SECTIONS: 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 19 | 24

- Follows from Section 14 on Map 2

Agoraphobia typically consists of fears of being in specific places, of being out in the world, of leaving home, of being alone, or of being trapped. The person commonly avoids the feared situation or circumstance in some way [by staying home, for example, or by going out only in the company of others]. In most cases, the fears and avoidances are generalizations from panic attacks, though not necessarily. For this reason, it is common to describe agoraphobia with panic attacks as separate from agoraphobia without panic attacks.

21a. What’s Avoided

External Cues

People with agoraphobia often avoid a range of places and situations, which have in common that the person might feel trapped – that escape might be difficult or blocked. Typical situations avoided include standing in line, being away from home, driving, crowds, being alone, sitting in a theater, being in a grocery store or shopping mall, etc.

Over time, a person may avoid new situations that appear similar to the original ones. Everyday activities may also be avoided, if they create internal experiences thought to lead to panic.

Internal Cues

Often the focus is inward, with attention to somatic conditions and fear of getting symptoms [diarrhea, dizziness] in the feared situation. (Hofmann and DiBartolo, 1997, p. 58; Carmin and Pollard, 1996, p. 46). Internal cues similar to the start of a panic attack may also be avoided, by avoiding activities that generate them, such as exercise, caffeine, scary movies, etc.

The person may be constantly alert for ways to feel safe, as well as people and situations to avoid. [Carmin and Pollard, 46]

21b. Comorbid Conditions

Look for the following as possible complications: (Carmin and Pollard, 1996, p. 47)

- Dependent, avoidant or histrionic personality, possibly as predisposing conditions.

- Chronic stress or life changes, as predisposing conditions.

- A chaotic family situation.

- Alcohol abuse, as the person attempts to self-medicate for the anxiety.

- Depression and sense of failure and defeat, especially after a history of failing to overcome the problem.

- Other anxiety disorders.

21c. Steps in Treating Agoraphobia

Treatment involves several steps:

- If the person’s agoraphobia is related to panic attacks, then the panic attacks must be treated first. Treatment follows essentially the same process as in treating a panic disorder [Section 17].

- Catalog both the set of feared situations, and the ways that the anxiety can be relieved.

- As much as possible, try to determine both the long-term conditions for the development of agoraphobia and the immediate precipitating conditions. Some of these may need to be addressed in order for the overall work to be effective. This is also a good time to provide information about aboraphobia, to de-mystify it for the patient and his/her family (Carmin and Pollard, 1996, pp. 59-60)

- Once the panic is at least partly under control, move on to treating the person’s avoidances [See Preparation for Exposure, below]

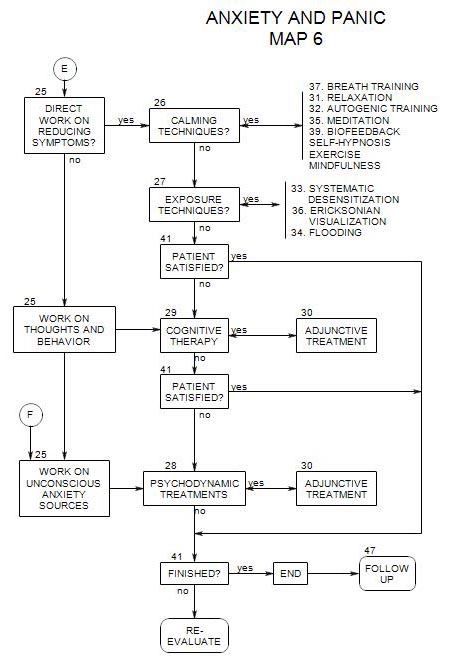

- After that, cognitive work is a possibility, to deal with irrational thinking, or psychodynamic treatment to look more closely at predisposing intrapsychic or interpersonal factors [see Section 25].

21d. Preparation for Exposure

Primary treatment consists in continued exposure to the feared situation, in a way that allows the person to stay in it or in contact with it. Simply returning as before is likely to lead to failure; the person needs new tools for coping mor effectively.

