-

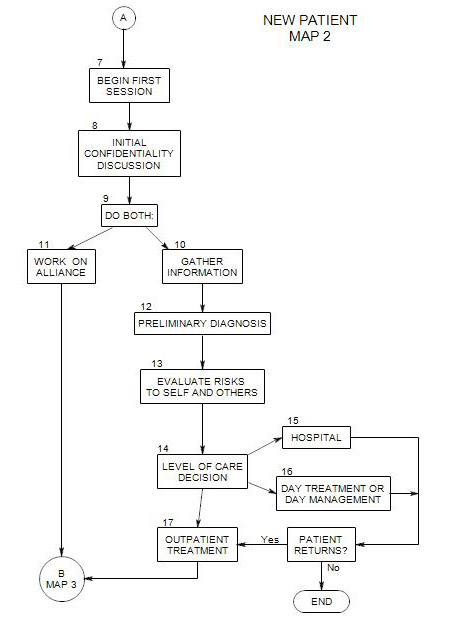

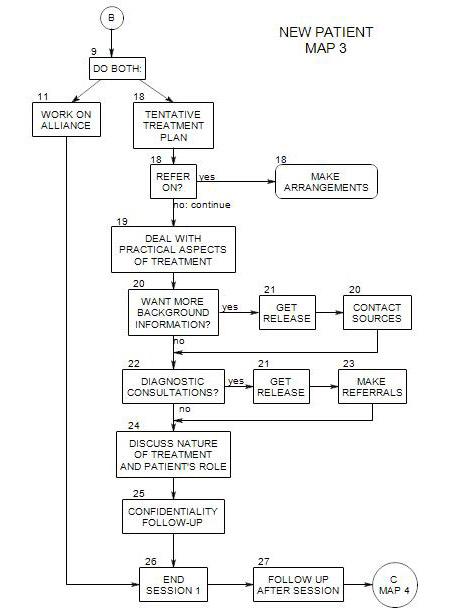

Follows from Section 9 on Map 2

Coordinates with Section 11

You must pursue the information that you think will help to get the treatment started most effectively. You have very limited time in the first session, and the way that the session goes will determine whether the patient continues, and if so, whether he/she continues with you.

Note that this discussion splits the aspects of asking about symptoms and working on the alliance into Section 10 and Section 11 for conceptual clarity, but that you must deal with both together. Also note that, although these two issues are treated here as part of the first session, they clearly will continue into later sessions as well.

10a Process of Information Gathering

This section calls for you to gather a lot of information, too much for one session. You must of course be selective, and gather what you can in whatever order you can. In general, following a checklist or other formal sequence of questions can interfere with the patient’s freedom to tell his/her story. It can also put a barrier in the way of establishing a treatment alliance by making it appear that you are more interested in dealing with your issues.

Reviewing the first session can lead to topics you can raise in subsequent sessions, to fill out the picture of the patient’s life and issues.

As is suggested in the topic maps and Section 18 of this map, you may need to continue this phase for several sessions; and in some sense the process continues throughout treatment. For now, the idea is to learn enough to be able to move on as effectively as possible.

10b General Information

Your main job at this point is to understand the patient and what is leading to the patient’s symptoms.

To get started, you can ask why the patient came to you. Typically it consists of a list of physical and/or emotional complaints, complaints about the patient’s family or living situation, work, etc. The patient may need help with this, especially in expanding the list of complaints and symptoms, and in seeing consistencies in various aspects of the list.

This can be a lengthy process, and you may want to move away to other issues after a while and re-visit it in a later session.

Other possible topics are:

- What about the patient’s symptoms led to treatment? [gives information on severity of distress or patient’s symptom tolerance]

- Why now, and not a month ago? What changed? [can lead to discussion of severity of symptoms, changes in symptoms, change in life, or change in the patient’s impact on others]

- Was the patient pressured or coerced to come? [may give information on denial of symptom importance, conscious resistance to awareness of the symptom or its consequences or the patient’s interpersonal relationships]

- Why you and not another therapist? This is especially interesting if the patient was in prior treatment [It may reflect rejection, disappointments, prior success or failure of treatment, a move from somewhere else, other changes in the patient’s life, unavailability of the previous therapist, etc.].

- Who recommended you and what did he/she say about you [This can give information on the patient’s expectations.] Why did the patient ask that person?

You need to-

- identify and evaluate the patient’s presenting problems.

- make a preliminary inference about underlying pathology [ Section 12 ].

- decide on a level of care [ Section 14 ].

- gather some practical information.

- begin the treatment process. This, of course, has already begun.

At the beginning of any treatment, you can expect a patient to be especially anxious about the process and the possible outcomes of treatment. This can be a good time to observe at least some of the patient’s defenses.

Try to determine just what the patient’s symptoms and issues are, ideally in the person’s own words, and from his/her perspective. If you are unclear, you can wait, ask a question, or rephrase and ask if you are right.

Ask what the patient wants and expects from therapy. There is a reason that he/she came to you at this time. What is it? How can you help?

Some people present risks to themselves and others. You need to find out what risks this patient presents with, and how great those risks are. This is discussed further in Section 13.

Work on the patient’s alliance with you, and with treatment [ Section 11 ]. Treatment is a collaborative effort, and the patient has an active role. Help him/her begin to define it.

Gather some basic information: age, ethnicity, whom the person is living with, friends, other family. This has many implications: pressures and responsibilities, sources of support, the patient’s view of life as conditioned by family living, etc.

Ask about the patient’s life situation, especially stressors, changes, responsibilities and demands on him/her. General categories include work, recreation, and how leisure time is spent. This last category can include participation in groups and activities.

