SECTIONS: 5 | 8 | 16 | 19 | 21 | 22 | 24 | 25 | 39 | 44 | 46 | 47 | 48

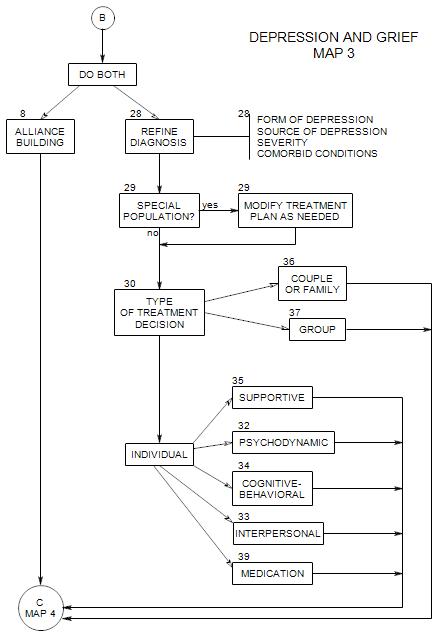

SECTIONS: 8 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 39

-

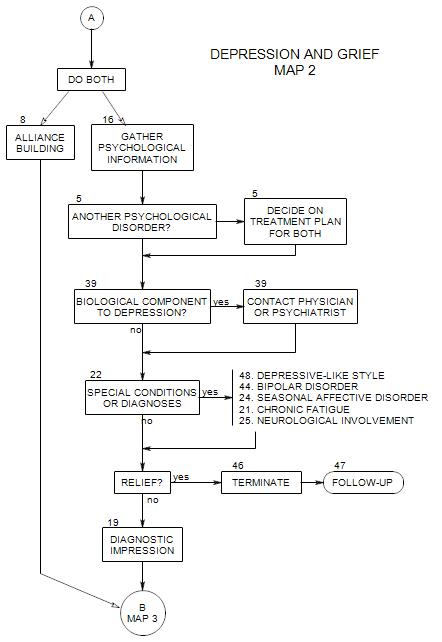

This section appears at the top of Map 2, when you have decided on outpatient psychotherapy and have already considered medical sources of depression.

In this section we consider aspects to the person’s life that could lead to depression or affect the strength of a person’s depressive reaction.

Any major life change [even a positive change] can contribute to a person’s stress and increase the chances of a depressive reaction; so it is useful to ask about all areas of the person’s life.

Patients may not be aware of factors that actually contribute to their depression; or they may be reluctant to discuss them. You may have to be clear, direct, detailed, and persistent in your questioning. You may have to ask some questions more than once.

Keep track of all possible sources of depression. There is a good chance that the patient is dealing with more than one reason to be depressed. Plan to find out as much as possible about each of them.

At this point, we have already considered diseases, disability and medications as primary sources of the patient’s depression. If this has led to discovery of a primary source, then psychological exploration can either search for additional sources [such as a family’s mistreatment of a handicapped person] or the patient’s difficulties in accepting or managing the consequences of a medical problem. If the medical search has not turned up definitive causes of depression, we will be looking for the origins in psychological issues.

At this point, if we determine that the person’s depression is rooted in misinterpretations of his/her life, we emphasize psychotherapy; and if we think that there are serious interpersonal issues, we focus on interpersonal treatments.

16a. Phenomenology

Ask about the patient’s experience of his/her depression: how strong it is, whether it varies at different times of the day, the week, the month, or the year. Find out how debilitating it is, and its effect on the patient’s life

Does the patient experience the depression as long-standing, or of relatively recent origin? Is there a sense that it is temporary or permanent?

Does the patient feel responsible for his/her depression? Is the patient reacting to external events, or does it seem more that he/she is the cause of his/her own problems? The old endogenous-reactive distinction may have meaning in the patient’s experience.

Ask about body sensations related to it [This can lead to greater self-awareness, possibly including associations that will direct you to sources of the patient’s depression]:

- “Where do you feel it?”

- “What does it feel like?”

- “Does it change? When and how?”

- “Do you feel it right now?”

