23. DISRUPTION OF TREATMENT

- This section follows Section 27 On Map 4.

Treatment may be disrupted in different ways; but whatever the cause, the disruption must be dealt with in some way. Otherwise, the treatment may be in jeopardy, with a possibility of negative consequences for the patient.

23a. External Disruptions

Many kinds of outside changes can disrupt treatment, including changes in the therapist’s life, changes in the patient’s life, changes in the treatment situation, changes in the patient’s insurance coverage, and so on. Patients will sometimes assume that a disruption means the end of treatment, without checking with the therapist first.

Any such disruption should be dealt with quickly and directly. For insurance and fee problems, a new fee arrangement can be negotiated. A change in the patient’s work or living situation may require adjustments in frequency of sessions, times of sessions, use of the telephone, or other aspects of the relationship.

Once practical matters have been deal with, it may be necessary to deal with the impact of the change on the treatment, at least to the extent that the mode is exploratory.

23b. Disruptions Internal to the Patient or the Treatment

This category can include attitudes and reactions of the patient that interfere with the effectiveness of treatment in some way.

A patient may act out, by –

- arriving late.

- missing sessions.

- making excuses not to schedule future sessions.

- cancelling sessions.

- disappearing.

He/she may arrive for sessions intoxicated, in which case the session may have very little impact on his/her thinking or behavior; or he/she may go out drinking after the session, undoing or forgetting any work that was done. If this happens, he/she is already having a relapse and should be handled accordingly [See Section 33 ].

Defensive reactions may increase [See Section 34 ]. Often it involves some form of denial, together with behavior or attitudes that render treatment ineffective. A patient may refuse to discuss his/her drinking, possibly becoming angry and leaving the session if the therapist persists. Other defenses may also be called into play, making treatment more difficult, less effective, or impossible.

Normally, these are the bread and butter of exploratory psychotherapy – whatever the patient does has meaning and that meaning can be examined. Change can be the signal for either growth or regression, which can form the basis for new psychotherapeutic work. However, when these reactions can’t be addressed effectively [as when the person simply disappears from treatment], the question arises as to what can be done to salvage the work, or whether it can be salvaged.

23c. Modifying the Treatment

A number of possibilities are open to the therapist for dealing with disruptions, including

- direct confrontations with the patient

- greater focus on the patient’s defensive operations

- involving other family members

- re-evaluating the patient’s stage of change

- re-evaluating level of care

- terminating the patient

Direct confrontations occur within the context of ongoing psychotherapy, and involve continued focusing of attention on the current issue, whether it be the patient’s drinking or some other form of acting out, and its consequences to him/herself and to others.

Defenses may need to be handled if they interfere with treatment process. This is discussed in Section 34.

Other family members may be involved by bringing them into the patient’s sessions, having family sessions, getting them into their own treatments, or helping them get involved in support groups such as Al-anon or Al-a-teen [See Involving Others, Section 21 ]

An error in gauging the patient’s stage of change could have led to inappropriate treatment, and the patient could be reacting to that. Or the patient could have moved to another stage and the former interventions no longer are effective.

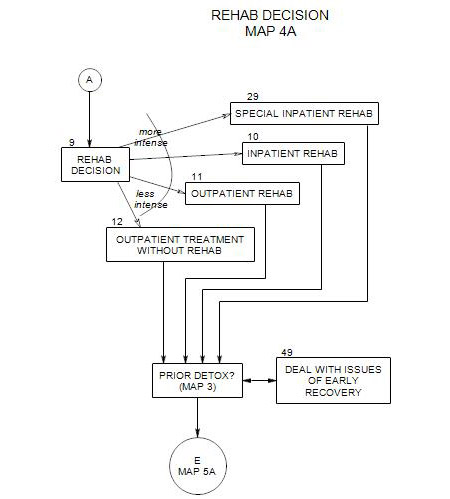

If individual outpatient psychotherapy is ineffective because of the patient’s drinking, perhaps some form of rehabilitation should be considered [See Level of Care Decision, Section 9 ]. If the patient is also misusing other substances (marijuana, cocaine, etc.), then a drug program may be the most effective choice for him/her [see Section 29 ].

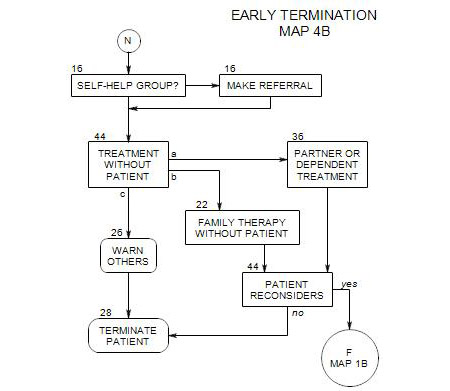

23d. Terminating the Patient

If the patient refuses to consider modifications of treatment, you may need to terminate, [ Section 28 ] to preserve the value of therapy and/or to send a clear message to the patient that his/her alcohol misusemust be addressed before anything else can happen. On the other hand, the patient may already have terminated with you, by disappearing entirely – moving, changing telephones and not letting you know, etc.

If you think that the patient’s termination will lead to increased risks for others, then you may also have an obligation to warn them at this time [See Section 26 ].

Note that if you should become more involved in a patient’s life and with significant others as a consequence of the judgment of danger, your previous psychotherapeutic relationship with the patient may be compromised [if it isn’t compromised already]. Then, if the patient is willing to continue at all, it may have to be with a different therapist.