Try to learn something about the patient’s childhood and family of origin. Often current issues have their origins in the person’s early life, through ongoing habits, expectations, values, etc. The person may or may not be aware of the connections. The extent to which you pursue this line of information will be affected by the extent that you and the patient think his/her current symptoms and issues have roots in early learning and experiences.

Ask about physical symptoms that may bear on the psychological symptoms, either as causes or consequents [sleep, weight gain or loss, disabilities, etc.] People with sleep problems or chronic pain may have depressed, difficulty focusing, irritability and temptation to find relief in alcohol or drugs.

Ask about physical history, especially traumas, deprivations, drug use, illness, living in other cultures, etc., and their effect on present feelings, interpretations of events, expectations, etc.

Find out about drug use: prescriptions and what they are for; over-the-counter medications; recreational drugs; caffeine and tobacco use.

Try to guess what the person is leaving out, and in what way the perspective you are hearing is distorted.

- Some people try to present themselves in as good a light as possible, and omit their own part in conflicts and issues. They don’t want you to help them change; they want you to change the people and situations around them.

- Some may present themselves in a particularly bad light, to get your sympathy or to encourage you to help them.

- Some will leave out information because they won’t know that it’s relevant

- Some will go on and on with information that’s clearly digressive or reflects some theory they have about what’s wrong.

- Some may just be confused.

Ask about attitudes and expectations, of self, others.

Ask about religion, family mores and values. Often conflicts with others reflect conflicting values and expectations [eg: He is so withholding: he never tells me what he thinks or feels. vs She’s so selfish – always talking about what she is thinking and feeling and never asking about me.]

10c. Phenomenology

Ask about the patient’s experience of his/her symptoms: how strong they are, whether they vary at different times of the day, the week, the month, or the year. Find out how disturbing and debilitating they are, and their effects on the patient’s life.

Ask about body sensations related to any psychological complaint

- Where do you feel it?

- Does it change? When and how?

- Do you feel it right now?

Ask about impulses connected to it:

- How do you deal with it? Is there anything you need to do when you feel that?; Have you ever acted on your impulses, when you felt the urge?

Ask about thoughts associated with it the symptoms: explanations, causes, etc.

Ask about other symptoms that might be connected to it:

10d. Immediate Antecedents

If there is variation in the patient’s symptoms, ask if there are particular thoughts, events or settings that seem to trigger them or be associated with them.

Is the patient reacting to external events, or are the symptoms internally generated?

10e. History of Presenting Issue

Ask how long the patient has felt this way, if he/she can identify a beginning to it. If he/she can identify a start date, it may lead to a theory about its origins – or the patient may relate a theory that he/she already holds about it.

Look for multiple antecedents to the present episode. Many people will try to cope with a major stressor without help but collapse when additional problems arise. [For example, a person might get by with a cold and distant marriage and work stress, then collapse into depression at hearing an unfavorable medical diagnosis. All three sources may need to be examined.] Ask about previous episodes, including any in childhood, and what they seemed to be related to. Ask how previous episodes were treated, or what brought them to an end.

10f Attempts to Control or Manage Symptoms

Ask what the patient has done to try to manage his/her symptoms, during the current or any previous episodes. This can give you a lot of information about effective and ineffective treatments. It can also tell you about the person’s style [active or passive]. It may uncover substance abuse or other conditions that also need treatment. [for example, a depressed person may drink more and more coffee to feel better, exacerbating the depression.]

More specifically, ask about-

- prescription medications the person uses, and his/her reasons for using them.

- over-the-counter medications, and reasons for using them.

- health foods, and reasons for them.

- exercise: types, frequencies, and amounts.

- alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, or other ‘recreational’ drugs: which, how often, how much.

- caffein in all its forms: coffee, tea, soft drinks, etc.

- self-help groups

- relaxation, meditation and yoga

For each way of managing symptoms, ask when, why and whether it helped.

10g. Prior Psychotherapy

It is helpful to find out the patient’s previous experience with psychotherapy, for a variety of reasons:

- to know what kinds of problems the patient had in the past, how they were handled, and with what success.

- to determine the patient’s level of sophistication with regard to treatment.

- to learn the patient’s expectations of therapy and you as therapist.

If he/she had prior therapy, ask, for each treatment experience,

- what kind of treatment it was, for how long it lasted, how frequent

- reason for it, and how and why it ended.

- how effective it was

- with whom. Also ask, why not return to that person? etc.

10h Observations of Patient in Session

Usually this is an informal process, of observing things about the person that could have relevance to his/her current difficulties.

A common formalization of this process is called the Mental Status Examination. This consists of a list of observable characteristics that could be signs of underlying disorders.

Typically you review this list after the session and make note of any of the listed characteristics that could be related to the person’s complaints or your current diagnostic understanding of him/her. Observations that don’t appear to be related to the person’s complaints should also be noted and reviewed later for their possible consequences to the person.

10i. Reactions to Patient

Keep track of your reactions to the patient. They may give you clues to diagnosis that you may otherwise not be able to put into words. Some reactions may be induced by the patient, who needs you to be loving, punitive, cold, etc. They may also be predictive of your ability to help this person [It’s harder to help people you don’t like, don’t trust, etc.]

10j Some Practical Issues

These need to be addressed, often in the first session. Misunderstandings about the treatment frame can undermine the treatment. These issues are addressed in other sections:

- the financial arrangements: fee, method and time of payment, whether there is insurance coverage. Whether the person is in a managed care program, and procedures for obtaining coverage. [ Section 19 ]

- the patient’s time availability and whether it matches yours [ Section 19 ]

- confidentiality issues [ Section 8 on Map 2 and Section 25 on Map 3]

- the pros and cons of contacting others regarding the person [ Section 20 ]

References:

Lucas, Susan: Where to Start and What to Ask; An Assessment Handbook. New York: W.W.Norton, 1993, Ch. 1.