Ask about impulses connected to it:

- “What are they?”; “Have you ever acted on them?” While it may be valuable to leave the initial inquiry open, you will especially be concerned about impulses to hurt the patient’s self or others

Ask about other symptoms that might be connected to it:

- anxiety [depression may be secondary to, and a consequence of, prolonged anxiety; or anxiety may develop out of depression.]

- confusion, poor organization, poor concentration [which can be either causes of depression (awareness of loss of function) and secondary to some other process, or a consequence of depression.]

- hallucinations [if a psychotic process is the source of the patient’s depression].

If there have been more than one depressive episode, ask how long a period of depression usually lasts, and how long a period of time occurs between successive episodes. This can lead to a better understanding of triggers for a depressive reaction; or if the depression is recurrent, it may lead to a schedule that helps predict the next episode.

16b. Immediate Antecedents

If there is variation in the patient’s experience of depression, ask if there are particular thoughts, events or settings that seem to trigger it or be associated with it.

16c. Current Life

It’s helpful to gather information on any current, ongoing pressures that could lead the person to be depressed, including recent life changes, family pressures, relationships with family members, and other sources of interpersonal discomfort. [See Section 18 for more on this.]

It’s also helpful to find out about the person’s sources of interpersonal support, especially if there may be a need for help or monitoring. [ also in Section 18. ]

16d. History

HISTORY OF THIS EPISODE

Ask how long the patient has felt this way, if he/she can identify a beginning to it.

Ask when it started, and the patient’s theory about what led up to it.

- This can help identify grief, medication reactions, hormonal changes, traumatic events, or other sources of the feelings.

CAUSES

Depression is often a response to a stressful situation or event. Various types of depression have been identified, according to the kinds of precipitating stress. These may include changes in the environment, trauma, losses, change of season, physical changes, use of drugs, etc. We will come back to these precipitants later.

Look for multiple antecedents to the present episode. Many people will be able to cope with a major stressor without help but collapse when additional problems arise. [For example, a person might get by with a bad marriage and work stress, then collapse into depression at hearing an unfavorable medical diagnosis. All three sources may need to be examined.]

PRIOR EPISODES

Ask about previous depressive episodes, including any in childhood, and what they seemed to be related to. Ask how previous episodes were treated, or what brought them to an end.

- This gives more information on vulnerabilities, personality components of depression and ideas for treatment.

- It also affects the choice of medication, if it is used. Some antidepressants can precipitate a first manic episode and change the diagnosis.

MANIC EPISODES

Ask if the patient also experiences periods of heightened interest, energy and activity [that could suggest mania or hypomania].

Typical lists of manic symptoms include…

- racing thoughts.

- pressured speech.

- inflated self-esteem or grandiosity.

- decreased need for sleep.

- physical agitation, or working more, or increased sexual activity.

- distractibility.

- poor judgment.

16e. Recent [Positive and Negative] Life Changes

Any change can lead to increased stress and exacerbate depression: births, deaths, change of…

- job.

- Education.

- marital status.

- family constitution, etc.

16f. Family Pressures

Ongoing conditions in the patient’s family can have a long-range effect on his/her mood. Ask open-ended questions, first about living arrangements and family, then about any quality of home life that could lead to frustration, fear, sadness, etc. Sources of pressure could include…

- living arrangements, lack of privacy, etc.

- obligations.

- financial issues, possible deprivation, arguments over money, a need to work two jobs, etc.

- educational limits.

- battering, or other forms of physical, verbal or sexual abuse.

- caretaking of others and consequent lack of personal freedom.

- bickering among family members, that the person manages.

- loss of a family member through death, estrangement, moving away, etc.

RELATIONSHIPS WITH OTHER FAMILY MEMBERS

When a person feels very different from other family members or is otherwise emotionally isolated from them, depressive symptoms may be exacerbated. For example, a gay person might hide his/her sexual orientation from parents and siblings, and not feel comfortable confiding in them about feelings that they might not understand. Similar problems may arise in friendships, choice of lovers and work relationships.

A person’s family may also be a major source of support, helping him/her deal with depression, and keeping it from developing into something worse. In this case, it is important to ask who is especially helpful and how.

16g. Attempts to Control or Manage Depression Individually

If it hasn’t already come out in history-taking, ask what the patient has done to try to manage the depression, during the current or any previous episodes. This can give you a lot of information about effective and ineffective treatments. It can also tell you about the person’s style [active or passive]. It may uncover substance abuse or other conditions that need treatment along with the depression.

