-

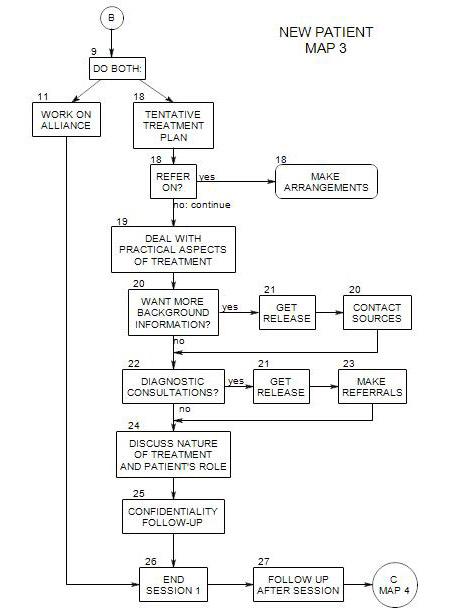

Follows Section 9 on Map 2

Coordinates with Section 10

An alliance is a sense that you and your patient are both working for a common purpose and can help each other do your respective jobs. An alliance not only helps by facilitating the diagnostic and treatment work; it is also part of the treatment, by giving the patient a sense of not being alone, of being able to talk openly and express feelings.

Note that we have split the discussions of asking about symptoms and working on the alliance into Sections 6 and 8 for conceptual clarity, but that you must deal with both together. Also note that, although we have shown these two issues to be part of the first session, they clearly will continue into later sessions as well.

You can help the patient feel comfortable, secure, and able to talk with you in a variety of ways, including the following, some of which are also discussed in Section 10:

1. Ask questions that lead the patient to say what he/she wants to say. Early on, this could include his/her experience of the symptoms, his/her theories about the reasons for having them, and other people’s reactions to them.

2. Ask questions that the patient hasn’t thought of but that seem important and related to the problem once he/she does think about them. This could include-

- specific symptoms, such as mood cycles, changes in sleeping or eating patterns, etc.

- physical aspects of his/her symptoms.

- when the symptoms started, and what else was happening in the patient’s life around that time.

- why the patient is here right now: what changed recently that led to this appointment

- what the patient has done to treat the problem.

- how the patient thinks you can help; or what the patient wants from you.

This is not only information-gathering; it is also one of the early phases of treatment. By asking questions, you help the patient re-frame the experience of his/her symptoms, and re-evaluate their presumed causes.

As in any encounter, your attitude and tone convey as much as – or mor than – your words. If you are respectful, concerned and caring, your questions are more likely to be heard as supportive, and you can encourage the patient to greater exploration. If you are heard as challenging, critical or suspicious, a patient sill be more likely to experience you as dangerous and tempted to withhold or distort responses.

3. Respect resistances. Be very careful about pushing for feelings, underlying motivations, etc. Many people, especially those without prior psychotherapy experience, will experience this as intrusive and inappropriate or frightening. The same is even more true for the use of the analytic interpretation or anything similar to it. For example, if a patient identifies a conflict area but doesn’t want to discuss it, you could suggest he/she may want to come back to it when he/she feels more comfortable with you.

4. Give the patient information about your plan or way of working and what to expect. How much you say will depend on your approach and your sense of the patient’s need to know.

It could include ideas that-

- talking can help a person feel better;

- you won’t be able to tell the patient a lot the first session because you need to learn about him/her first

- he/she needs to decide in a first session only whether he/she feels comfortable with you and is able to talk reasonably easily, and whether you seem to listen and understand.

5. Give the patient some information about these symptoms or others with similar symptoms. This can normalize the patient’s situation, offer hope, and be reassuring. It can also show the patient that you are knowledgeable and sympathetic. Under these circumstances, talking about his/her variation of a relatively common problem will be more likely to seem like an exercise with potential for constructive change.

6. Consider giving the patient a homework assignment, possibly to explore and keep track of-

- mood as a function of time of day.

- antecedents of symptoms, as they occur during the time between sessions.

- ―thoughts related to the symptoms.

- thoughts when the person is experiencing his/her symptoms.

- dreams.

- other feelings, especially anger, anxiety, depression.

7. One dimension of process is the extent to which you should make various treatment decisions alone or in consultation with your patient. Issues could include the patient’s need-

- ―to be taken care of and reassured.

- ―for self-expression.

- ―for control over his/her own life.