section 21, there is disagreement among professionals about involving others in a patient’s treatment. Many therapists systematically avoid involvement with other people in the patient’s life. Other therapists argue that family and others should generally be involved in the treatment of alcoholic patients. Regardless of the theoretical or practical reasons for these positions, when the patient’s drinking is endangering him/herself or others, considerations of safety take precedence.

In these cases, you must consider abandoning neutrality relative to your patient’s life choices and helping to mobilize family, network or community resources to reduce the dangers to your patient and/or others affected by your patient. When this happens, the clearer you can be about the types of risk that concern you, the more effective your warning will be.

Contacting others may be required

when you become aware of serious dangers to them [ Section 6 ]

when treatment is disrupted [ Section 23 ]

before having an intervention [ Section 13 ]

around an early and risky termination [ Section 28 ]

This obligation needs to be balanced by the patient’s right to confidentiality and the possibility that others are already aware of the dangers to them.

There may also be legal requirements that you should be aware of, affecting one or both sides of the issue. These vary from state to state. You may be entitled to a legal consultation about these issues as part of your membership in a state or national professional organization or in connection with your professional liability insurance.

If your patient refuses to take appropriate action, you should also take into account the possibility that the patient will terminate psychotherapy in reaction to your involving others without his/her consent, and consider the advantages and disadvantages of both courses of action.

26b. Prior to Termination

If you are unable to work with a patient because of his/her physiological dependency on alcohol and the patient refuses to deal with the issue, continued work may be pointless and termination inevitable. There may also be implications of risk to the patient and others around him/her as a consequence of the termination. The patient may be about to binge drink, be at risk for drunk driving, be about to take legal or financial chances because of his/her drinking, etc. In this case, you may have a responsibility to inform others in the patient’s family that treatment is ending, so they will no longer be counting on you to help manage him/her.

26c. How to Involve Others

If you decide you must inform others, it is often best to discuss your proposed actions with your patient in advance, to inform him/her of what you plan to do, and try to obtain his/her agreement and help in doing it. This is important both for ethical reasons and for the patient’s sense of empowerment in decisions that affect his/her life.

If your patient won’t agree to involving others and you feel obligated to call them anyway, you should inform him/her of your plan and the reasons for doing so. It is possible, of course, that your patient’s reasons for not doing so are equally cogent- or more so- and you should reconsider your plan.

An exception to this principle occurs when you are planning a surprise intervention [ Section 13 ], where the patient probably wouldn’t come to the session if s/he knew what was about to happen, and where the power of the meeting comes in part from the element of surprise.

Reconsider this in the light of non-surprise interventions

Giving notice to others may also provide an incentive for family and friends to take a more active role in helping the patient realize a need to change, and possibly lead to a re-entry into treatment at a later date.

26d. Keeping Records

Any time that you discuss contacting others with your patient, you should record your discussion and your patient’s reaction in the non-notes section of his/her record, so that you can refer to it later on if necessary, without having to disclose your own therapy notes. Indicate that the discussion took place, when and under what circumstances, and how it was resolved.