The idea of providing the person with ways of coping with the feared situations is typically considered part of the exposure technique. However, considering it a preliminary step points out that there are different ways of handling this aspect of treatment.

If possible, this is a time to enlist the sympathy and help of the person’s family and friends in the therapeutic process.

Calming techniques [Section 26] can be valuable in helping a person cope with the increased anxiety of overcoming his/her fear of going out.

Breathing training [Section 37] is generally considered to be an important part of treatment (Barlow, 1988, p. 472; Carmin and Pollard, 1996, pp. 60-61), because rapid breathing is both a symptom of anxiety and the source of other symptoms, such as dizziness.

Cognitive Therapy [Section 29] can be helpful in providing the patient techniques for re-examining his/her interpretations of the internal and external cues associated with the avoided situations

21e. Treating the Avoidances

Carmin and Pollard, 1996, pp. 64-68, recommend a two-part treatment, first exposing the patient to the internal cues that support the person’s avoidances, then going on to the situations and experiences avoided.

The internal cues vary from person to person. Some of these may already have been worked on, following the Treatment Steps above, if the person’s agoraphobia is related to panic attacks [see Section 17e]. The same exercises or similar ones will work for people whose agoraphobia is related to internal symptoms rather than to panic attacks.

You should already have collected a list of external avoidances [Section 3] that can be placed into an avoidance hierarchy and examined.

Exposure techniques [Section 27] can be used, to get the person to face the feared situations. All four combinations – imaginative or in vivo, combined with graduated or flooding, have been used in attempting to extinguish the avoidance behaviors. In addition, exposure can be therapist- controlled and monitored or self-paced.

According to Barlow (1988, pp. 407, 410) the most effective procedure is graduated, in vivo exposure that is self-paced by the patient. This involves developing of a hierarchy of tasks, based on their relative ability to generate the phobic reaction. Then therapist and patient work together on a plan that the patient carries out, exposing him/herself to situations successively higher on the hierarchy at a pace comfortable to him/her, and reporting back to the therapist on progress and difficulties [Barlow, 410, 414].

In addition to the above, exposure should be in an appropriate place. If the person has difficulty leaving home, exposure should have to do with leaving home, not just being out somewhere.

By contrast, prolonged in vivo exposure under the direction of a therapist may actually be detrimental [Barlow, p.414] because-

- it can produce a dependence on the therapist, making it more difficult for the person to continue exposure on his/her own.

- it is less conducive to feeling successful, unless self-paced.

- it is itself aversive, and may lead patients to drop out.

- there is a high dropout rate.

Patient Control

In contrast to the usual conditions for flooding, Barlow [412-413] recommends allowing a patient to leave a frightening situation before it becomes overwhelming, thus increasing his/her sense of control and the probability that he/she will return for more exposure in the future.

When the treatment has consisted in self-paced exposure to frightening situations in the form of homework between sessions, patients may be encouraged to continue even after the formal treatment is completed, and thereby continue to improve. [Barlow, 1988, pp. 411,414]

On the other hand, it is probably not a good idea to leave patients entirely on their own, as agoraphobia doesn’t improve without treatment, and unsupervised patients tend not to continue the treatment program [Barlow, 416]. For that reason, regular contact with the therapist is an important part of the treatment, even when patients are doing most of the work themselves.

21f. Adjunctive Treatment for Avoidance

Although cognitive therapy would appear to be helpful in dealing with avoidances, Barlow [425-427] cites evidence that it provides no real benefit and may actually interfere with improvement.

Couple or family therapy is an important part of treatment [Barlow, 460-465, 470] because-

- agoraphobic people are commonly dependent on others, either as a prior condition for the disorder or a consequence of it. Hence involvement of family and friends can be helpful when encouraging the person to overcome his/her fears.

- others in the family can support or undermine the treatment of any patient in therapy, especially if they feel excluded from the treatment plan. Their involvement and cooperation can be an important component in ensuring the success of the plan.

- the marital or family situation may itself be a major source of stress, leading to anxiety and panic attacks in one or more family members. Working with the family may relieve the background pressure on the identified patient.

