SECTIONS: 5 | 8 | 16 | 19 | 21 | 22 | 24 | 25 | 39 | 44 | 46 | 47 | 48

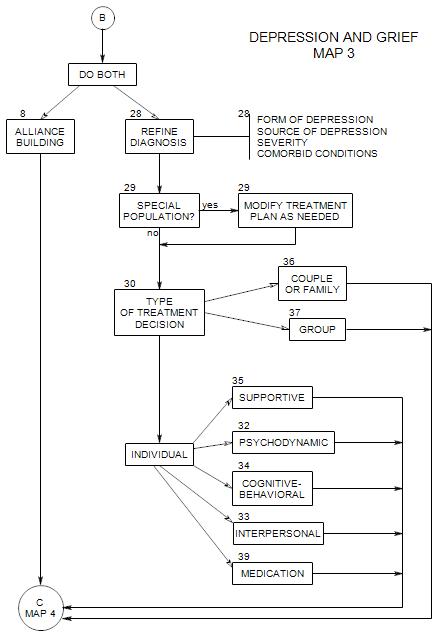

SECTIONS: 8 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 39

-

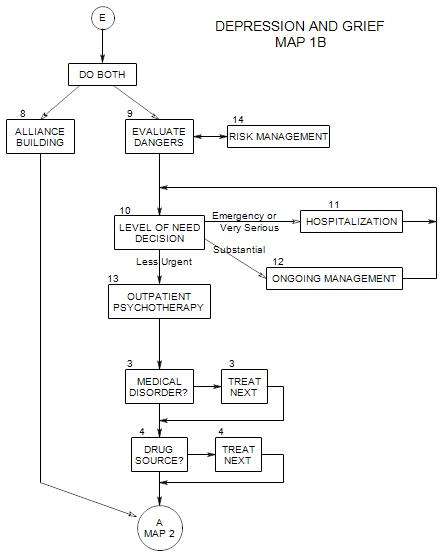

This follows Section 2 on Map 1B

In this section, we first discuss kinds of dangers, then consider degree of danger and its effect on the treatment choices.

9a. Kinds of Dangers

The major danger that we are concerned about is lethality: danger that the patient will suicide, hurt him/herself, or hurt others out of despair or anger.

Danger of lethality may be suggested by

- Strong negative emotions: rage, hopelessness, despair, guilt.

- thoughts of death as revenge, rebirth, getting even, self-punishment, atonement for sins, reunion with someone deceased.

- idea of using one’s death to express strong feelings or to control others, e.g.: by inducing guilt.

- difficulty communicating in less extreme ways.

To evaluate lethality,

- ask directly: “Are you likely to hurt yourself?”; or ask questions about suicidal or homicidal thoughts: “Have you ever considered suicide?”, and follow up with questions about the extent of fantasy, planning and preparation. Be careful not to lead the patient or appear to be suggesting suicide as an answer.

- ask whether the patient has ever tried suicide in the past. If so, find out about it, and whether circumstances are similar in any way, etc. Prior attempts generally suggest greater risk.

- ask if anyone else in the person’s life has committed or attempted suicide, and if so, ask about the patient’s reactions. [This is perhaps more important for an adolescent than an adult.]

- determine whether the patient is accurately oriented and not psychotic.

- ask about comorbid conditions that could exacerbate the depression: substance abuse, obsessive-compulsive disorder, etc.

- make your own judgment about comorbid conditions, esp: impulsivity or relatedness.

Ask how the patient manages his/her depression. Some attempts to self medicate may introduce additional dangers, e.g.: risk-taking or using alcohol. Others, like eating or shopping, may have uncomfortable long range consequences that lead to erosion of self esteem.

Information from family members can affect your judgment of the risk of suicide. Many of the above questions can also be asked of family members. If the patient is impulsive, then excessive risk-taking may be a sign of suicidality.

If the patient is more deliberate and planful, then signs of depression can include

- neglect of self.