More specifically, ask about:

- prescription medications the person may be taking, and for what

- over-the-counter medications, and for what

- health foods, and reasons for them

- exercise: types, frequencies, and amounts

- alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, or other ‘recreational’ drugs: which ones, how often, how much

Generally, open-ended questioning is most useful, because you can’t predict what about the person’s life may be affecting his/her mood.

16h. Social Support

Ask about friends. Depressed people tend to have fewer friends than other people, and to see their friends less often. They are more likely to say that their friends are far away or dead.

Relationships may be unsatisfying, filled with conflict, arguments, and withdrawal.

On the other hand, the patient may have one or more friends who are available and supportive. Find out who they are and what they do to help the person get through periods of depression. Ask if the person can rely on them more or be more involved with them.

Group membership can also be valuable in managing depression, if the person makes use of the group. This can include groups for depressed people, or activity groups that give the person purpose and involvement: political groups, social groups [like Sunday afternoon pro football at Randy’s] church groups, adult leadership in the patient’s child’s activities, and so on.

16i. Personal and Family History

The patient’s family of origin can be a source of tension and/or a resource for managing the patient’s issues.

- Get a family tree that includes all current and significant deceased members, and shows something of their relationships with each other.

- Ask about family experiences and activities.

- Find out about the living conditions of significant family members. The patient may be caught up in the despair of others.

- Ask about family members with emotional disturbances or substance abuse.

- Family members can also be major resources for a depressed person. Ask whom the person is close with, and how others in the family can be helpful with the person’s moods.

If the person is an adult with a family of his/her own, ask about them and their impact on his/her moods.

- A spouse can be helpful, or contributory to the person’s difficulties.

- The children of parents who are depressed or in conflict often have issues of their own, and can exacerbate the difficulties of an already depressed person.

- Other children may become more considerate when a parent is sad, and that can be very supportive.

- There may be extended family in the person’s home [a parent, sister, cousin, child of a brother, etc.] increasing stress and a sense of overwhelming responsibility.

The patient’s life history is often implicated in depression. You can gather some initial information about early life, but a lot of important facts are likely to become evident in the course of treatment. Ask about…

- childhood experiences [esp: early separations, losses].

- any history of emotional difficulties [depression, anxiety, substance abuse].

- any history of physical, emotional or sexual abuse, by adults, siblings, neighbors, etc..

- expectations placed on the patient, possibly responsibilities and demands that couldn’t be met.

- generally, what the person was like before depressed, and in what ways he/she was different then from now.

With different populations of patients, you may need to look for different sources of depression. Your choice of what to look for will depend on what you know about the population[s] that the patient seems to belong to.

For example, some pressures are typically different for women and men.

- Women may be faced with cultural beliefs that women should be passive and dependent, leading to a sense of learned helplessness.

- A depressed woman may be more vulnerable to anorexia or bulimia.

- A depressed woman is more likely to have a history of sexual abuse.

- A depressed man is more likely to act out with irritability, violence, etc.

At the same time, you need to be careful not to lead the patient to believe that you want him/her to report certain kinds of thoughts or experiences. To do so might inadvertently give the impression that other issues are unimportant; and for this patient, one or more of the other issues could be critical. You need to give the patient permission to talk about whatever he/she needs to, yet not direct the flow of the patient’s narrative.

16j. Interpersonal discomfort

Ask about comfort in social relationships. Depressed people may be ineffective with other people, and feel awkward and inept. They may…

- speak slowly.

- have a monotonous tone of voice.

- seem angry to others.

- avoid eye contact.

- be uncomfortable trying to express themselves.

- talk too much about their own discomfort and difficulties.

- judge themselves harshly.

- have difficulty making eye contact.

16k. Prior Psychotherapy

It is helpful to explore a patient’s previous experience with psychotherapy, for a variety of reasons [see also “New Patient”, Section 6]:

- ―to know what kinds of problems the patient had in the past [especially: other depressions, bipolar disorder, substance abuse].

- ―to find out how previous issues were handled, and with what success.

- ―to learn the patient’s expectations of therapy and the therapist.