- changes in a person during treatment can impact in other family members, usually in a positive way, sometimes negatively. If other family members are involved in the treatment, results are more likely to be positive for them and for the patient.

Benzodiazepines are typically not helpful, because-

- they reduce the very symptoms that the person needs to face and overcome.

- there is a possibility that the person will attribute any gains to the medication, rather than his/her own efforts, and not achieve a sense of effectiveness that is important for maintenance of improvements.

- there is a danger of physical dependency on the medications, along with a likelihood of rebound on withdrawal, especially if withdrawal is too rapid. Rebound of medication-related anxiety could lead to rebound of the agoraphobia.

- patients who attribute gains to the effect of medication also expect losses when the medication is discontinued. The expectation may make return of symptoms more likely, also undermining the effects of treatment [Barlow, 445].

Antidepressants [SSRI’s or tricyclics] may be helpful by-

- releasing the person from discouragement about continuing the exposure trials, so the real work can be carried out with less need for pressure from the therapist.

- allowing the person to appreciate any positive changes. [Barlow, 436]

21g. Further Avoidance Work

A primary condition for the termination of the therapeutic exposure phase of the work should be that the patient continues self-directed in vivo exposure to the feared situations, because this is very important both for holding on to gains and continuing to improve.

There may be some benefit to scheduling one or more follow-up sessions, to give the person an additional incentive to continue working.

21h. Continuing the Therapy After Termination of Avoidance Work

There may be real benefit to continuing with a different kind of treatment after the avoidances have been dealt with []. The choice of cognitive, psychodynamic, couple or family work can be made on the basis of the person’s issues and the therapist’s preferences.

Cognitive Therapy [Section 29]

This can be used to modify the person’s conscious thinking about his/her need to remain apart from the world, and the dangers it presents.

The person’s use of absolutes and other errors of thinking can be challenged.

A person’s dependency issues can be addressed directly through assertiveness training, thus possibly reducing one of the precipitators of agoraphobia [Barlow, 1988, p. 424]

Reframing can be used to suggest that the person’s real issue is not about leaving a safe environment for a dangerous outside world but rather about returning to one that is unsafe. This can raise the issue of the person’s interpersonal relationships, which can then be examined.

Issues for Psychodynamic Therapy [Section 28]

It may be helpful to pay special attention to several areas or themes in the context of psychodynamic therapy. Look for [Bennun, 181-182]-

- poorly resolved early dependency relationships.

- a current dependency relationship and fear of losing it, particularly if it is unsatisfactory.

- a recent death of a spouse or other person with whom a dependency relationship had existed, along with attachment to the memories of the lost person.

- issues about returning home rather than leaving it.

Family patterns (Bennun, 1986, p. 178): look for issues similar to the following:

- A parent is fearful of being alone and keeps the patient home as a companion.

- The person is afraid of something that may happen at home while he/she is away.

- The person fears for him/herself if he/she goes out. The perceived danger could be either external [e.g.: being attacked or robbed] or internal [e.g.: being tempted to use drugs or to be unfaithful to a partner.]

Look for internal conflicts about freedom and security (Wolfe, 2005, p. 269) where both poles of the conflict have both positive and negative aspects:

- Freedom suggests both autonomy and isolation.

- Security implies both being taken care of and being controlled.

Issues for Couple Therapy

A number of issues are possible. [Bennun, 180-81]

- Most agoraphobics are living with someone else, and the symptoms may reflect interpersonal issues, possibly dependency of the agoraphobic person on his/her partner or other family members.

- Agoraphobia may serve the unconscious needs of one or both partners, as when the non-symptomatic partner can take care of the agoraphobic one, and/or where the symptoms are serious enough that both partners believe they must remain together.

- The non-symptomatic partner may play a role in maintenance of the symptoms. This may not be evident until the symptomatic partner improves and the other one suddenly develops symptoms.

- At the same time, couple issues may exacerbate the symptoms of the identified patient, through his/her feelings of being helpless or trapped.