- increased interest in religion, or withdrawal from religion.

- talk of the wish to die, including comments about others being better off.

- increased interest in “putting things in order”, which can include giving away possessions.

Assessing mental status is important, because mental status affects the probability that the patient will behave in a predictable way. A cautious approach is to assume that an unpredictable patient is more likely to be at risk.

Assess short-term memory. Depression can affect a person’s ability to remember information and accurately report it. A brief test could be to give the person something to remember at the start of the session, ask about it later on.

Look for delusions, which might suggest a psychotic process: that life is hopeless because his/her water is being poisoned; or that he/she is destined from birth to fail at everything; etc. However, asking directly may threaten the person and scare him/her away from treatment.

You may want to ask –carefully- about hallucinations: did the person ever see things that no one else saw, or that clearly weren’t there? What was his/her reaction? How did he/she cope with it? Or: has the person ever heard voices telling him/her to do something? Could he/she make the voice go away? etc.

Notice the patient’s level of cognitive functioning: vocabulary, abstract reasoning ability, etc.

Other dangers to consider are

- discouragement: the patient’s belief that he/she can’t be helped, and possibly not returning for further treatment

- alienation of support, when the patient’s family or friends have stopped helping or started blaming; when the patient starts to feel ashamed and separate from others

- loss of job through failure to carry out responsibilities

- medical risks, due to disease or inappropriate medications, and where the patient would benefit from a medical consultation

- risks to health or safety, out of the patient’s failure to take adequate care of him/herself [not eating, not taking necessary medications, ignoring safety precautions, etc.]

- use of alcohol or other drugs to self-medicate [ cf: Section 4 ]. Changes in use.

- risks to others, especially the lives or safety of children or other dependents through failure to attend to or care for them adequately

Of these, dangers to life and safety must be considered first, but the others are also very important. For example, a patient who is too depressed to go to work may lose the job, become more depressed, and enter a vicious spiral of increasing failure and depression.

Also consider the patient’s felt need for help and level of subjective discomfort.

9b. Amount of Risk and Treatment Response

RISK IS RELATIVELY SMALL

When the risk is small, you may decide to begin on a regular schedule immediately, and simply schedule the next appointment. Ordinarily, these days, we assume weekly sessions, though of course there are many factors affecting session frequency.

RISK IS MODERATE

For moderate risk, you might want to offer the patient one or more of the following:

- calls between sessions, for reassurance, support, advice, interpretation, etc.

- more frequent sessions [ see Section14B ], possibly two or three per week. You might defer deciding on the number of sessions per week but because of the severity of the patient’s depression, offer to see him/her again the next day.

- Involving family or friends [ see Section14E ] can take a variety of forms and be helpful in many ways.

RISK IS GREAT

If the patient appears to be at risk for suicide or other dangerous behaviors, then more serious interventions may be called-for:

- you might ask whether he/she can contract with you [ see Section14A ] not to suicide before the next scheduled session.

- A contract could include a provision to call you or someone else if the risk seems great.

- You may also give the patient the number of another therapist or of local suicide hot-lines [ see Section14C ] to call if he/she feels at risk and is unable to reach you.

- You can also discuss the possibility of going to a hospital emergency room [ see Section14D ] if the patient is unable to reach you or deal with the depression without you.

- If the patient is unable to contract not to suicide, then you may have to insist on hospitalization [ Section 11 ], and possibly even call the police to escort the patient there.

PATIENT’S JUDGMENT IS COMPROMISED

- Means: possible psychotic process.

- Increases the possibility that hospitalization will be necessary, and suggests consulting with a psychologist or psychiatrist who has admitting privileges at a hospital the patient might need to go to.

- See Section 11.

9c. Medical Attention

If you discover that the patient has a medical condition that requires immediate attention, whether or not it seems directly related to the patient’s depression, ask the patient to see his/her physician or go to a hospital emergency room.

Reference: Hendin (1991)